|

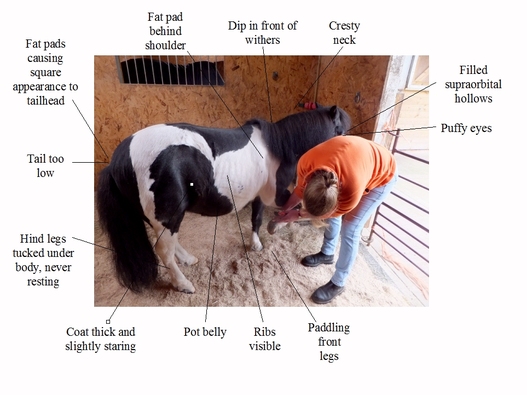

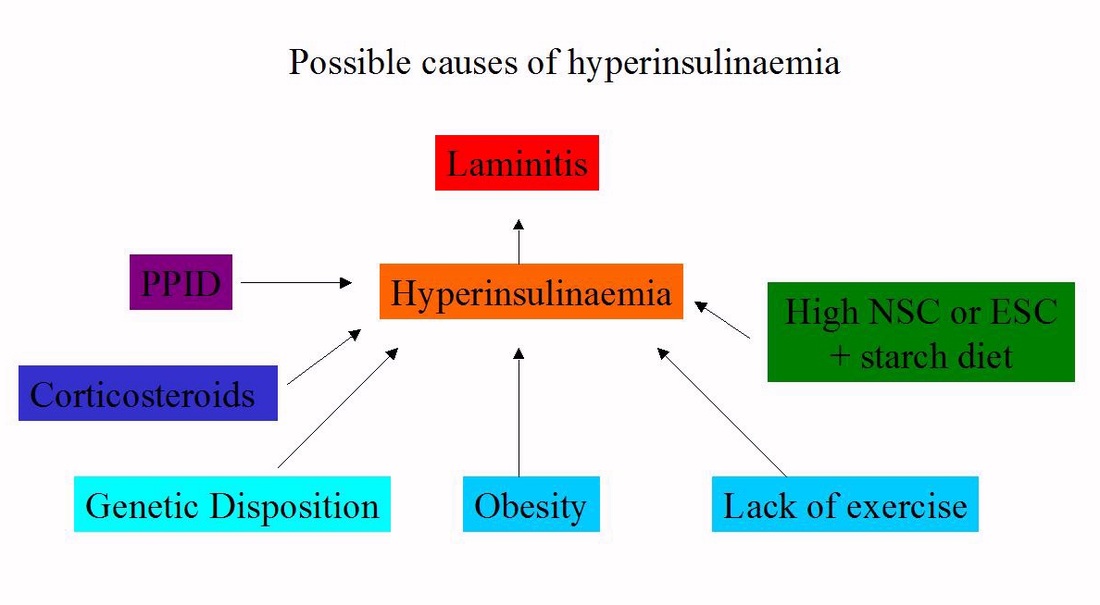

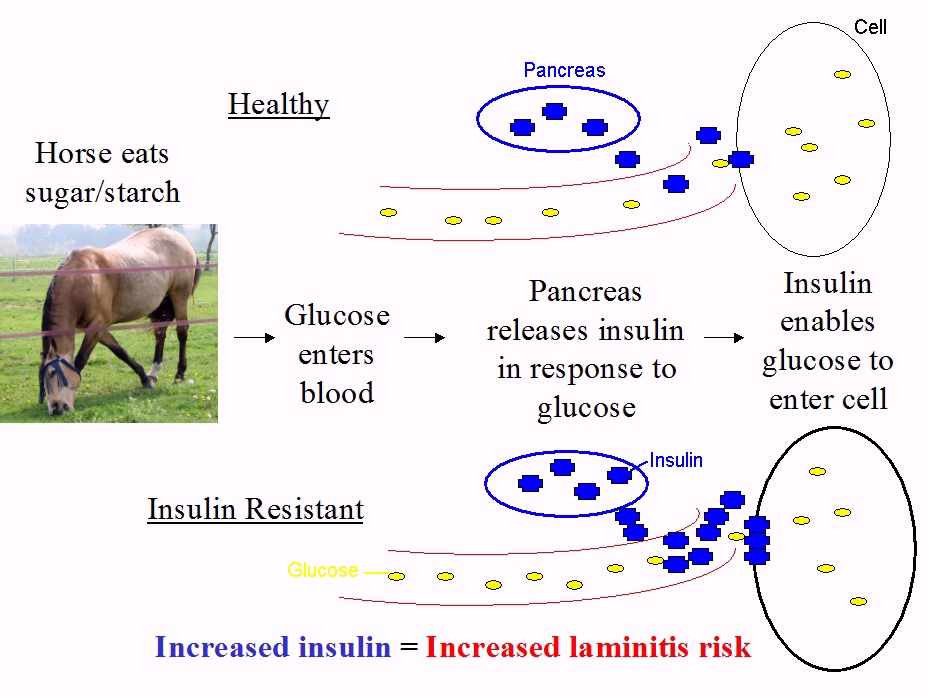

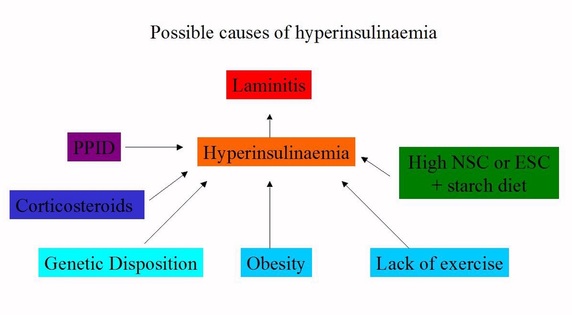

Has your horse got or are you worried about laminitis, EMS or PPID?

