Managing Horses with PPID with Dr Marian Little and Dr Dianne McFarlane

on 27 February 2014

Sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Background:

Dr McFarlane (M) – 12 years studying PPID, understanding causes, diagnosis and treatment protocol. Wanted to know how best to care for older horses.

Dr Little (L) – vet with BI since 2007, lost 2 horses to PPID.

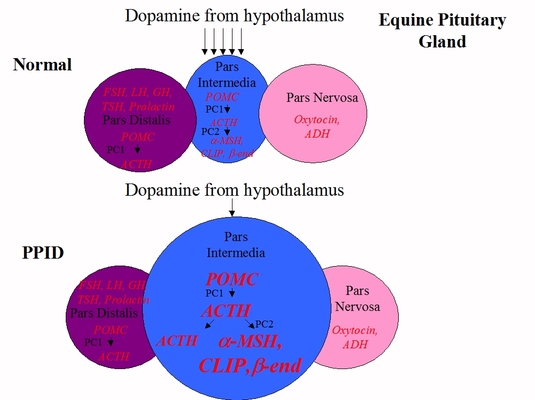

L: PPID – most common endocrine disorder of aging horses, prevalence 15-30 % of horses over 15, this is probably an under-estimate. Chronic degeneration of dopamine secreting neurons leads to loss of dopamine controlling effect to pituitary, which leads to enlargement of the intermediate lobe and increased secretion of hormones.

Early clinical signs – changes in behaviour, loss of topline, secondary infections, haircoat changes, late shedding.

Later signs: “woolly mammoth”, leaner body condition. Some get PU/PD, sweating abnormalities, abnormal fat deposits, laminitis related to insulin.

TLS: laminitis, especially in the autumn, is often the first sign of PPID that is noticed.

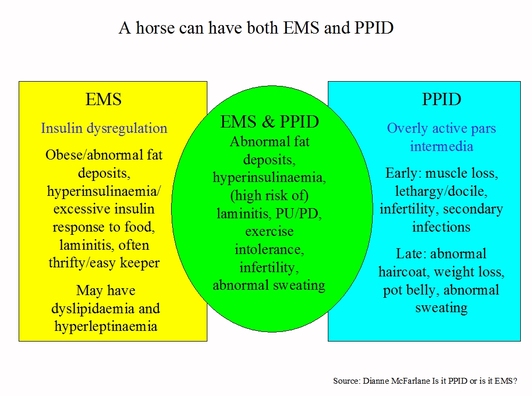

Q. What’s the difference between IR and PPID?

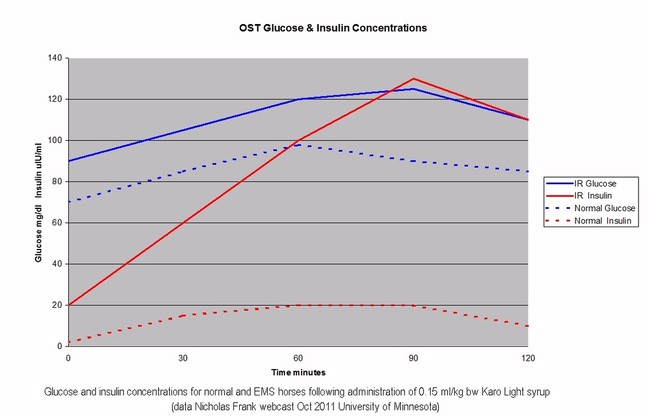

M: 1/3-1/2 horses with PPID will also have dysregulation of insulin, i.e. insulin resistance. They will have high insulin concentrations (tests: resting insulin or Oral Sugar Test), and high insulin causes laminitis, so these horses are at high risk of laminitis. 1/2-2/3 of horses with PPID are not at risk of laminitis. Both conditions can happen together – insulin dysregulation (EMS) and PPID in the same horse, with these horses we need to be very cautious of how they are fed, particularly whether they have grass, as there is a high risk of laminitis. But if insulin is normal PPID horses can have grass and as these horses are often thinner, they are likely to need feeding to maintain weight rather than lose weight

Q. How effective is Pergolide as a treatment of PPID, can it be used on a seasonal basis?

L: In the 1980s research suggested horses with PPID have an 8 fold decrease in dopamine in the pituitary gland, since then pergolide has been considered the treatment of choice. There are over 25 published references from the past 30 years describing pergolide’s usefulness in improving clinical signs and test results.

