If you are looking for help because your horse has laminitis, EMS or PPID, please join Friends of TLS (FoTLS)

Equine Metabolic Syndrome/Insulin Dysregulation/Resistance

EMS - Need to know

What is Equine Metabolic Syndrome?

What is Insulin Resistance?

Why do some horses become Insulin Resistant?

How is Insulin Resistance/EMS diagnosed?

How is Insulin Resistance/EMS managed/treated?

EMS/IR news

Further information

What is Equine Metabolic Syndrome?

What is Insulin Resistance?

Why do some horses become Insulin Resistant?

How is Insulin Resistance/EMS diagnosed?

How is Insulin Resistance/EMS managed/treated?

EMS/IR news

Further information

EMS - Need to know

EMS is short for Equine Metabolic Syndrome.

EMS is not a disease, but a term used to describe a horse that shows risk factors associated with an increased risk of developing hyperinsulinemia-associated (endocrinopathic) laminitis - the most common form of laminitis. All horses with EMS have insulin dysregulation (ID), and often are overweight and/or have abnormal fat pads. EMS is influenced by genetics and management, with easy-keeper breeds needing stricter management.

Insulin dysregulation can mean hyperinsulinaemia (above normal insulin) at baseline or after normal feed or an oral sugar challenge, or tissue insulin resistance. ID can also be associated with corticosteroid use, PPID, some illnesses, pregnancy, stress and starvation.

More information: The Equine Endocrinology Group Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of EMS 2022.

EMS is short for Equine Metabolic Syndrome.

EMS is not a disease, but a term used to describe a horse that shows risk factors associated with an increased risk of developing hyperinsulinemia-associated (endocrinopathic) laminitis - the most common form of laminitis. All horses with EMS have insulin dysregulation (ID), and often are overweight and/or have abnormal fat pads. EMS is influenced by genetics and management, with easy-keeper breeds needing stricter management.

Insulin dysregulation can mean hyperinsulinaemia (above normal insulin) at baseline or after normal feed or an oral sugar challenge, or tissue insulin resistance. ID can also be associated with corticosteroid use, PPID, some illnesses, pregnancy, stress and starvation.

More information: The Equine Endocrinology Group Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of EMS 2022.

What is Equine Metabolic Syndrome?

|

Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) but may be defined as a cluster of factors that increase the risk of laminitis.

A horse with EMS will have - insulin dysregulation, which may be any combination of tissue insulin resistance, baseline hyperinsulinaemia (above normal insulin) and/or an abnormally high insulin response to sugar/starch eaten, and may also - be obese/overweight and/or have regional adiposity (fat deposits in the crest of the neck, sheath/mammary glands, above the tail and/or above the eyes), - have a history of laminitis, - have abnormal adiponectin or triglycerides. He/she will often have a history of easy weight gain from adulthood, a ravenous appetite and/or poor exercise tolerance. |

The term "Equine Metabolic Syndrome" was first proposed (in research) by Philip Johnson in 2002: Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2002 Aug;18(2):271-93

The equine metabolic syndrome peripheral Cushing's syndrome

Johnson PJ

Nicholas Frank published a review of EMS in 2011:

Frank N

Equine metabolic syndrome

Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2011 Apr;27(1):73-92 (PubMed)

"EMS shares some of the features of MetS, including increased adiposity, hyperinsulinemia, IR, but differs in that laminitis is the primary disease of interest."

"Equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) is a term used to describe an interrelated group of metabolic disturbances including hyperinsulinaemia, insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia and adiposity that often leads to endocrinopathic laminitis", with both genetic and environmental factors likely playing a role.

Norton EM, Schultz NE, Rendahl AK, Mcfarlane D, Geor RJ, Mickelson JR, McCue ME

Heritability of metabolic traits associated with equine metabolic syndrome in Welsh ponies and Morgan horses

Equine Vet J. 2019 Jul;51(4):475-480. doi: 10.1111/evj.13053. Epub 2018 Dec 15

The equine metabolic syndrome peripheral Cushing's syndrome

Johnson PJ

Nicholas Frank published a review of EMS in 2011:

Frank N

Equine metabolic syndrome

Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2011 Apr;27(1):73-92 (PubMed)

"EMS shares some of the features of MetS, including increased adiposity, hyperinsulinemia, IR, but differs in that laminitis is the primary disease of interest."

"Equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) is a term used to describe an interrelated group of metabolic disturbances including hyperinsulinaemia, insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia and adiposity that often leads to endocrinopathic laminitis", with both genetic and environmental factors likely playing a role.

Norton EM, Schultz NE, Rendahl AK, Mcfarlane D, Geor RJ, Mickelson JR, McCue ME

Heritability of metabolic traits associated with equine metabolic syndrome in Welsh ponies and Morgan horses

Equine Vet J. 2019 Jul;51(4):475-480. doi: 10.1111/evj.13053. Epub 2018 Dec 15

What is Insulin Resistance?

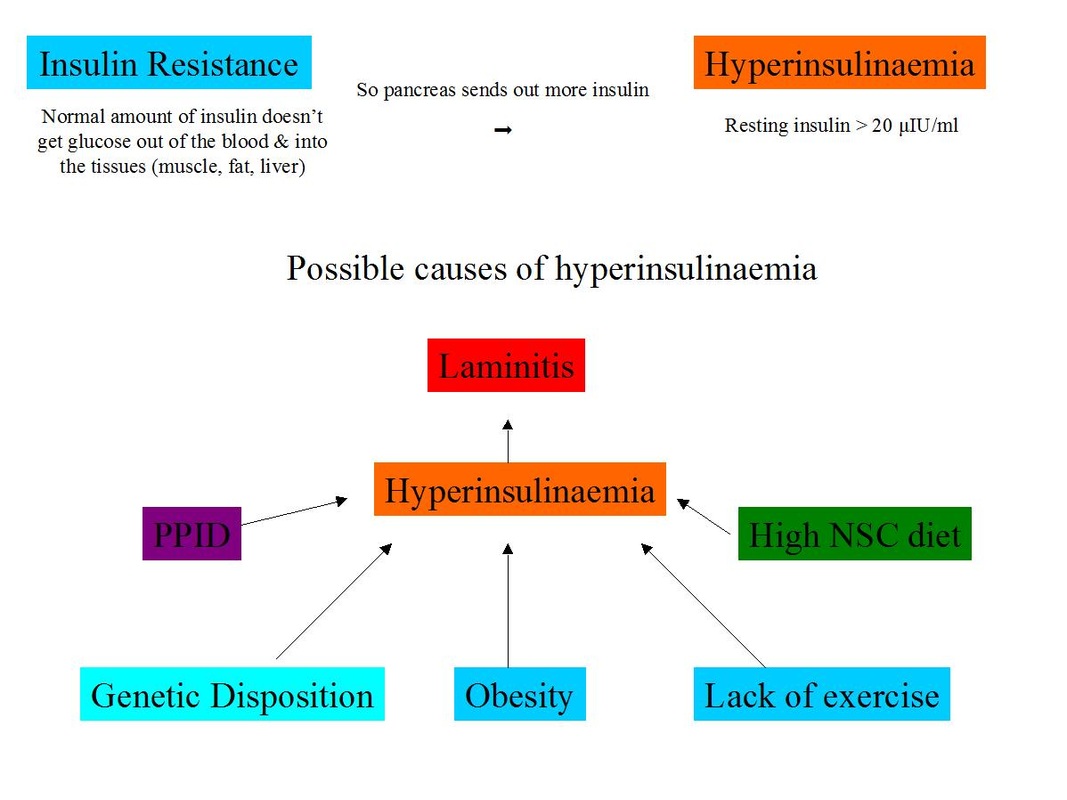

Insulin resistance can be defined as the inability of normal insulin concentrations to stimulate tissues to uptake glucose.

When a horse eats foods containing sugar or starch, glucose enters the blood, and this stimulates the pancreas to release insulin. When insulin attaches to insulin receptors, found on many cells in the body (muscle, fat, liver, heart), glucose is able to leave the bloodstream and enter the cell.

With insulin resistance, the cells become resistant to insulin - the normal amount of insulin no longer gets the job done, and therefore the pancreas has to compensate by releasing increased amounts of insulin to move the glucose into the cells, to prevent blood glucose levels becoming too high (hyperglycaemia).

This results in high blood insulin levels (hyperinsulinaemia), but glucose levels generally remain within the normal range (euglycaemia). Glucose levels above the normal range may indicate diabetes mellitus or PPID.