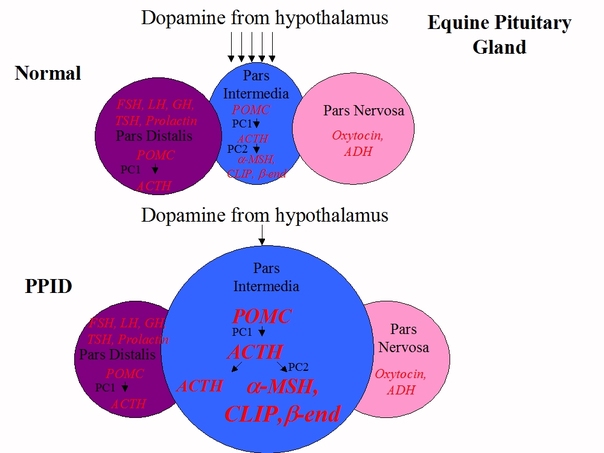

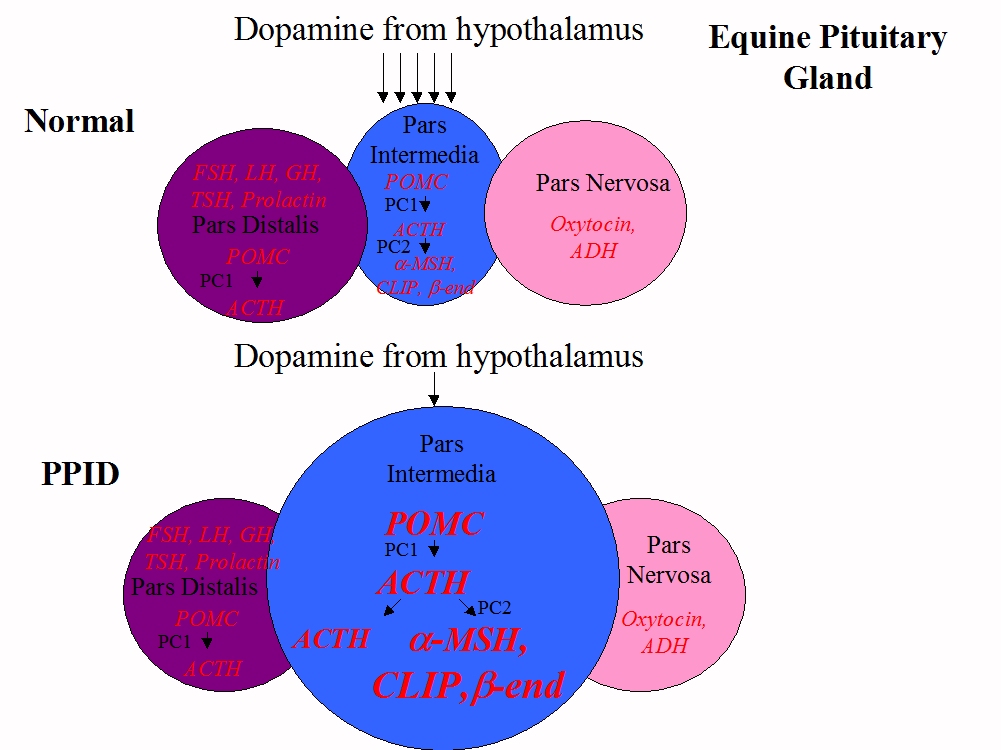

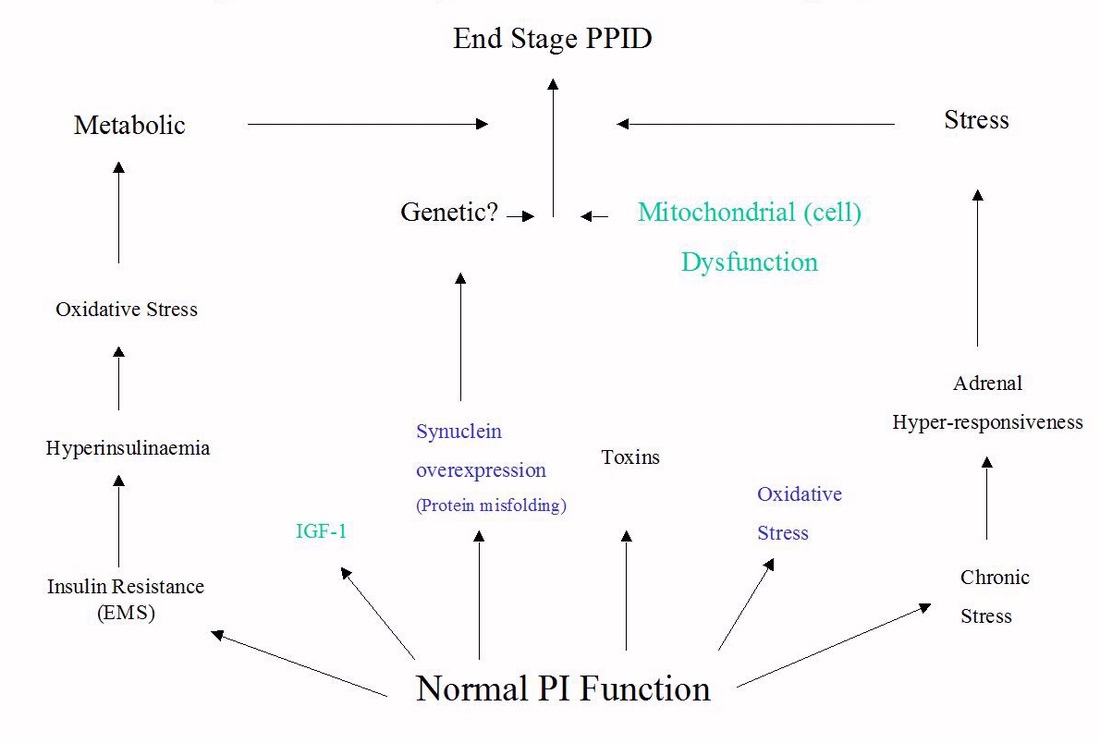

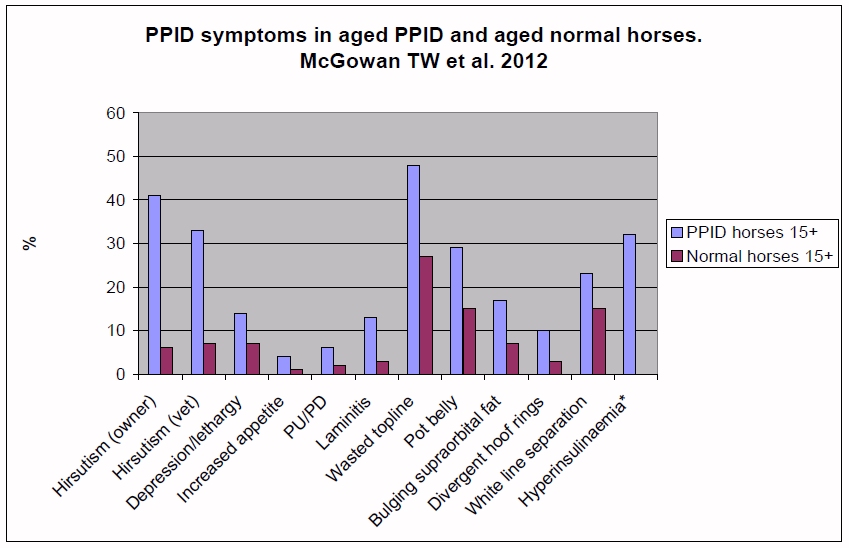

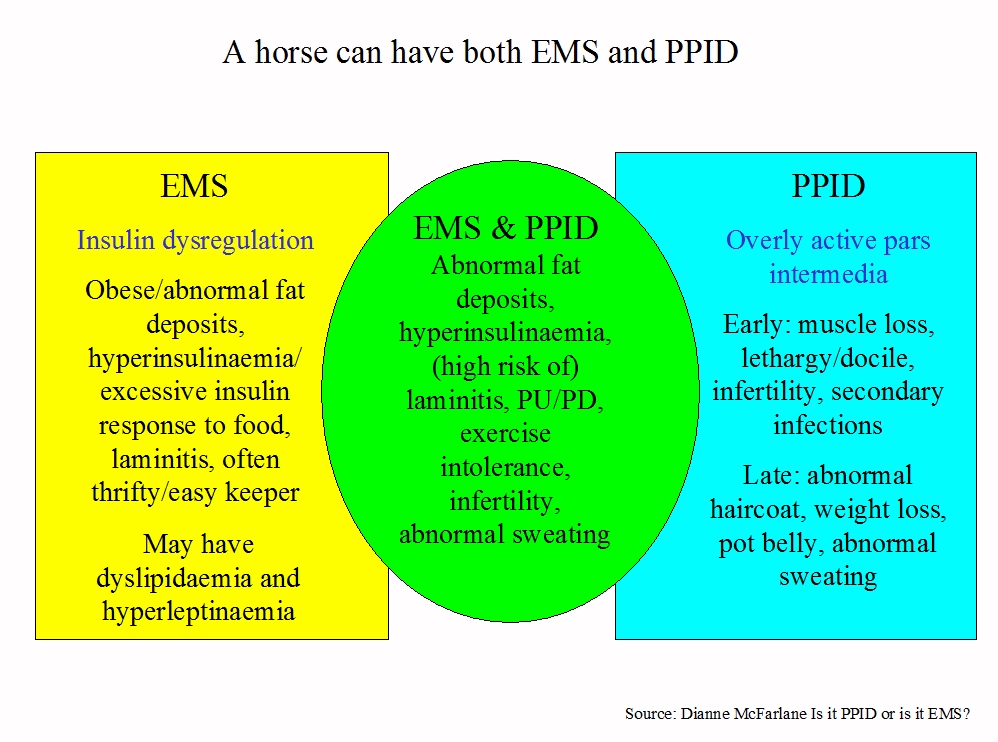

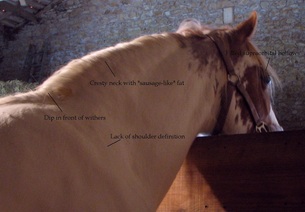

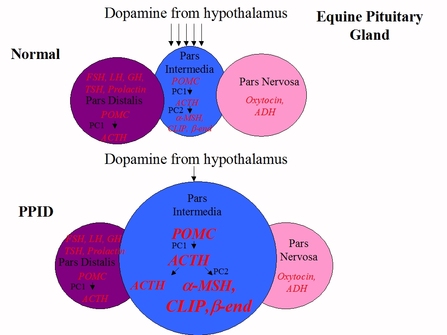

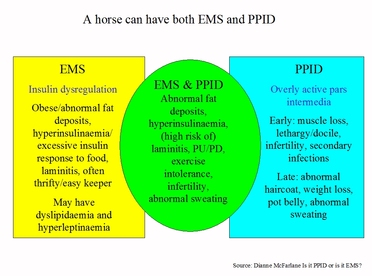

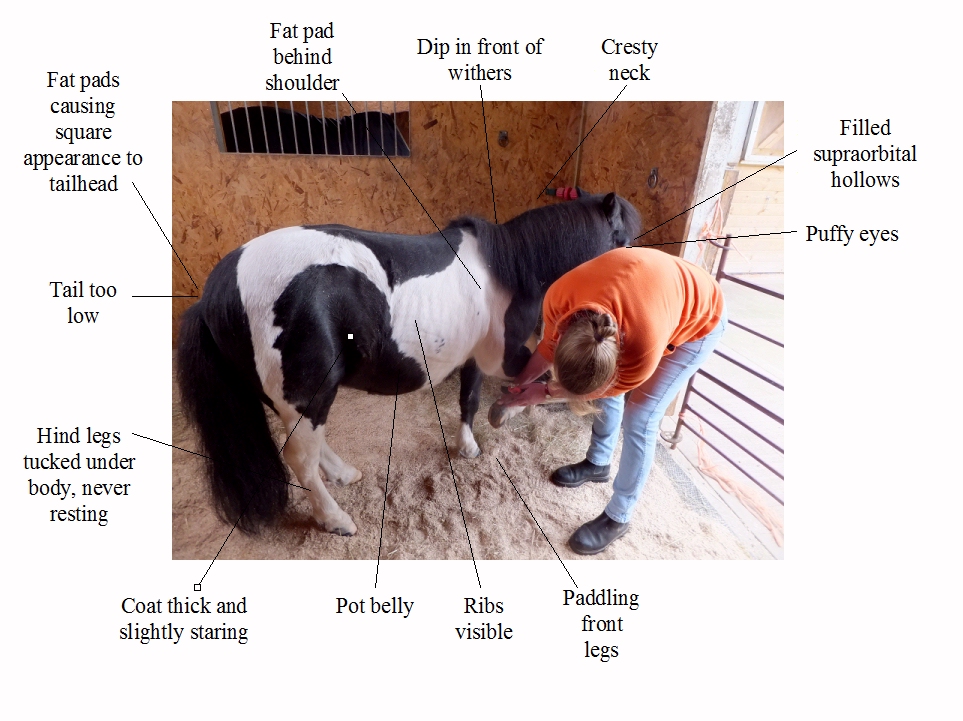

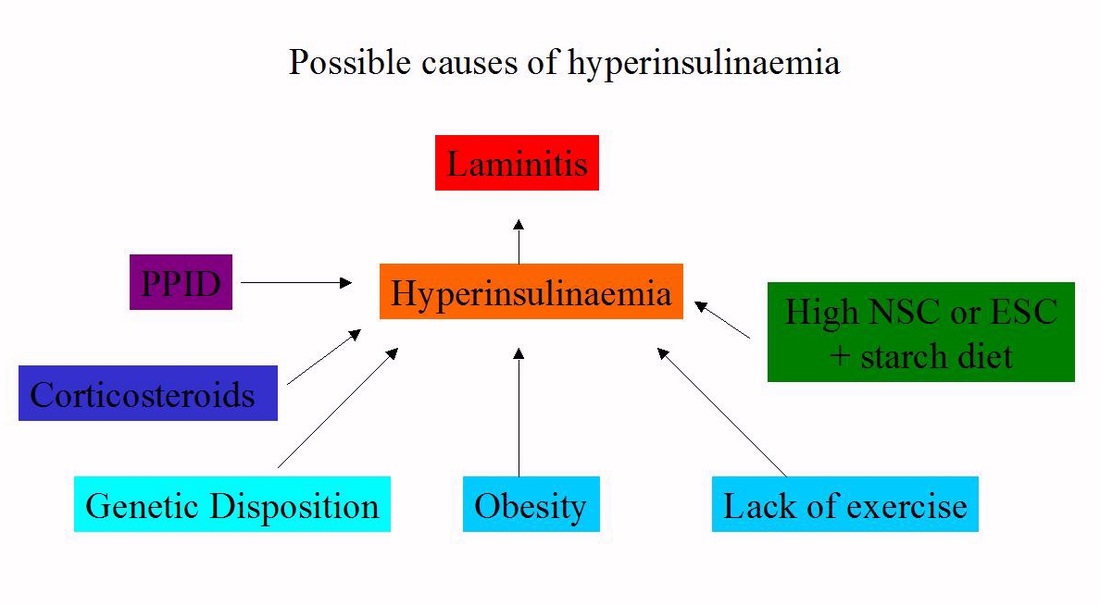

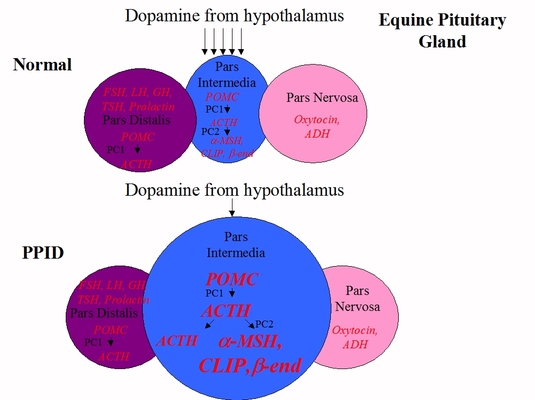

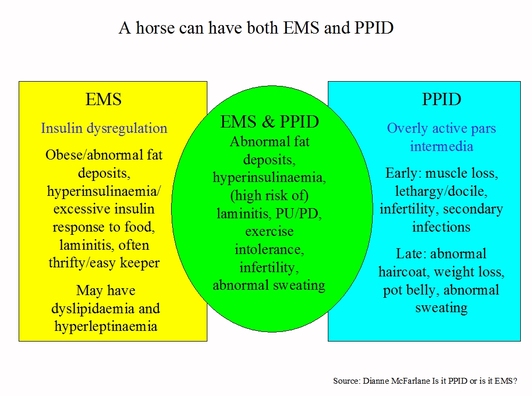

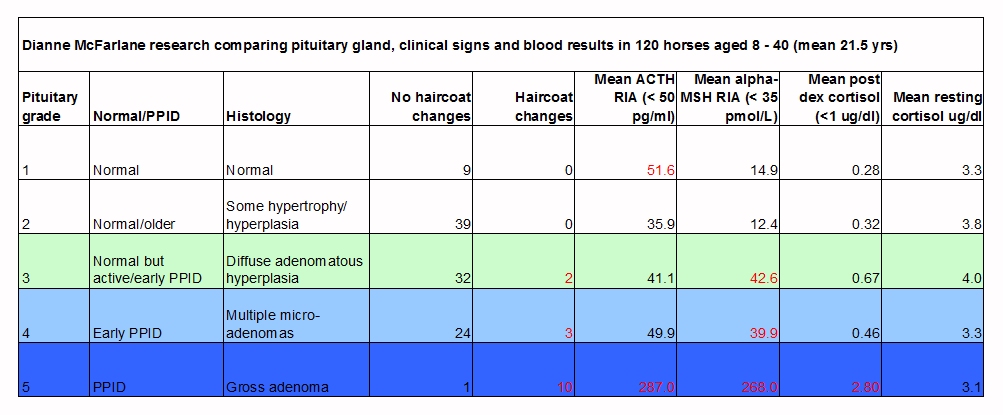

Check out The Laminitis Site's articles ... If he/she has laminitis, is correct emergency treatment in place? Do you know how to recognise laminitis, including sub-clinical laminitis? And how to prevent it? Laminitis, EMS and PPID Has the cause of the laminitis been correctly identified? Is it just Equine Metabolic Syndrome? Equine Metabolic Syndrome and insulin dysregulation Or could he/she also have PPID? Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction Video comparing PPID symptoms and normal agin |