Most recent being the 2009 study for FDA approval of Prascend - 76% of 113 horses with PPID were deemed treatment successes http://thelaminitissite.myfastforum.org/about14.html.

Most common side effect is inappetence - 30% of horses in Prascend study had loss of appetite, only 2 required dose reduction and both returned to a normal dose within the first month.

Recommended starting dose is 2 mg/kg bodyweight so 1 mg/1000 lbs, horses should be monitored and dose adjusted appropriately to control both clinical signs and test results.

No data on the intermittent use of pergolide, but given knowledge of Prascend and the disease, she would be skeptical we can just treat in the autumn and expect adequate control throughout the rest of the year.

TLS: From the Equine Endocrinology Group’s Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of PPID: It is therefore recommended that PRASCEND be introduced gradually by giving partial doses for the first four days or by administering half the dose morning and evening.

http://sites.tufts.edu/equineendogroup/files/2013/11/EEG-recommendations_-downloadable-final.pdf

Q. How does Pergolide work?

M: Pergolide is a dopamine agonist – acts similar to dopamine – PPID is the result of a loss of dopamine in the pituitary, pergolide replaces lost dopamine and reduces hormones being produced, when hormones return to normal concentration, clinical signs resolve.

Q. Pergolide was banned from human market because risk of heart problems, is it ok for horses?

L: Some humans taking ~ 3 mg pergolide for Parkinson’s disease developed fibrosis of heart valves. This is not an issue in horses, likely due to differences in dosing with regard to dose in proportion to body weight, also there are differences in heart muscle receptors that are stimulated and some other minor differences between humans and horses. In pergolide research carried out in horses to date there have been no issues noted with cardiac abnormalities. The FDA 6 month Prascend target animal safety study evaluated 32 horses at elevated doses of Prascend, no cardiac abnormalities were observed clinically or at necropsy.

Q. Are minis/ponies dosed the same as horses?

L: 2 mcg/kg bodyweight so ~ 0.5 mg for a pony is the recommended starting dose, watch for inappetance. Ponies can be worse in terms of clinical signs, progression of disease and insulin dysregulation than horses.

http://www.noahcompendium.co.uk/?id=-447753

Q. 25 year old gelding diagnosed with PPID last year because he was sweating when other horses weren’t, being treated with Prascend. His winter coat is longer than other horses but not excessively long and it does shed out almost completely. What signs would indicate that his dose needs to be increased?

M: Sweating excessively can be an early sign of PPID and may happen before haircoat abnormalities. Diagnosis of PPID should take into account clinical signs and blood tests, worsening of either can indicate that the dose of Prascend needs to be increased.

Q. What % of ponies have PPID/EMS, and how many are diagnosed at a young age?

M: By the time they are in their 30s, prevelence of PPID in ponies may be 50% (guess!). Ponies are more at risk of insulin dysregulation, particularly if fat – they are bred to be thrifty – therefore at risk of having both conditions, need to watch feet because of risk of laminitis.

Q. Horse had elevated cortisol levels, started on Prascend, when should he be retested?

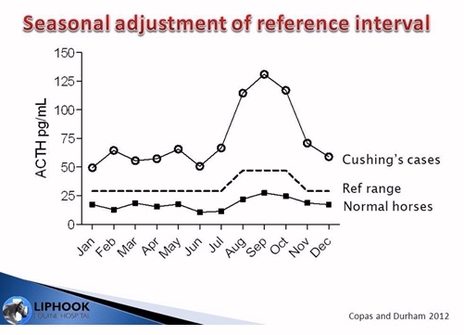

L: By cortisol presumably this means post-DST cortisol, as resting cortisol is not recommended as a diagnostic test. Retest 30 days after starting treatment with Prascend, then every 6 months, with one test in autumn seasonal rise.

In the USA the upper end of the dose range is 4 mcg/kg (10 mcg/kg in the UK). Some members of the Equine Endocrinology Group recommend a higher, more flexible dose before considering dual treatment but this is an extra label recommendation (i.e. not recommended on the Prascend data sheet).

With an advanced case, it may not be possible to get hormones into the normal reference range even though clinical signs are responding well – either try raising the dose to see if test results will come down into the normal range or stick with the dose as long as it is controlling clinical signs.

In earlier/milder cases best to adapt dose to try to get both hormones within normal range and achieve improvement in clinical signs.

Best not to overly focus on reaching a particular target for blood results, but focus on achieving a significant improvement in clinical signs and when possible a significant improvement in test results as well.