When a horse eats foods containing sugar or starch, glucose enters the blood, and this stimulates the pancreas to release insulin. When insulin attaches to insulin receptors, found on many cells in the body (muscle, fat, liver, heart), glucose is able to leave the bloodstream and enter the cell.

With insulin resistance, the cells become resistant to insulin - the normal amount of insulin no longer gets the job done, and therefore the pancreas has to compensate by releasing increased amounts of insulin to move the glucose into the cells, to prevent blood glucose levels becoming too high (hyperglycaemia).

This results in high blood insulin levels (hyperinsulinaemia), but glucose levels generally remain within the normal range (euglycaemia). Glucose levels above the normal range may indicate diabetes mellitus or PPID.

What is the difference between compensated IR, uncompensated IR and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus?

Compensated insulin resistance is by far the most common form of insulin resistance (insulin/glucose metabolism abnormality) seen in horses - the pancreas compensates for the decreased tissue response to circulating insulin by secreting more insulin, leading to above normal insulin concentrations (hyperinsulinaemia), which manage to get the glucose into the cells so glucose concentrations stay within normal ranges (euglycaemia), although may be towards the high end of normal.

Compensated insulin resistance is by far the most common form of insulin resistance (insulin/glucose metabolism abnormality) seen in horses - the pancreas compensates for the decreased tissue response to circulating insulin by secreting more insulin, leading to above normal insulin concentrations (hyperinsulinaemia), which manage to get the glucose into the cells so glucose concentrations stay within normal ranges (euglycaemia), although may be towards the high end of normal.

Compensated IR = increased insulin (> 20 µIU/ml) with normal glucose (< 100 mg/dl / 5.55 mmol/l)

Uncompensated insulin resistance may follow compensated insulin resistance if the pancreas starts to wear out - more technically referred to as pancreatic insufficiency or beta-cell exhaustion. Insulin concentrations are lower than expected in relation to the glucose concentration. Initially as the horse transitions from compensated IR to uncompensated IR, both insulin (hyperinsulinaemia) and glucose (hyperglycaemia) concentrations may be above normal, but once the pancreas is no longer compensating, insulin concentrations fall back into the normal range and glucose concentrations remain above normal. Uncompensated IR could be due to PPID.

Transitioning to uncompensated IR = increased insulin (> 20 µIU/ml) with increased glucose (> 100 mg/dl / 5.55 mmol/l)

Uncompensated IR = normal insulin (< 20 µIU/ml) and increased glucose (> 120 mg/dl / 6.66 mmol/l)

Uncompensated IR = normal insulin (< 20 µIU/ml) and increased glucose (> 120 mg/dl / 6.66 mmol/l)

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) may follow uncompensated insulin resistance when pancreatic failure and the resulting hyperglycaemia leads to glucosuria (glucose in the urine) and excess drinking and urination. T2DM could be due to PPID.

What is the difference between EMS and PPID?

Horses with both EMS and PPID can have regional adiposity, hyperinsulinaemia and laminitis. Horses with PPID are often, but not always, insulin resistant. With PPID, it is the loss of dopamine producing neurons that ultimately leads to hyperinsulinaemia. With EMS, it is likely that obesity, lack of exercise, genetics and diet can all lead to hyperinsulinaemia. Testing for PPID using the resting ACTH concentration should differentiate between a horse with EMS only and a horse with PPID (although tests are not 100% accurate). This is important because a horse with unrecognised PPID that is being treated only for EMS is unlikely to improve significantly without pergolide. There is currently no reason to think that a horse will benefit from pergolide if it has EMS but does not have PPID.

Horses with both EMS and PPID can have regional adiposity, hyperinsulinaemia and laminitis. Horses with PPID are often, but not always, insulin resistant. With PPID, it is the loss of dopamine producing neurons that ultimately leads to hyperinsulinaemia. With EMS, it is likely that obesity, lack of exercise, genetics and diet can all lead to hyperinsulinaemia. Testing for PPID using the resting ACTH concentration should differentiate between a horse with EMS only and a horse with PPID (although tests are not 100% accurate). This is important because a horse with unrecognised PPID that is being treated only for EMS is unlikely to improve significantly without pergolide. There is currently no reason to think that a horse will benefit from pergolide if it has EMS but does not have PPID.