|

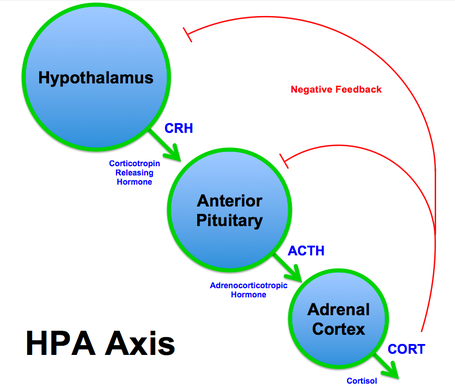

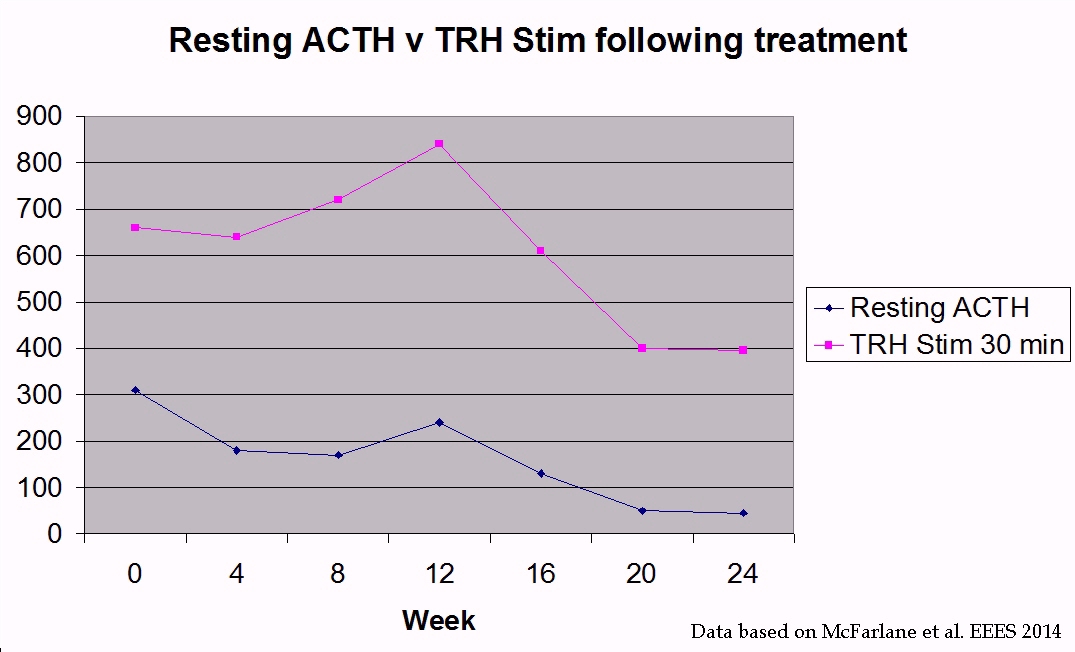

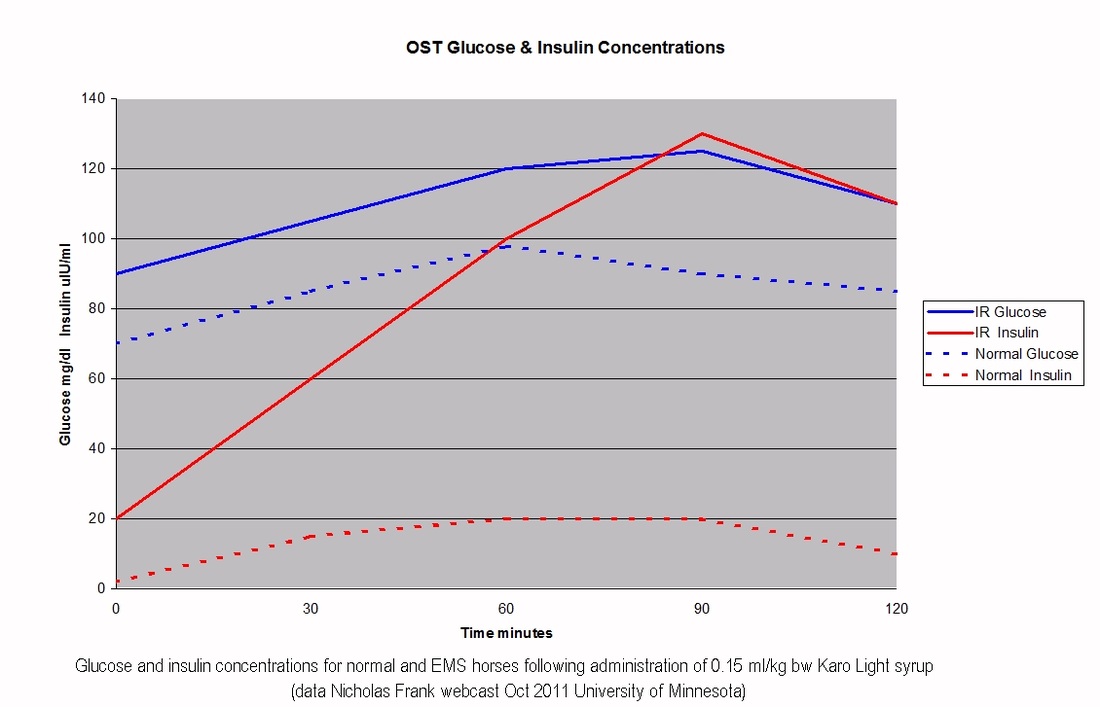

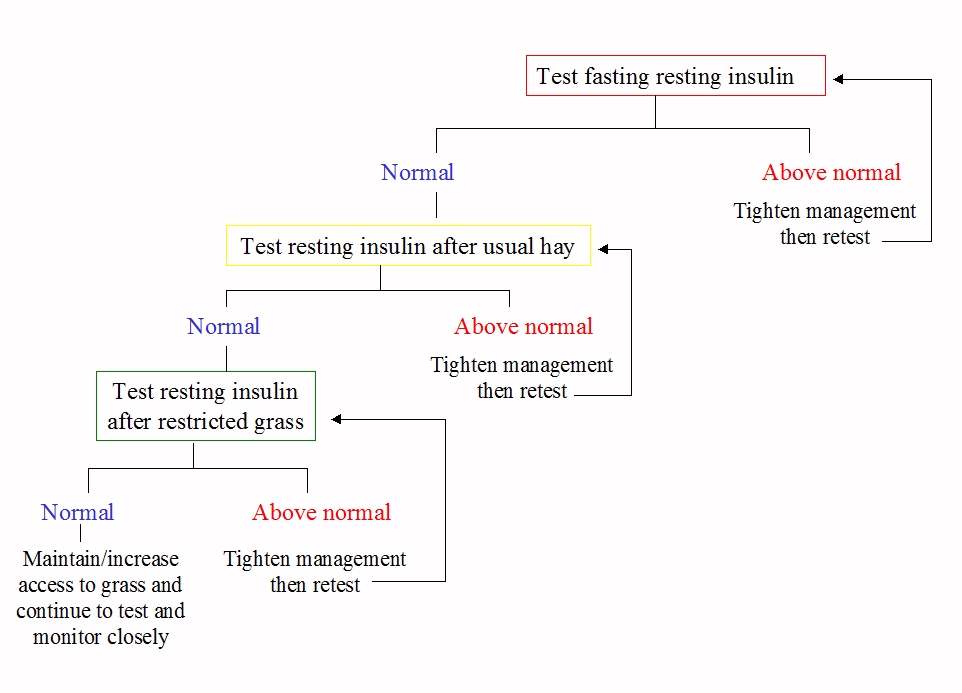

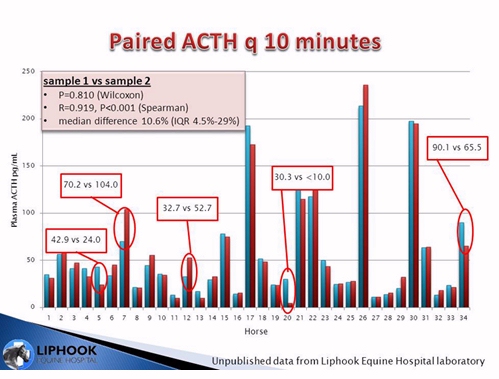

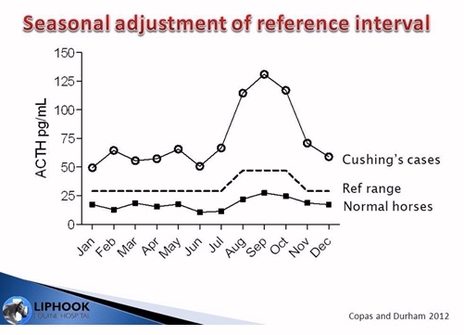

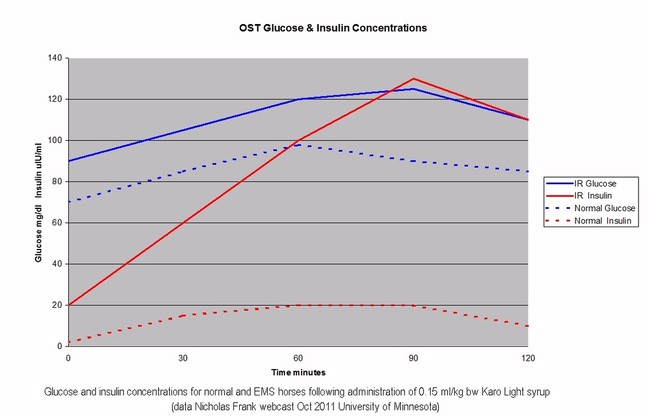

Has blood been tested for insulin and ACTH?