TLS strongly advises against using the dexamethasone suppression test.

http://sites.tufts.edu/equineendogroup/files/2013/11/EEG-recommendations_-downloadable-final.pdf

Q. Will a horse with PPID need Prascend for rest of its life?

M: Yes. At the moment we tend to diagnose horses once they have fairly significant disease. Perhaps in future if recognised early and we understand more about dopaminergic neurons we may be able to change this. But once dopamine neurons have been lost we need to keep replacing dopamine for life. Dr Schott has found that many horses do not need increased doses but can be maintained on a consistent dose for a long time and do well.

Q. PPID horse got loose manure on and off all winter when on liquid compound of pergolide, this year he is on Prascend, she increased the dose for the seasonal rise and reduced it in December, and he immediately got loose manure again. What are the possible causes?

M: PPID causes a decreased ability to deal with infection and parasites. Study looked at horses with PPID and they had higher fecal egg counts (FECs), so check FEC to check for worms and use strategic worming in consultation with vet. At the higher dose, the immune system was probably working better, therefore parasite burden should be investigated.

Also there may be problems with efficacy using compounded pergolide.

TLS: also consider any diet changes in December, e.g. starting hay – stalky hay has anecodotally been reported as causing diarrhoea. We sometimes see diarrhoea in horses on too high a dose of pergolide – when the dose is reduced, the diarrhoea disappears, with no increase in PPID clinical signs –

http://www.noahcompendium.co.uk/?id=-447754

Q. How important is owner’s relationship with their vet?

M: Important to have vet involved with PPID horse, lot of complexity in diagnosis and treatment, owner info is critical, keep good records – e.g. when coat sheds, feet, appetite, BCS, weight tape – to notice problems early. Schedule routine checks with vet. Have to keep on top of PPID.

Q. 16 year old gelding, ACTH normal but muscle loss, long curly coat, reoccuring laminitis despite controlled diet and exercise. Vet suggested starting on Prascend – is it a good idea to treat without a positive blood test?

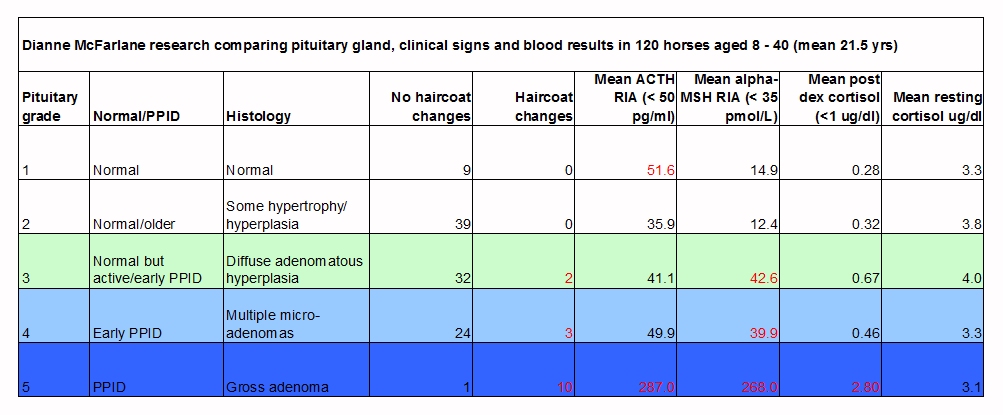

M: There’s a good clinical indication that this horse has PPID. If you suspect a horse has PPID, it almost always does have it, as test results often only become positive later in disease. The TRH stimulation of ACTH may be more effective at picking up early PPID. This horse is likely to benefit from Prascend.

TLS: insulin dysregulation should be tested in all cases of laminitis.

Q. How should you prioritise testing when finances are tight?

L: Depends what clinical signs the horse has, in more advanced cases where the horse has overt signs e.g. long shaggy haircoat, muscle loss, PU/PD, diagnostic tests may be less important as the clinical signs indicate PPID, treatment with pergolide would be warranted. Diagnostic testing may be more critical earlier in the disease if clinical signs are subtle, e.g. recurrent infection, change in behaviour which aren’t obviously PPID. Start with diagnostic test then follow up test to monitor treatment, then ideally follow up rechecks.

TLS: NB be aware that tests in early stages of PPID may give false negative results.