Why do some horses become insulin resistant?Individual factors

Genetic disposition for Insulin Resistance - “thifty gene” to survive harsh winter/drought - native ponies, Arabs, Iberians, Haflingers... More efficient energy metabolism - “easy keepers” Increased appetite - leptin (“stop eating, you’re full" hormone) resistant Possible differences in nutrient digestion/absorption Environmental factors Overfeeding - large fields, improved grasses, cereals Elimination of seasonal weight loss Lack of exercise Higher standards of care - rugs, worming, teeth Obesity not recognised |

How is Insulin Resistance/EMS diagnosed?

1. Screening blood tests - insulin and glucose

Initially basal/baseline insulin and glucose concentrations should be measured (plus ACTH if PPID is a possibility). Just one blood draw is necessary, but more than one blood draw will increase the accuracy of diagnosis.

To fast or not?

The ACVIM consensus statement on Equine Metabolic Syndrome suggests a fasting protocol:

Feed 1 flake of low NSC hay no later than 10pm the night before testing,

Collect blood between 8 am and 10 am the following morning - this should ensure a 6 hour period of fasting.

Measure glucose and insulin concentrations.

Interpreting results

Insulin - fasting insulin is generally considered normal below 20 µIU/ml (138.9 pmol/l) (normal ranges can differ between laboratories using different assay methods - using a laboratory with widely accepted normal ranges can avoid confusion). Therefore a fasting insulin concentration > 20 µIU/ml (138.9 pmol/l) is diagnostic of insulin resistance.

Horses with insulin resistance can have a normal resting insulin concentration. If there is reason to suspect IR/EMS but a basal insulin test is normal, dynamic testing should be considered.

Hyperinsulinemia can be caused by stress, pain, recent feeding. Insulin concentrations are likely to be raised in a horse currently suffering from laminitis, therefore insulin testing should ideally be delayed until the pain and stress have lessened.

Glucose - fasting glucose should be inside the laboratory's normal range (e.g.< 110 mg/dl (6.11 mmol/l)).

Hyperglycemia is rarely found in horses with insulin resistance, although glucose concentrations are often towards the high end of the normal reference range. Hyperglycemia may indicate Type 2 diabetes mellitus or PPID.

Hyperglycemia can be caused by stress, pain, recent feeding, some drugs and inflammatory processes.

2. Dynamic testing - carried out when screening tests are inconclusive

In a hospital setting, the Combined Glucose-Insulin Tolerance Test (CGITT) may be used.

More commonly the oral sugar/glucose test (OST/OGT) is used.

1 flake of low NSC hay is given no later than 10pm the night before testing.

The following morning the owner gives the horse an agreed amount of glucose/dextrose - e.g. in the UK a chaff feed is often given with 1g/kg bodyweight glucose or dextrose, in the USA 0.15 ml/kg bodyweight Karo Light Syrup (corn syrup) is given (this can be syringed directly into the horse's mouth).

60 - 120 minutes later the vet draws a sample of blood to test insulin and glucose concentrations.

Interpreting results:

Depending on the laboratory, Insulin > 60 or 85 µIU/ml may be considered diagnostic of insulin resistance for the OST/OGT.

As with screening tests, pain, stress and recent feeding will affect results and should be avoided.

Diagnosis of the Equine Metabolic Syndrome - The Liphook Equine Hospital and Laboratory

Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center - Equine Metabolic Syndrome Tests

Diagnostic tests for insulin resistance - see p15 onwards:

Wearn JMG

A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of pioglitazone in a model of induced insulin resistance in normal horses

MSc thesis 2010

Initially basal/baseline insulin and glucose concentrations should be measured (plus ACTH if PPID is a possibility). Just one blood draw is necessary, but more than one blood draw will increase the accuracy of diagnosis.

To fast or not?

The ACVIM consensus statement on Equine Metabolic Syndrome suggests a fasting protocol:

Feed 1 flake of low NSC hay no later than 10pm the night before testing,

Collect blood between 8 am and 10 am the following morning - this should ensure a 6 hour period of fasting.

Measure glucose and insulin concentrations.