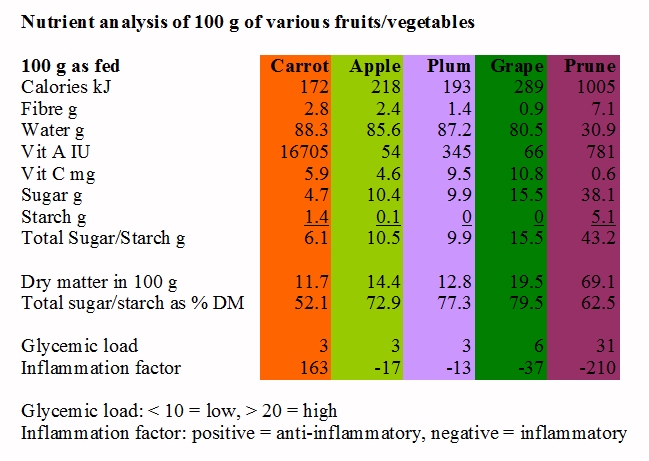

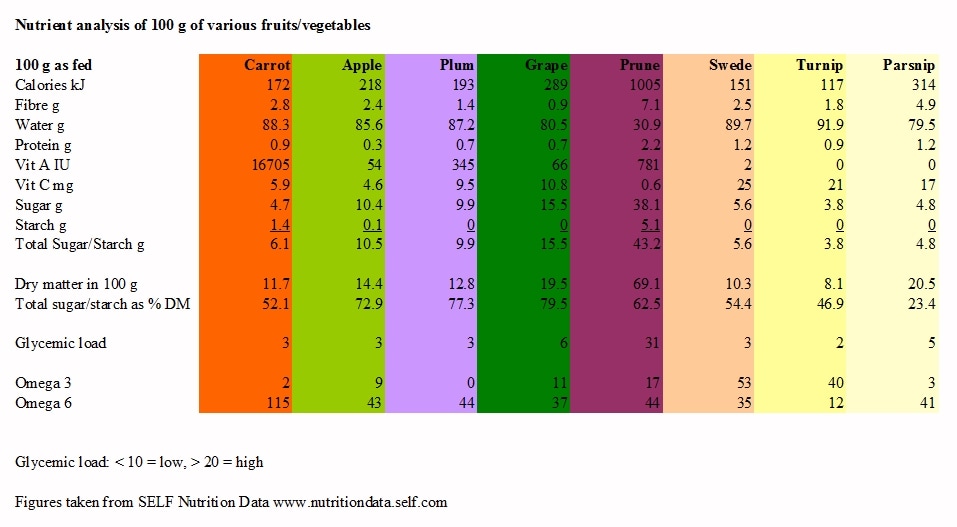

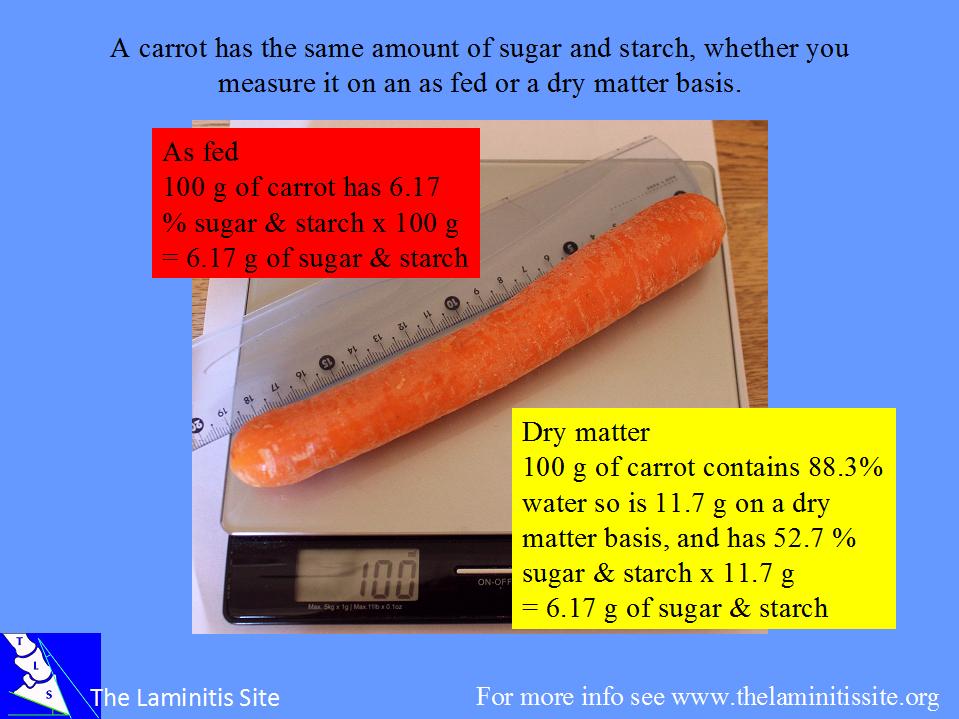

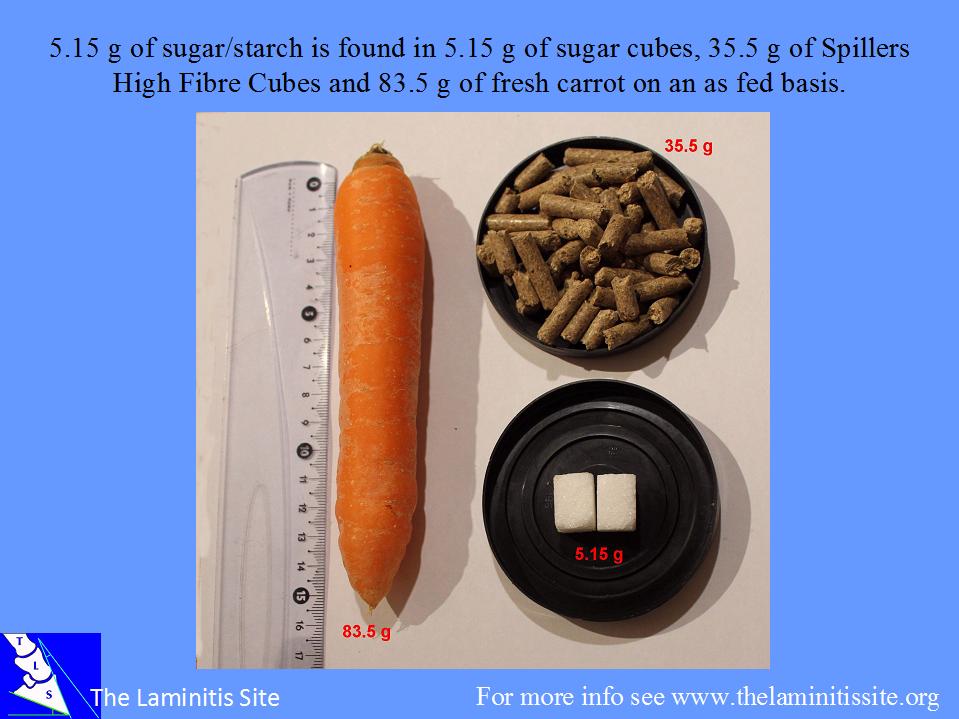

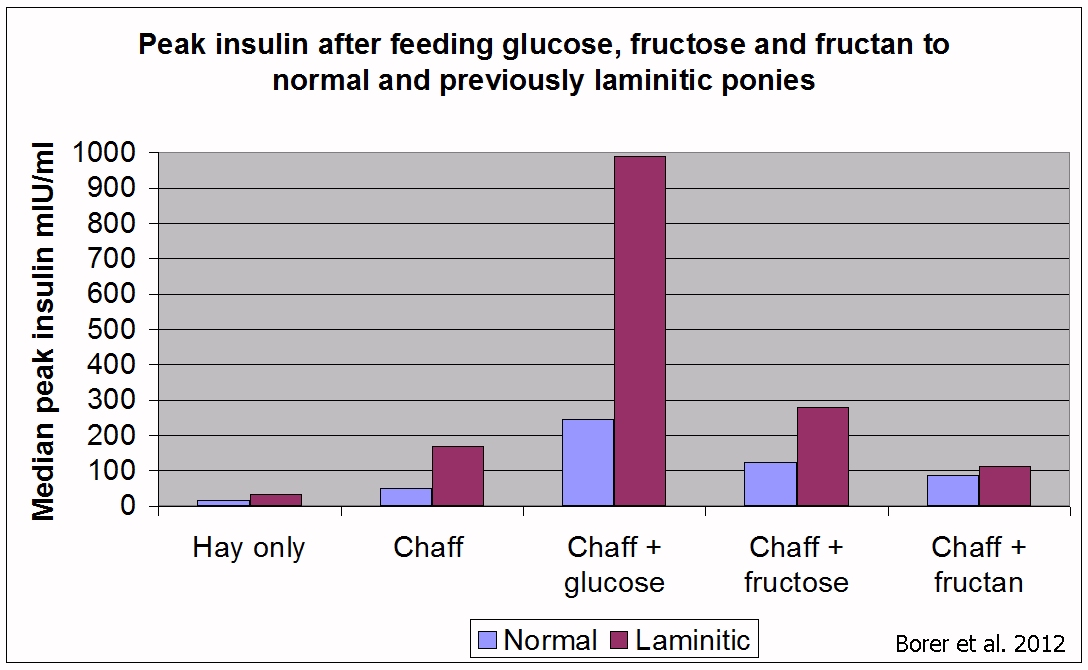

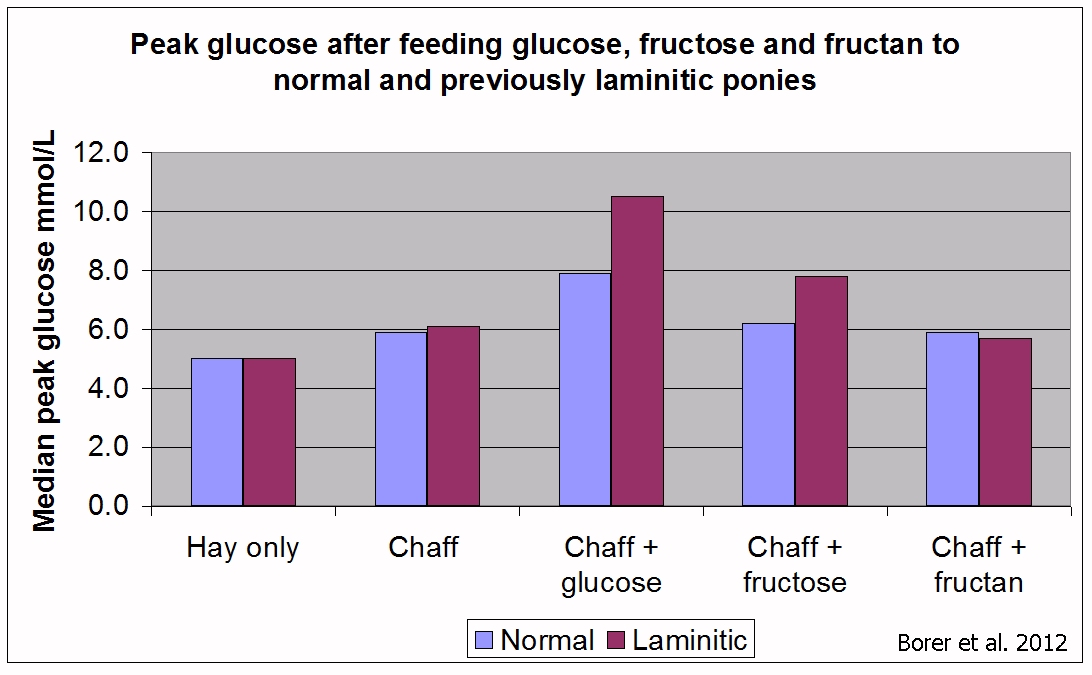

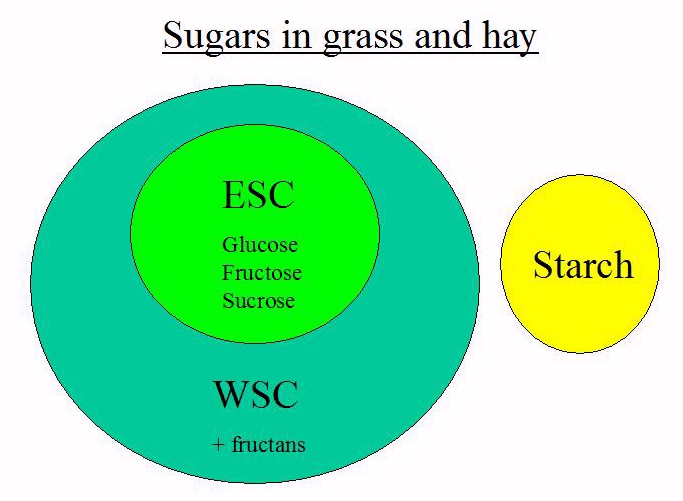

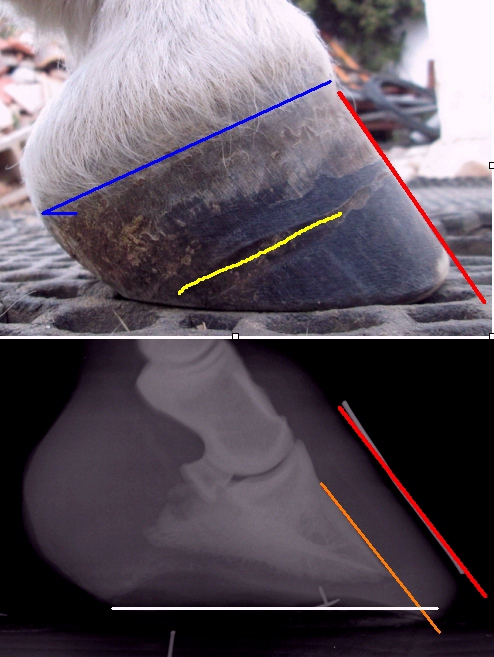

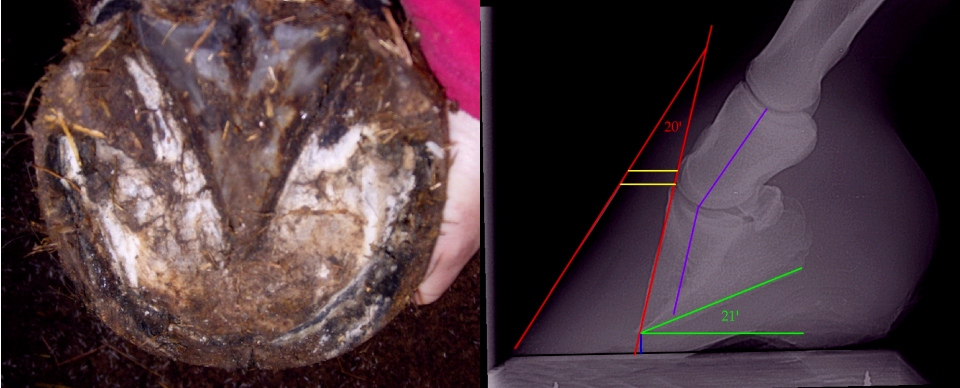

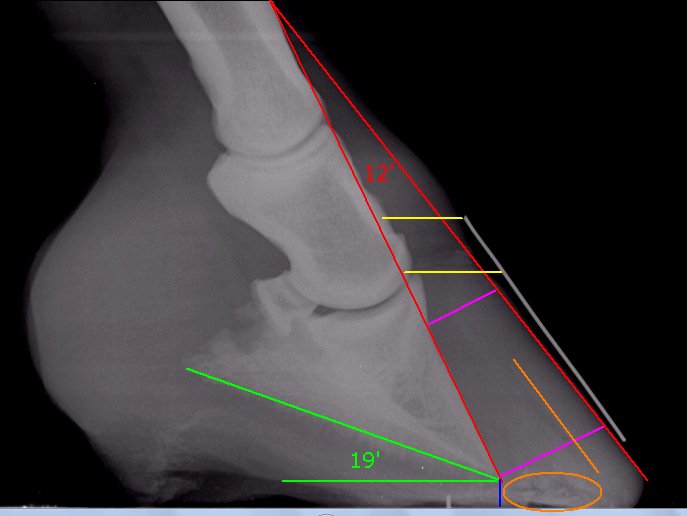

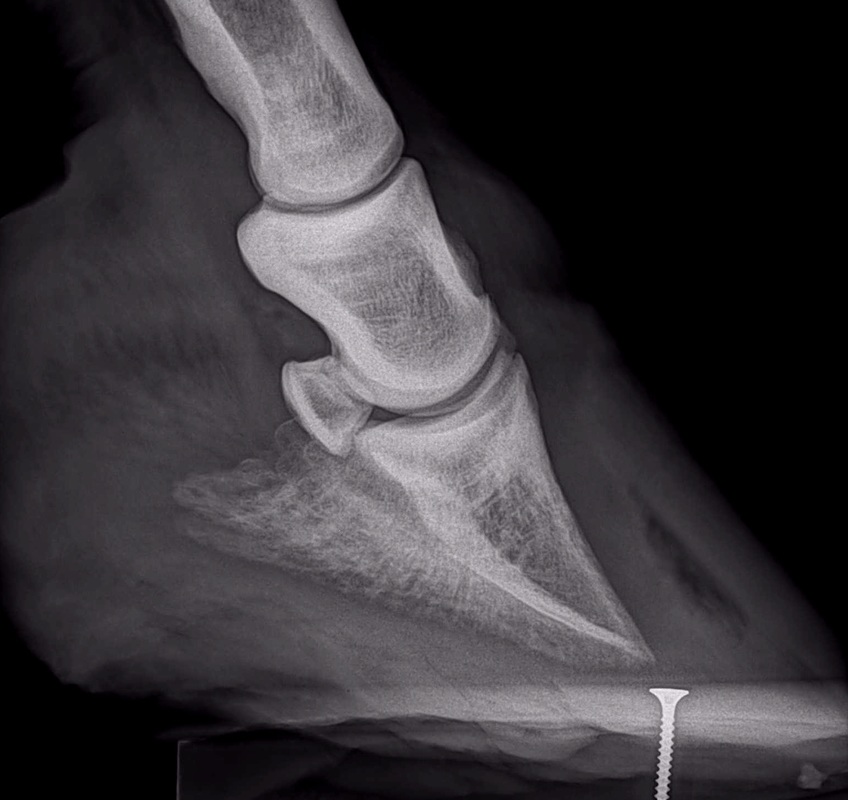

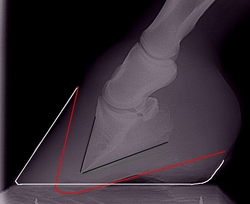