Q. 22 year old Morgan mare diagnosed with PPID in 2012, doing fairly well on pergolide. Concerned mare isn’t drinking enough which seems to cause dry manure and bouts of colic. Before starting pergolide the mare drank 5 gallons/day, now only 2 gallons/day. Can pergolide reduce thirst too much?

M: PPID horses can have PU/PD, but 5 gallons is not excessive so no reason to think this horse had PU/PD before treatment. Dr McFarlane has never seen pergolide reduce drinking other than correcting PU/PD. Pergolide does not reduce thirst. Is horse eating the same as it was before?

Q. Is there a difference between pergolide products in terms of effectiveness?

M: Research looked at some of the different compounded drugs compared to manufactured pergolide. Pergolide is extremely hard to compound, if compounding companies do not have all the right equipment they will end up with a product that is not consistent so you might not be giving your horse the dose you think you are. Pergolide is very unstable, it can degrade quickly, liquid forms degrade as it is sensitive to light and temp. When peroglide is correctly manufactured and packaged it is stable. 2 investigators have done 3 studies that have shown that the compounded drug is not stable. TLS: see under Pergolide http://www.thelaminitissite.org/p-q.html.

L: Recent unpublished data: 21 additional compounded pergolide forumulations were looked at at North Carolina State University, “out of those 21 common compounded formulations from major pharmacies at day 0 of the 6 month study only 4 of those compounds met the plus or minus 10% of labelled concentration, which is what would be acceptable. And in fact, 1 of those 4 there was absolutely no pergolide detectable during that 6 month time frame” (*this needs clarification – see end of notes). Plenty of data demonstrating the potency and stability issues with compounded pergolide.

M: Compounded drugs are not under regulatory control, don’t know that what it says on label is what’s in drug. Manufactured drug is guaranteed to contain what it says on the label.

L/M: 4 out of 21 that were plus or minus 10% at day 0 before chance to degrade.

Prascend is a 1 mg tablet packed in a nitrogen sealed blister pack.

Q. How should Prascend be given?

L: Prascend should be given as soon as it is taken out of the blister pack. Can be fed by hand, or dissolved in a bit of water. If the horse has insulin issues, use low sugar treats to give Prascend, e.g. sugar free pancake syrup. If no problem with insulin, put tablet in e.g. apple, carrot, apple sauce, grape. Find something horse likes to insert tablet in, may have to try something new every few weeks. Horses may go off feed if given with pergolide, so may need to give tablet at different time.

TLS: carrot on an as fed basis has less than 7% combined sugar/starch and a small amount should be safe to feed to any horse, insulin dysregulation or not: http://www.thelaminitissite.org/2/post/2013/03/who-said-stop-the-carrots.html.

Q. Are there any issues regarding vaccinating and worming for horses with PPID?

M: Vaccinate as any aged horse, depending on exposures to pathogens. PPID horses respond less rigourously to flu. Ongoing studies about how PPID horses respond to vaccines. FECs are important for PPID horses, as they can be high egg shedders, and worm strategically according to results, in consultation with your vet.

Q. Horse was diagnosed with PPID and had laminitis in spring 2013, can he be exercised as normal now?

M: The consideration regarding exercise is the laminitis. Horses with PPID can continue to work, and if one of the majority of horses that doesn’t have insulin problems and risk of laminitis, there shouldn’t be any concerns. Need to be sure the horse isn’t over-exercised if still any pain or inflammation in the feet. If the laminitis has been resolved and managed then horse should be able to return to exercise. Feet are limiting factor, work with vet and farrier to do corrective trimming and/or shoeing, take radiographs and be sure feet are resolved before doing much in the way of exercise.

TLS: a horse with active laminitis or founder should not be exercised at all and kept confined until the active laminitis has resolved and the feet have been realigned.

Q. Can chaste berry be given in addition to Prascend/at all?

M: Chaste berry is a herb with reportedly similar dopaminergic-type properties to pergolide. In herbal supplements we don’t know the amount of active substance (if any) from year to year, or forumulation to formulation. Dr Beech used chaste berry extract for horses with PPID and found no improvement, then found improvement when same horses were treated with manufactured pergolide. Don’t use, use only Prascend.

TLS: See Vitex agnus castus http://www.thelaminitissite.org/u-v-w-x-y-z.html.

Q. Numerous supplements/homeopathic treatments claim to help horses with PPID – do any work?

M: Very little research has been done, the ones tested have shown no improvement. Nothing can be recommended that has any science behind it to suggest that it is helpful.