Interpreting results

Insulin - fasting insulin is generally considered normal below 20 µIU/ml (138.9 pmol/l) (normal ranges can differ between laboratories using different assay methods - using a laboratory with widely accepted normal ranges can avoid confusion). Therefore a fasting insulin concentration > 20 µIU/ml (138.9 pmol/l) is diagnostic of insulin resistance.

Horses with insulin resistance can have a normal resting insulin concentration. If there is reason to suspect IR/EMS but a basal insulin test is normal, dynamic testing should be considered.

Hyperinsulinemia can be caused by stress, pain, recent feeding. Insulin concentrations are likely to be raised in a horse currently suffering from laminitis, therefore insulin testing should ideally be delayed until the pain and stress have lessened.

Glucose - fasting glucose should be inside the laboratory's normal range (e.g.< 110 mg/dl (6.11 mmol/l)).

Hyperglycemia is rarely found in horses with insulin resistance, although glucose concentrations are often towards the high end of the normal reference range. Hyperglycemia may indicate Type 2 diabetes mellitus or PPID.

Hyperglycemia can be caused by stress, pain, recent feeding, some drugs and inflammatory processes.

2. Dynamic testing - carried out when screening tests are inconclusive

In a hospital setting, the Combined Glucose-Insulin Tolerance Test (CGITT) may be used.

More commonly the oral sugar/glucose test (OST/OGT) is used.

1 flake of low NSC hay is given no later than 10pm the night before testing.

The following morning the owner gives the horse an agreed amount of glucose/dextrose - e.g. in the UK a chaff feed is often given with 1g/kg bodyweight glucose or dextrose, in the USA 0.15 ml/kg bodyweight Karo Light Syrup (corn syrup) is given (this can be syringed directly into the horse's mouth).

60 - 120 minutes later the vet draws a sample of blood to test insulin and glucose concentrations.

Interpreting results:

Depending on the laboratory, Insulin > 60 or 85 µIU/ml may be considered diagnostic of insulin resistance for the OST/OGT.

As with screening tests, pain, stress and recent feeding will affect results and should be avoided.

Diagnosis of the Equine Metabolic Syndrome - The Liphook Equine Hospital and Laboratory

Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center - Equine Metabolic Syndrome Tests

Diagnostic tests for insulin resistance - see p15 onwards:

Wearn JMG

A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of pioglitazone in a model of induced insulin resistance in normal horses

MSc thesis 2010

How is EMS/IR managed/treated?

1. Weight loss if the horse is overweight/obese.

2. Low sugar/starch diet and exercise to increase insulin sensitivity.

3. In some cases medical treatments are advised.

Management strategies for EMS/IR include using slow feeder systems, small holed hay nets, track systems, grazing muzzles, strip grazing, bare paddocks, more..

Management of Equine Metabolic Syndrome - Nicholas Frank (2011)

Research into potential treatments

Meier A, Reiche D, de Laat M, Pollitt C, Walsh D, Sillence M

The sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor velagliflozin reduces hyperinsulinemia and prevents laminitis in insulin-dysregulated ponies

PLoS ONE 13(9): e0203655 published 13 Sept 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203655

See also: Drug shows promises in preventing laminitis in at-risk ponies - www.horsetalk.co.nz 24 Sept 2018

Successful treatments

Delarocque J, Frers F, Huber K, Feige K, Warnken T

Weight loss is linearly associated with a reduction of the insulin response to an oral glucose test in Icelandic horses

BMC Veterinary Research Published online 24 May 2020 16:151 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02356-w

Morgan RA, Keen JA, McGowan CM

Treatment of Equine Metabolic Syndrome: a clinical case series

Equine Veterinary Journal published online March 2015

Owners of 19 horses with EMS but not PPID, 17 of which had a history of laminitis, were given individually tailored diet and exercise programmes to follow for 3-6 months. A reduction in body condition score was seen in all horses (from median 4.5/5 to 3/5); a reduction in bodyweight in 18/19 horses (average from 400 kg to 397.4 kg); and reductions in resting insulin seen (from average 33.71 to 9.82 mIU/L.

Conclusion: A diet and exercise programme individually tailored and carried out by the owner results in weight loss and improvements in insulin sensitivity.

Equine Veterinary Journal Volume 44, Issue Supplement s42, Article first published online: 13 SEP 2012

Abstract #17 THE CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF EMS AT THE PHILIP LEVERHULME EQUINE HOSPITAL

Hudson, A.B., McGowan, C. and Morgan, R.

9 horses with EMS following a veterinary prescribed diet and exercise plan for an average of 16 weeks lost weight, had a reduced BCS and had reduced basal insulin values (55.7 uIU/ml to 11.2 uIU/ml on average) and an improved CGIT result.

Donaldson et al. 2004 - 1 horse with laminitis, a high insulin and glucose concentration, a cresty neck and BCS of 8/9 (i.e. obese) was treated with phenylbutazone, corrective trimming and a restricted diet, and after 4 months had insulin and glucose concentrations within normal ranges, was sound, and had a BCS of 5/9.

Rosie

2. Low sugar/starch diet and exercise to increase insulin sensitivity.

3. In some cases medical treatments are advised.

Management strategies for EMS/IR include using slow feeder systems, small holed hay nets, track systems, grazing muzzles, strip grazing, bare paddocks, more..

Management of Equine Metabolic Syndrome - Nicholas Frank (2011)

Research into potential treatments

Meier A, Reiche D, de Laat M, Pollitt C, Walsh D, Sillence M

The sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor velagliflozin reduces hyperinsulinemia and prevents laminitis in insulin-dysregulated ponies

PLoS ONE 13(9): e0203655 published 13 Sept 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203655

See also: Drug shows promises in preventing laminitis in at-risk ponies - www.horsetalk.co.nz 24 Sept 2018

Successful treatments

Delarocque J, Frers F, Huber K, Feige K, Warnken T

Weight loss is linearly associated with a reduction of the insulin response to an oral glucose test in Icelandic horses

BMC Veterinary Research Published online 24 May 2020 16:151 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02356-w

Morgan RA, Keen JA, McGowan CM

Treatment of Equine Metabolic Syndrome: a clinical case series

Equine Veterinary Journal published online March 2015

Owners of 19 horses with EMS but not PPID, 17 of which had a history of laminitis, were given individually tailored diet and exercise programmes to follow for 3-6 months. A reduction in body condition score was seen in all horses (from median 4.5/5 to 3/5); a reduction in bodyweight in 18/19 horses (average from 400 kg to 397.4 kg); and reductions in resting insulin seen (from average 33.71 to 9.82 mIU/L.

Conclusion: A diet and exercise programme individually tailored and carried out by the owner results in weight loss and improvements in insulin sensitivity.

Equine Veterinary Journal Volume 44, Issue Supplement s42, Article first published online: 13 SEP 2012

Abstract #17 THE CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF EMS AT THE PHILIP LEVERHULME EQUINE HOSPITAL

Hudson, A.B., McGowan, C. and Morgan, R.

9 horses with EMS following a veterinary prescribed diet and exercise plan for an average of 16 weeks lost weight, had a reduced BCS and had reduced basal insulin values (55.7 uIU/ml to 11.2 uIU/ml on average) and an improved CGIT result.

Donaldson et al. 2004 - 1 horse with laminitis, a high insulin and glucose concentration, a cresty neck and BCS of 8/9 (i.e. obese) was treated with phenylbutazone, corrective trimming and a restricted diet, and after 4 months had insulin and glucose concentrations within normal ranges, was sound, and had a BCS of 5/9.

Rosie

Further information:

Durham AE, Frank N, McGowan CM, Menzies-Gow NJ, Roelfsema E, Vervuert I, Feige K, Fey K

ECEIM consensus statement on equine metabolic syndrome

J Vet Intern Med. Published online 6 Feb 2019. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15423

Common medical challenges with ageing horses - Andy Durham Feb 2018

Morgan R, Keen J, McGowan C

Equine metabolic syndrome

Veterinary Record Aug 2015;177:173-179 doi:10.1136/vr.103226

Bertin FR, de Laat MA

The diagnosis of equine insulin dysregulation

Equine Veterinary Journal Volume 49, Issue 5 September 2017 Pages 570–576

Equine Metabolic Syndrome - Redwings leaflet

Obesity & Insulin Resistance in Horses: Management & Prevention - Philip J Johnson - 84th Annual Western Veterinary Conference 2012

Equine Metabolic Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment - Nicholas Frank FAEP 49th Annual Ocala Equine Conference Oct 2011

Frank N

Equine metabolic syndrome

Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2011 Apr;27(1):73-92

Guide to Insulin Resistance & Laminitis (2008)– Nicholas Frank, Raymond Geor, Steve Adair

ACVIM Consensus Statement Equine Metabolic Syndrome (2010)

ECIRhorse: Insulin Resistance - general and symptoms / Physiology of insulin resistance / Diet / Diagnosis / Trim / Treatment of Insulin Resistance / Treatment of laminitis

Current Therapy in Equine Medicine 2009 - Chapter 159 - Insulin Resistance and Equine Metabolic Syndrome - Nicholas Frank

Pathology of Metabolic–Related Conditions (2009) – Frank Andrews & Nicholas Frank

Insulin Resistance - What Is It and How Do We Measure It? - Stephanie Valberg & Anna Firshman

The HORSE.com fact sheet: Equine Insulin Resistance

Online courses with Dr Eleanor Kellon VMD in Cushing’s and Insulin Resistance, nutrition (NRC plus) and other subjects useful to owners of laminitic horses

Equine metabolic syndrome

Veterinary Record Aug 2015;177:173-179 doi:10.1136/vr.103226

Bertin FR, de Laat MA

The diagnosis of equine insulin dysregulation

Equine Veterinary Journal Volume 49, Issue 5 September 2017 Pages 570–576

Equine Metabolic Syndrome - Redwings leaflet

Obesity & Insulin Resistance in Horses: Management & Prevention - Philip J Johnson - 84th Annual Western Veterinary Conference 2012

Equine Metabolic Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment - Nicholas Frank FAEP 49th Annual Ocala Equine Conference Oct 2011

Frank N

Equine metabolic syndrome

Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2011 Apr;27(1):73-92

Guide to Insulin Resistance & Laminitis (2008)– Nicholas Frank, Raymond Geor, Steve Adair

ACVIM Consensus Statement Equine Metabolic Syndrome (2010)

ECIRhorse: Insulin Resistance - general and symptoms / Physiology of insulin resistance / Diet / Diagnosis / Trim / Treatment of Insulin Resistance / Treatment of laminitis

Current Therapy in Equine Medicine 2009 - Chapter 159 - Insulin Resistance and Equine Metabolic Syndrome - Nicholas Frank

Pathology of Metabolic–Related Conditions (2009) – Frank Andrews & Nicholas Frank

Insulin Resistance - What Is It and How Do We Measure It? - Stephanie Valberg & Anna Firshman

The HORSE.com fact sheet: Equine Insulin Resistance

Online courses with Dr Eleanor Kellon VMD in Cushing’s and Insulin Resistance, nutrition (NRC plus) and other subjects useful to owners of laminitic horses

Useful resources for EMS/ID

Equine Endocrinology Group - Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) 2018

Equine Endocrinology Group - Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) 2018

EMS/IR webcasts and videos

The Laminitis Revolution - David Rendle - 10 April 2013

Archived webcasts from the University of Minnesota:

Risk Factors for EMS - Dr Nichol Schultz - 29 Jan 2013

EMS and ponies - Dr Nicholas Frank - 18 Oct 2011

Equine Metabolic Syndrome - Dr Raymond Geor - 19 October 2010

Archived webcasts from the University of Minnesota:

Risk Factors for EMS - Dr Nichol Schultz - 29 Jan 2013

EMS and ponies - Dr Nicholas Frank - 18 Oct 2011

Equine Metabolic Syndrome - Dr Raymond Geor - 19 October 2010

1 hour webcast by Dr Ray Geor on Equine Metabolic Syndrome - My Horse University, Michigan State University

The term equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) is used to describe the clustering of obesity (and/or regional accumulations of fat), insulin resistance and increased susceptibility to laminitis in horses and ponies. In fact, EMS is now regarded as the most common cause of laminitis. This presentation will review the clinical features, diagnosis and medical management of EMS, and discuss dietary and exercise measures for mitigation of laminitis risk in affected animals. (From 2011 or 2015?).

The term equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) is used to describe the clustering of obesity (and/or regional accumulations of fat), insulin resistance and increased susceptibility to laminitis in horses and ponies. In fact, EMS is now regarded as the most common cause of laminitis. This presentation will review the clinical features, diagnosis and medical management of EMS, and discuss dietary and exercise measures for mitigation of laminitis risk in affected animals. (From 2011 or 2015?).