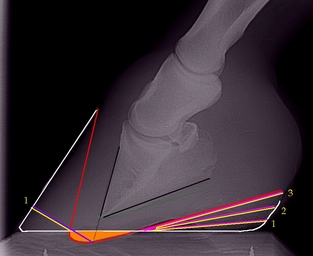

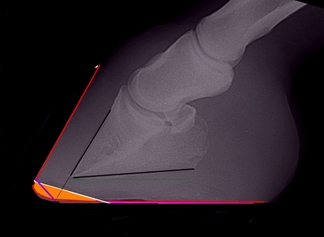

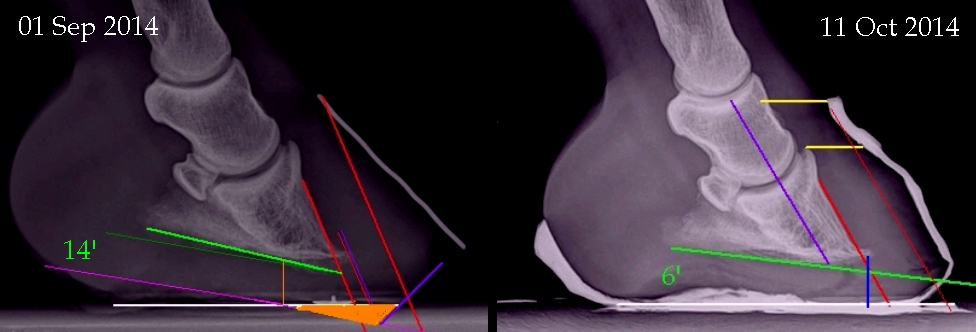

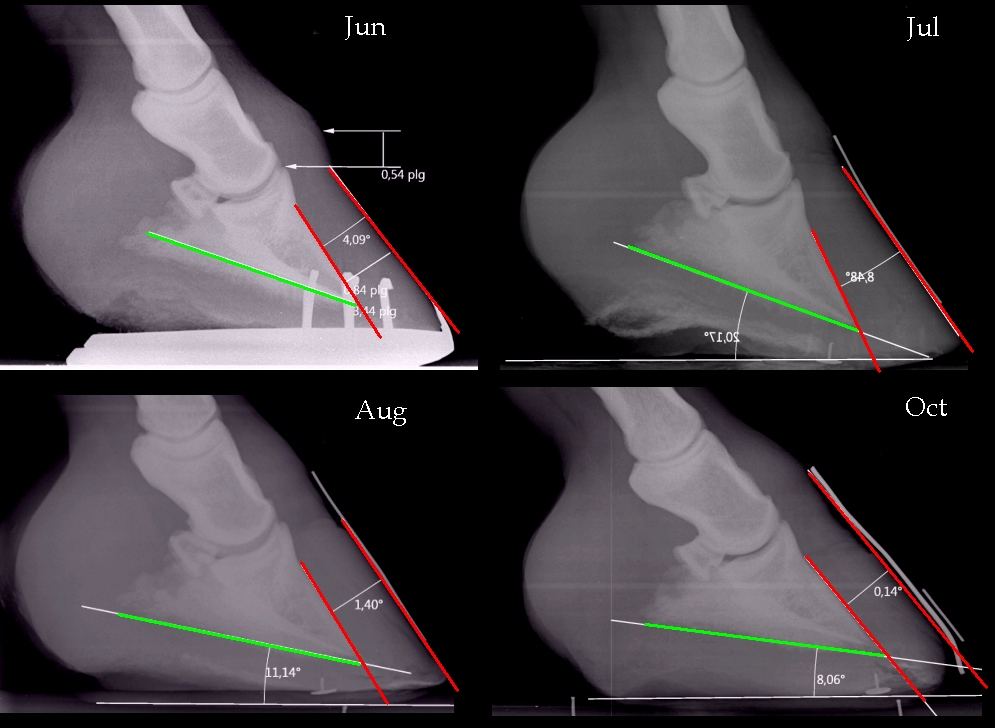

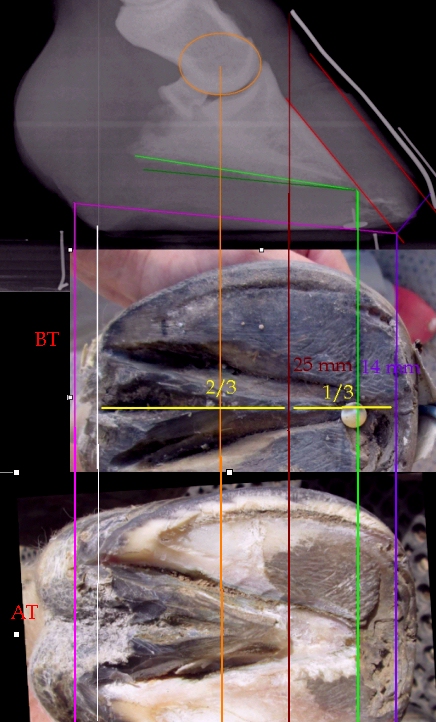

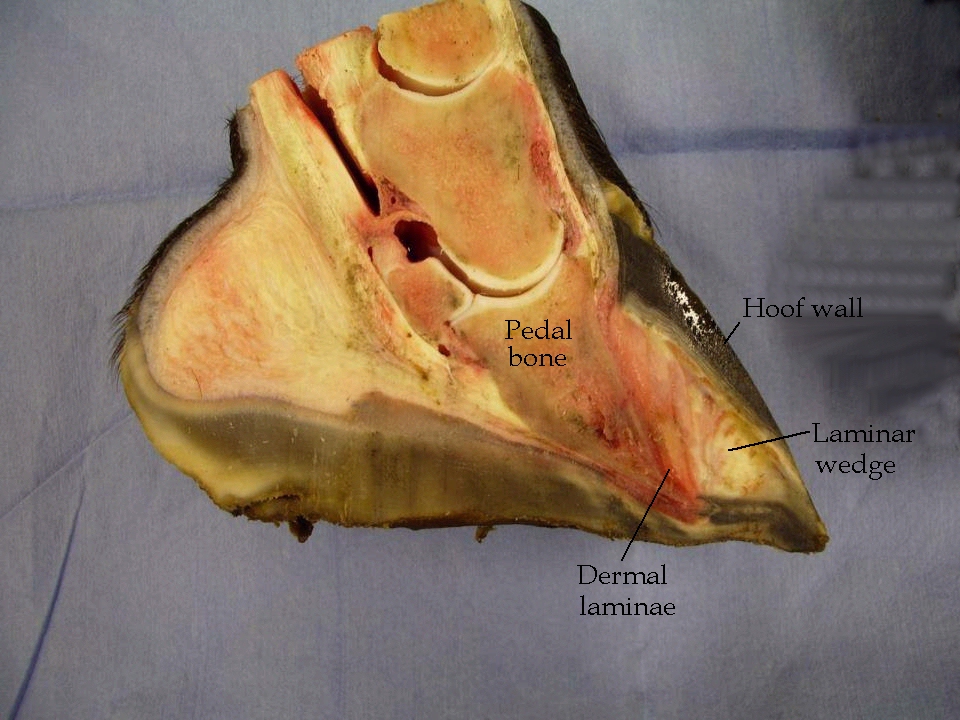

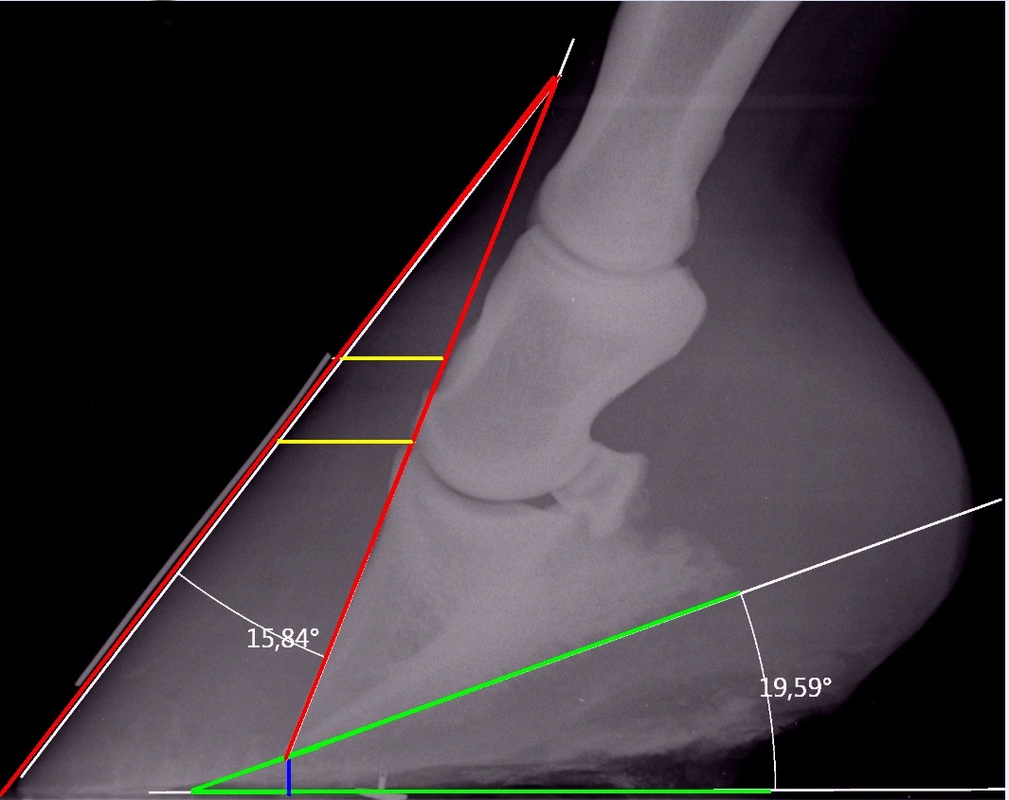

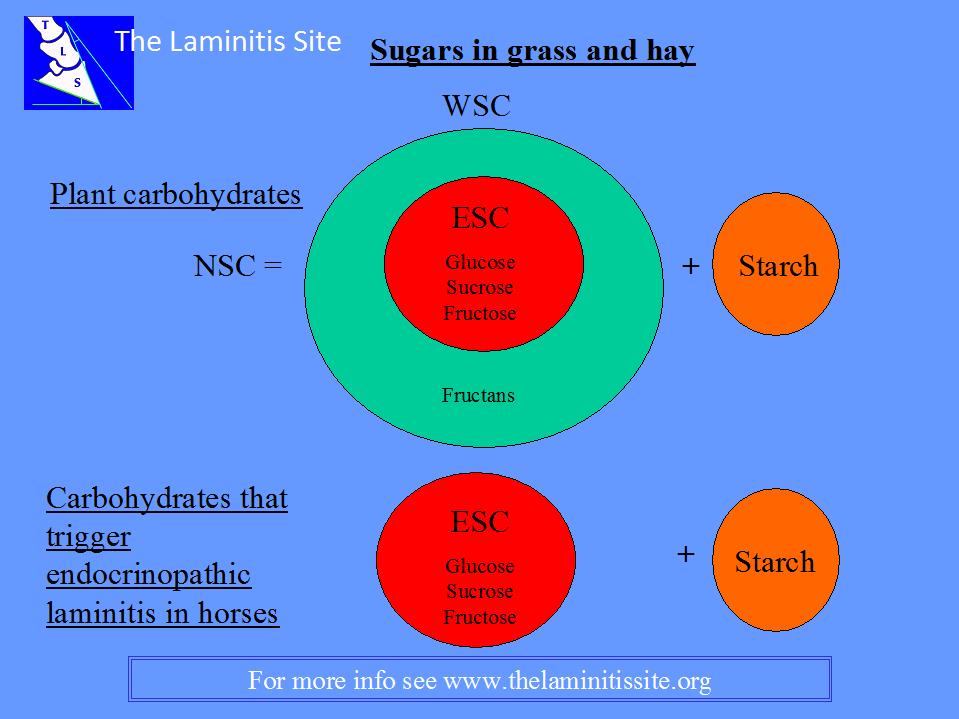

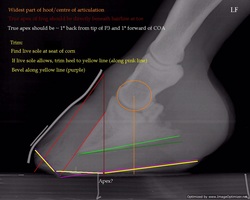

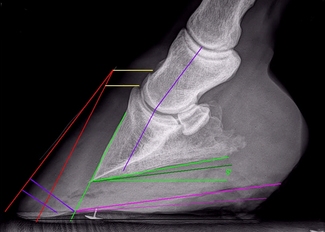

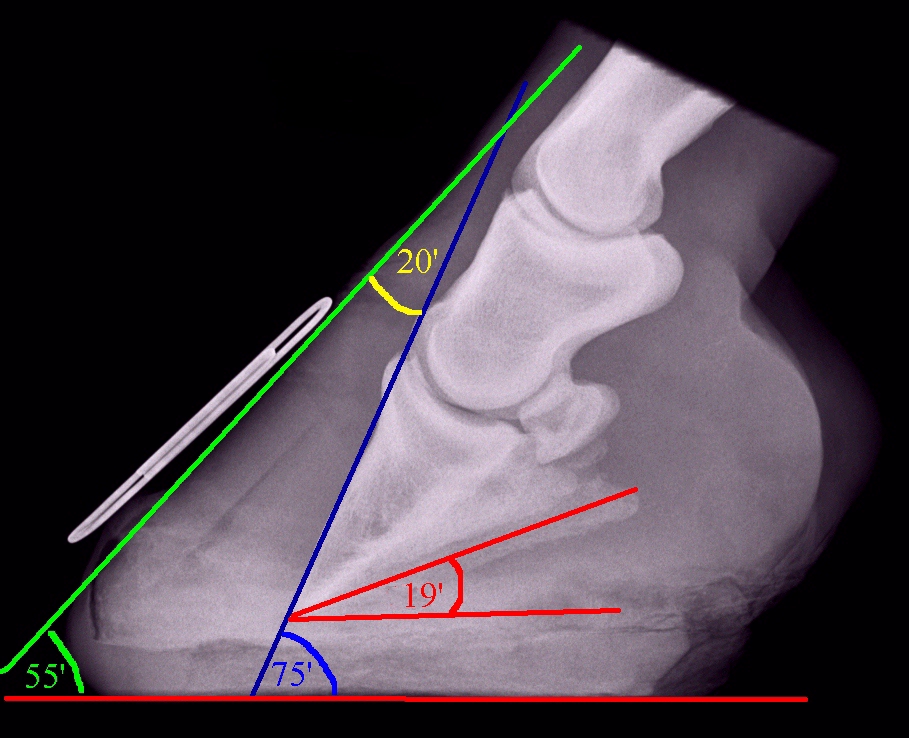

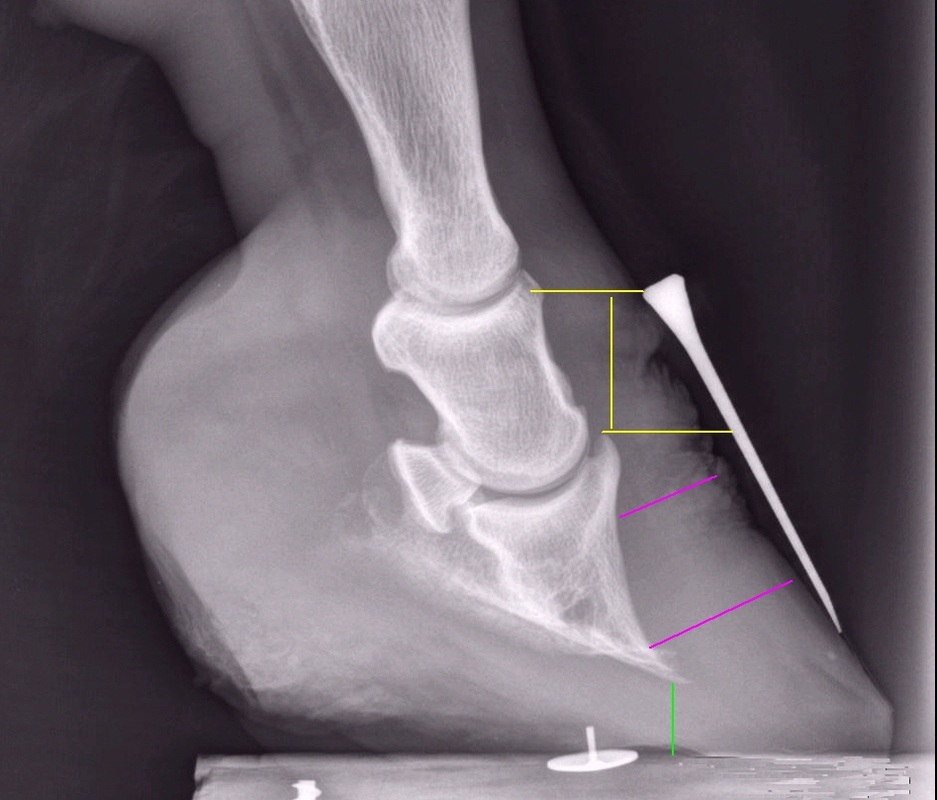

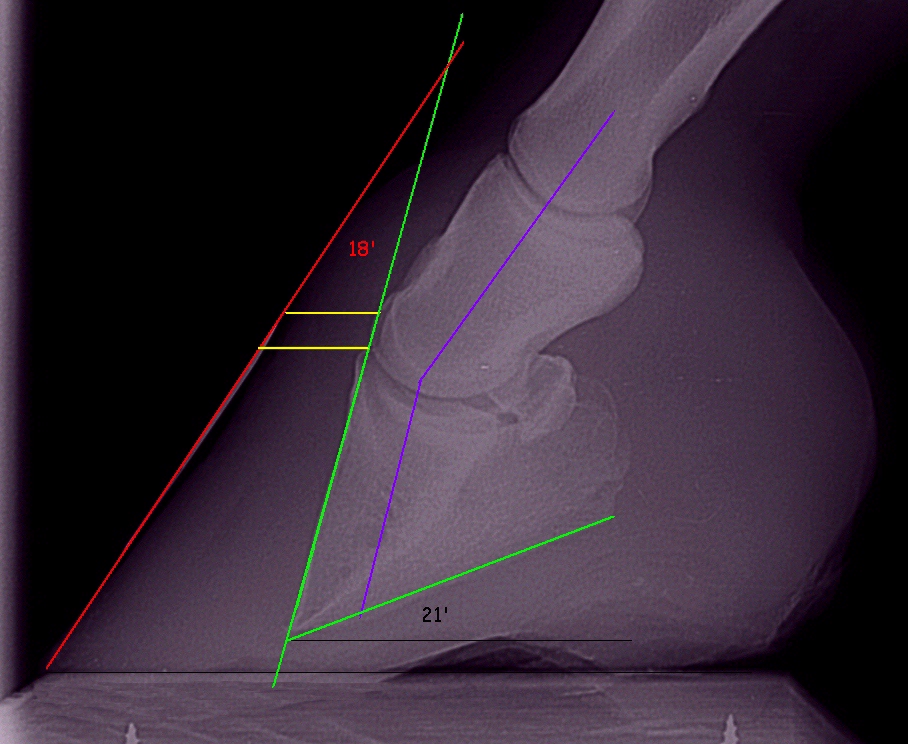