Q. 28 mare that’s been on Prascend for 18 months, no recurrence of laminitis and a more normal haircoat. Started shedding in February but seems thin, can’t eat hay as bad teeth. On grass and concentrate mix, what else can she feed?

L: Start with thorough dental exam, every 6 months. Ensure good deworming programme. For diet, as she’s had laminitis she probably has insulin dysregulation so have to be careful with feed. If she can’t eat hay, make sure she is fed at least 2% of her bodyweight/day, recommend vegetable oil for calories ½ cup to 1 cup/day, rinsed and soaked unmolassed beet pulp for nutrients, fibre and water (to help prevent colic in horses with poor teeth), flax seed for EFAs and calories, and commercial supplements for weight gain, in addition to her concentrate mix.

Q. Is flaxseed (linseed in UK) good for PPID?

L: Excellent for equine diet – rich in protein, good for muscle wasting; omega 3 fatty acids; seed holds water so may help prevent colic; in humans may improve immune response, may be added benefit.

Q. Will PPID horses have improved FECs when treated with pergolide?

M: This is an area that needs to be studied. In theory it should, as Prascend improves immune function, but haven’t done FECs pre and post Prascend.

Q. Any supplements PPID horses should not have?

M: Can’t think of anything that would be contra-indicated in a typical supplement.

Q. 28 PPID gelding on pergolide and Thyro-L, never fully sheds, clipped in summer and autumn, can coat be made normal?

L: Haircoat should improve with adequate treatment, retest to ensure on proper dose, make sure actually getting dose! Check correct deworming programme, parasites can affect haircoat. Focus on diet, ensure balanced and supplying adequate protein, vitamins and minerals. Use Prascend not compounded pergolide.

Q. What is the life expectency for a horse with PPID with/without medication?

M: Horses with PPID can live a long time and have a high quality of life if well managed and able to avoid infectious diseases and laminitis if they have insulin dysregulation. If PPID well controlled with pergolide and good management, no reason they can’t live a long quality life, possibly into their 40s (Dr McFarlane knew a 45 year old with PPID) – PPID is not necessarily going to shorten life expectency.

Important that owners are proactive at recognising problems (e.g. infections and laminitis) before they become well established.

Q. Can a horse with PPID feel discomfort because of the increased size of the pituitary gland?

M: No indication that PPID horses have head pain. The hormones that are increased with PPID are anti-inflammatory and analgesic so PPID horses tend to feel good!

Q. Can PPID affect eyesight?

M: There are a few reports, but no direct link proven. 90% of old horses have eye lesions, old horses will have vision problems, not just PPID horses. Corneal ulcers heal slower with PPID.

Q. Should pergolide be given at the same time each day?

L: Give when most convenient, no recommendation for either morning or evening.

Q. Is an increase in tendon & ligament injuries seen with PPID?

M: No indication that PPID causes more problems with tendons and ligaments. However reports have been received of horses that have been lethargic due to PPID starting treatment and feeling too good, and injuring themselves when they are turned out! So rehab horses, warm up well before exercise – they may feel a lot younger than their body is!

Final thoughts.

L: Most important thing for owners to do is to be proactive – learn early signs of PPID, help vet with diagnosis, the earlier we recognise and manage PPID, better quality of life our horses will have.

M: PPID horses still have a lot to give, fabulous that owners are learning about PPID and taking care of these older horses.

www.thehorse.com/PPID - 10 articles about PPID

TLS:

*We’ve listened to this over and over – best sense we can make is that the FDA standard for potency is that there should be no more than a +/- 10% difference between the active ingredient actually in a drug and the active ingredient declared on the label.

So we are guessing that 4 out of the 21 compounded formulations looked at were found to have a difference of more than 10% between the actual amount of pergolide and the quantity on the label when they were first analysed (at day 0), and that 1 of these 4 had no pergolide detectable at all during the 6 months.

More about the stability and potency of pergolide in compounded products under pergolide: http://www.thelaminitissite.org/p-q.html

Interesting that lots of reference was made to horses being diagnosed later, i.e. in their teens, and a 13 year old horse was described as being young for diagnosis. However in the UK we are seeing horses being diagnosed younger than this – is this a result of the free testing campaigns by Talk About Laminitis picking up early cases of PPID at a younger age?

Disclaimer: No responsibility is taken for the accuracy of these notes.

The Horse Ask the Vet Live session is available on-line: http://www.thehorse.com/ask-the-vet/33389/managing-horses-with-ppid-equine-cushings

RSS Feed

RSS Feed