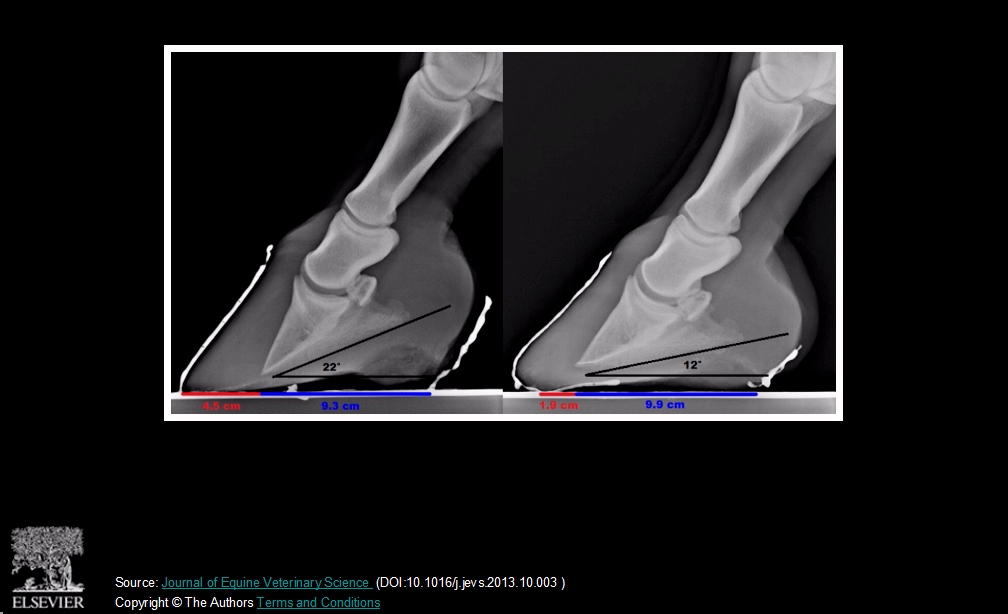

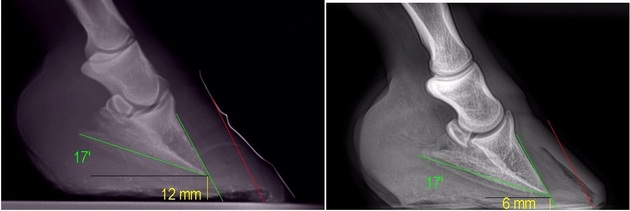

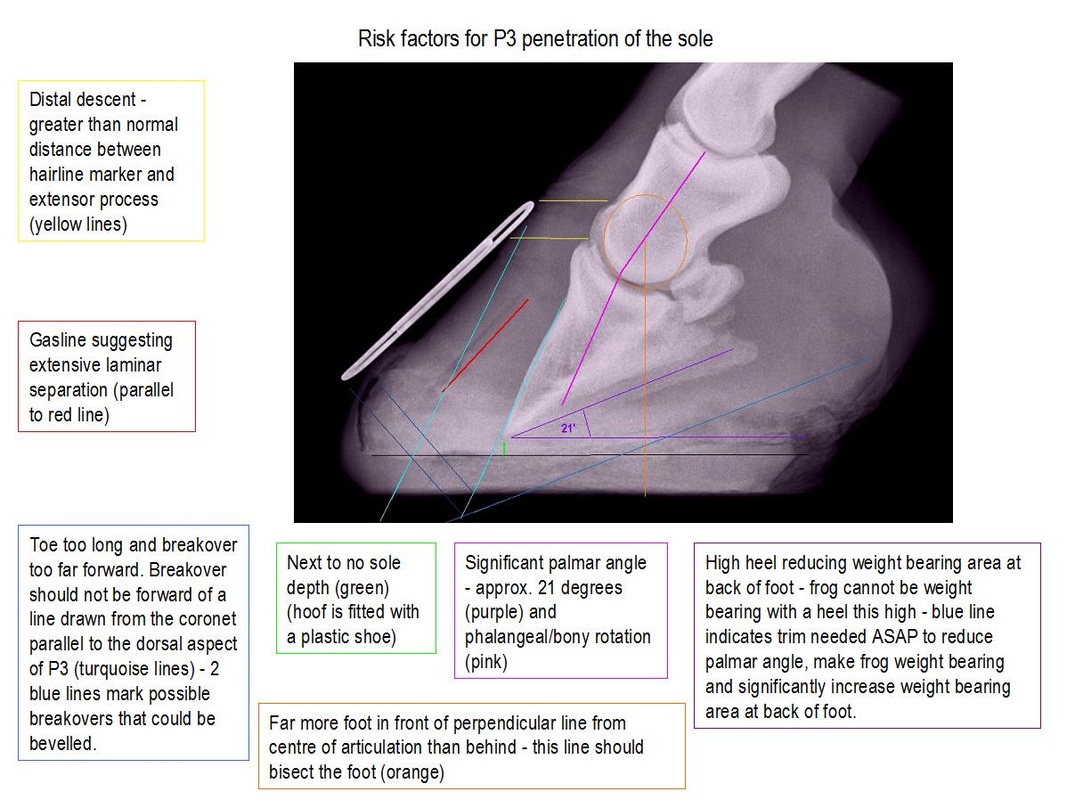

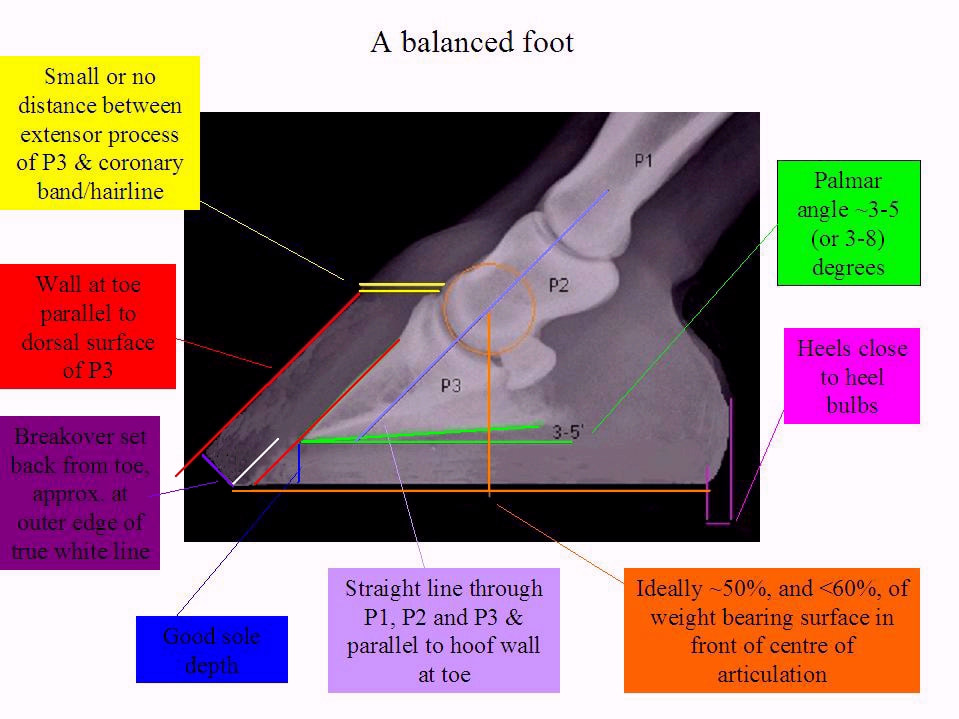

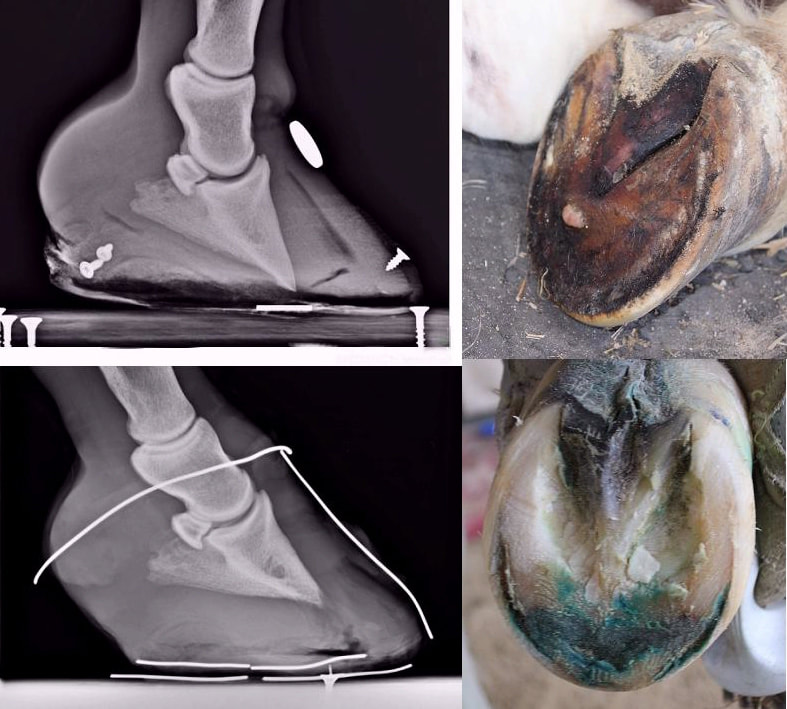

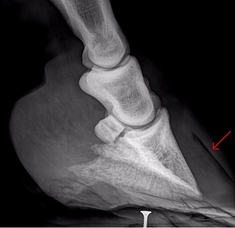

Testing Insulin Is it PPID or is it EMS? Are the feet well supported? Have x-rays been taken and any rotation corrected with a realigning trim? Laminitis and the Feet FAQ: Rehabilitating the feet after laminitis Is the diet low in sugar and starch but providing adequate nutrients and fibre? Diet for horses with laminitis/EMS/PPID |

Body Condition Scoring Video

Diet for weight loss

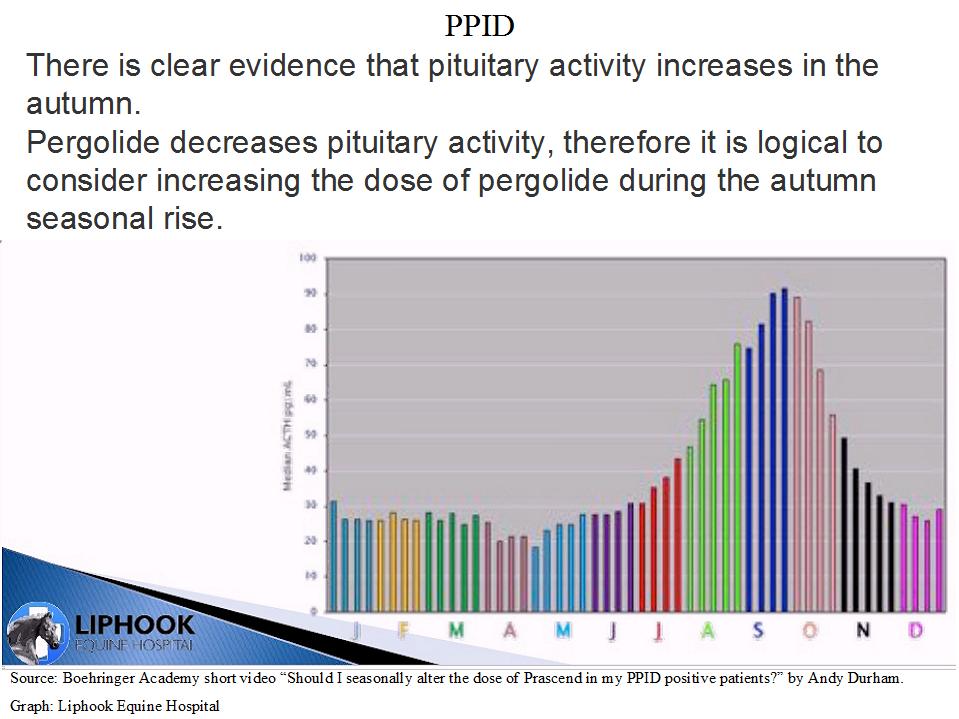

If he/she does have PPID, has pergolide treatment been started?

Starting Pergolide/Prascend

Are you wondering whether a supplement could help?

There are no magic potions!

Are you confused about how much your horse should be moving following laminitis?

Movement - good or bad?

Want some suggestions for managing a horse with EMS, particularly if hay/grazing need to be restricted?

Management Strategies for EMS/insulin dysregulation

Need some inspiration? Here are a few of the horses that have recovered from laminitis following TLS's protocol:

Casareño's recovery

Nutmeg's TLS Rehab

Sorrel

Need support or more information? Become a Friend of The Laminitis Site and access the Friends of The Laminitis Site 1 discussion/support group on Facebook. If you are in North America, consider joining the ECIR Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed