|

Laminitis

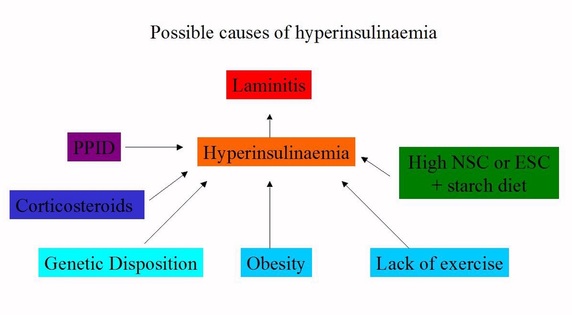

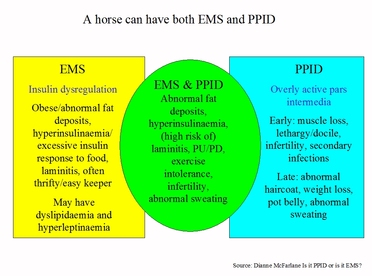

Every spring rapidly growing, high sugar grass will trigger endocrinopathic laminitis in many horses and ponies, which may result in euthanasia if correct treatment and foot care are not received. Around 90% of all laminitis cases - including all pasture associated laminitis - are now thought to have an endocrine cause - that is, they are due to insulin dysregulation (ID) - and are often associated with a diet high in sugar and/or starch (the other 10% of cases being sepsis-related or supporting limb laminitis). Horses with endocrinopathic laminitis will have Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) or PPID + ID (Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction), formerly known as equine Cushing’s disease. |

|

What is laminitis?

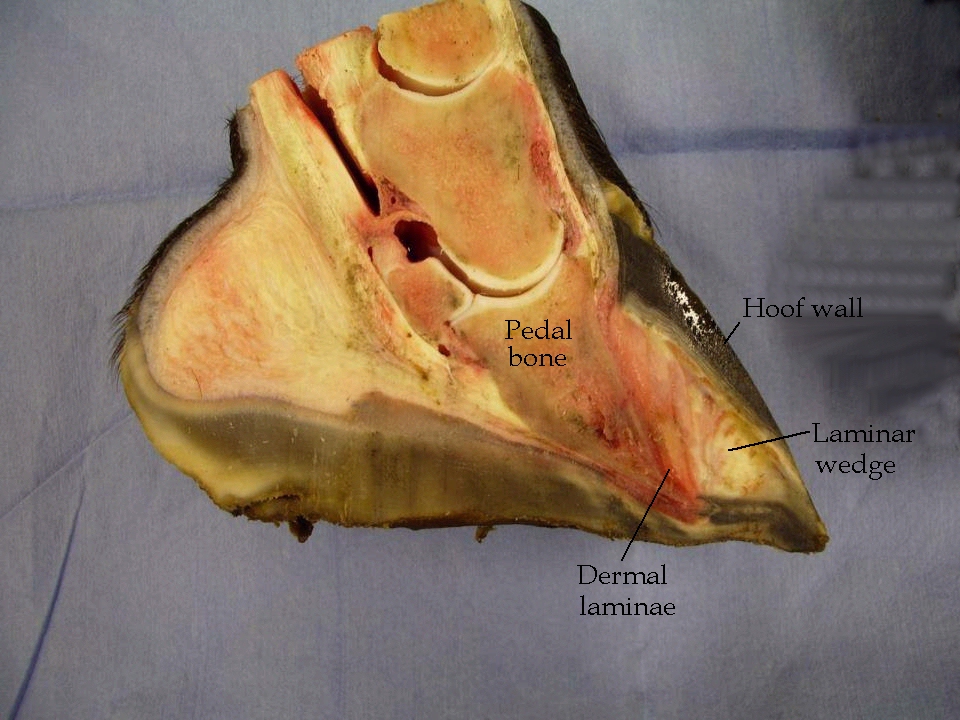

In a healthy horse the hoof wall wraps around the pedal (coffin) bone and is connected to it by laminae (also called lamellae) - interlocking cells often compared to velcro. The abnormally high levels of insulin seen with endocrinopathic laminitis are thought to cause the laminae to stretch and thereby weaken, often leading to the hoof capsule and bone moving away from each other – rotating and/or sinking - under the horse's weight. This can damage tissue, blood supply and nerves, causing pain, and eventually cell death, bone loss and sepsis if the damage is left uncorrected. Forget inflammation - little inflammation is thought to be involved in endocrinopathic laminitis. Laminitis is described as chronic once rotation and/or sinking have occurred. |

|

How is laminitis recognised?

Symptoms of laminitis vary considerably, and range from the horse appearing to be sound but having signs of chronic laminitis in the feet (e.g. hoof rings wider at the heels, a stretched white line and radiographic changes), through the horse being “footy” or short-strided on hard ground, unwilling to turn or trot, shifting weight from foot to foot and having a bounding digital pulse, to lying down most of the time with an increased heart and respiration rate. Laminitis can quickly progress from mild to severe and should always be taken seriously. More.. |

How is laminitis treated?

The cause must be identified and removed/treated, and the feet must be supported and fully realigned. With correct treatment, even significant damage to the feet can often be repaired and the horse returned to health.

The cause must be identified and removed/treated, and the feet must be supported and fully realigned. With correct treatment, even significant damage to the feet can often be repaired and the horse returned to health.

- VET - laminitis should always be considered an emergency – call your vet (and farrier/trimmer).

- SUPPORT - ensure the feet are well supported and protected from hard ground/surfaces with full solar surface conforming padding, e.g. boots with thick soft pads or taped on EVA foam pads cut to size. Bedding may provide sufficient support. See also: Sole Support.

- CONFINE - confine the horse on wall-to-wall reasonably deep conforming bedding, e.g. sawdust, shavings, sand, to limit movement (pad the feet before moving the horse to the area of confinement, and keep movement to a minimum, e.g. by using a low-loading trailer). If a stable isn't available or suitable, a fenced off shelter or even a stable-sized corner of a field can be used.

- DIET - remove the horse from grass and feed a low (<10%) sugar/starch diet based on analysed or soaked hay, plus minerals, vitamins, protein and essential fatty acids to meet minimum requirements. Never starve a horse with laminitis because of the risk of inducing hyperlipaemia – feed no less than 1.5% of the horse’s bodyweight per day (unless under veterinary supervision, and never less than 1.2%). More..

- PAIN RELIEF - pain relief such as Bute or Danilon may be prescribed to reduce the pain but may not treat the cause of the laminitis – it is now recognised that there is little inflammation involved in endocrine laminitis. If pain relief is still required after a week, it may be that the cause of the laminitis hasn’t been correctly identified and removed/treated, and/or the feet haven’t been correctly supported and realigned, and the case should be reassessed. Sub-solar abscesses can increase pain following laminitis.

|

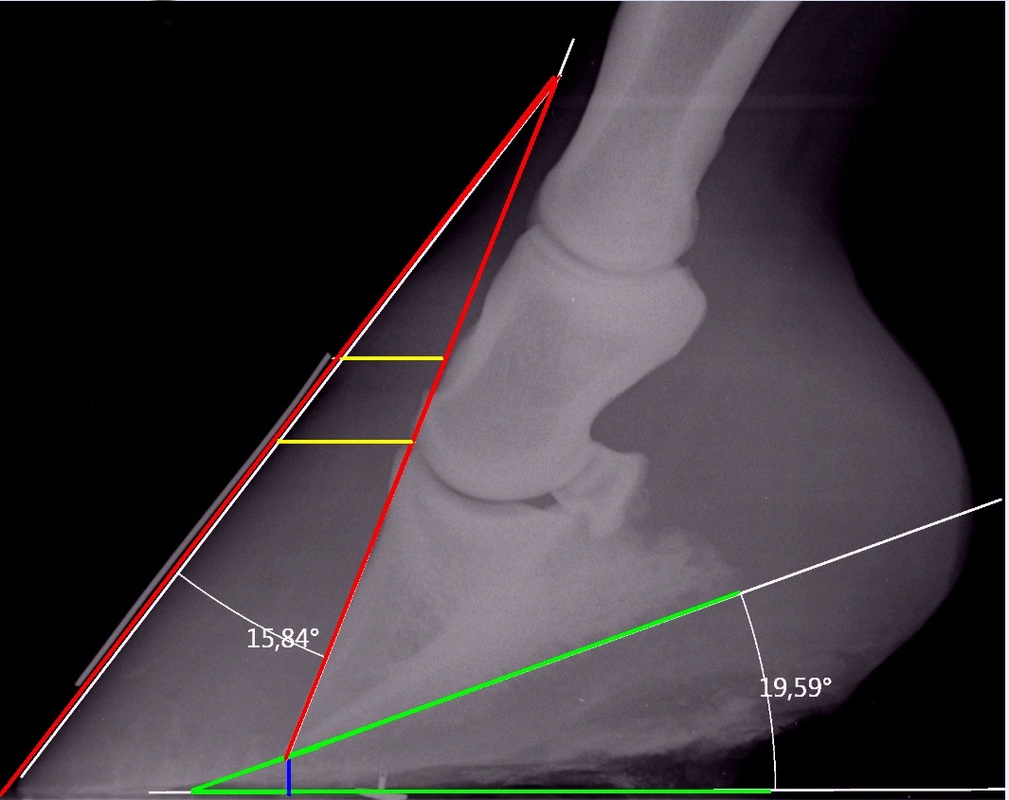

X-ray showing 15 degree dorsal rotation (red), 19 degree palmar rotation (green), sinking (yellow) and insufficient sole depth (blue) following laminitis induced by corticosteroid use (thanks to Pat for photo use) - see Casareño's recovery

|

|

Equine Metabolic Syndrome

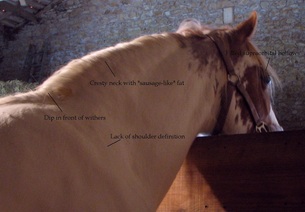

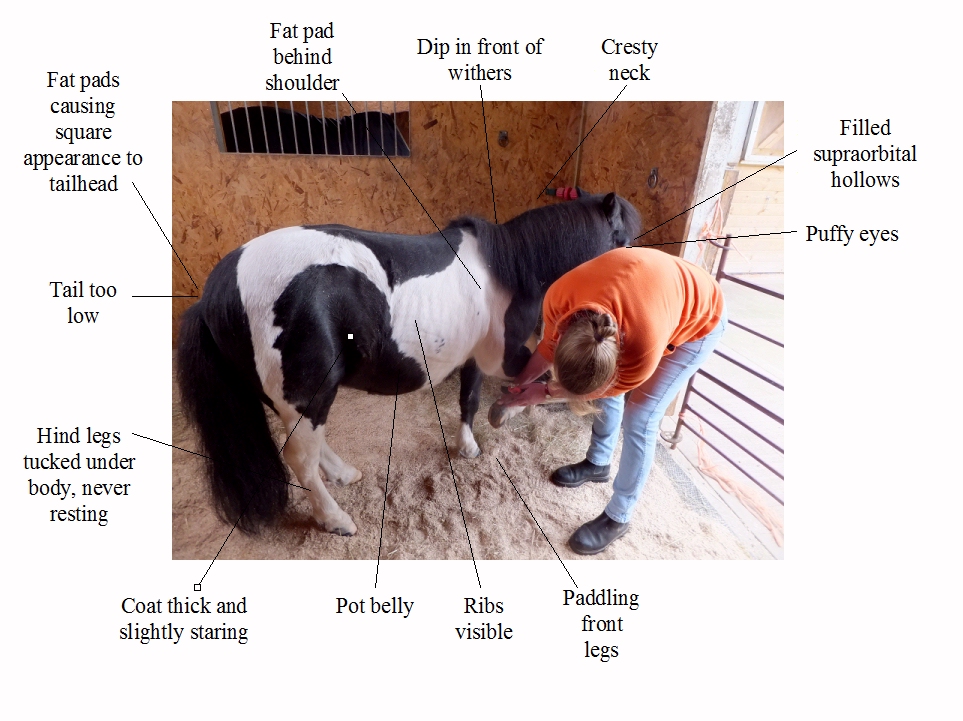

EMS is not a disease but a cluster of factors that increase the risk of laminitis. Often seen in “easy keeper” breeds including native ponies, Arabians and Iberians, a horse with EMS will usually have:

|

This mare with EMS has a large solid neck crest with “sausage-like” fat deposits, a dip in front of the withers, and filled supraorbital hollows. A lack of shoulder definition, gullet along her spine and inability to feel her ribs easily indicate that she is very overweight - see Rosie

|

|

Diagnosis is based on blood tests showing above normal resting insulin levels after eating hay, or an oral sugar test (using Karo Light corn syrup), plus symptoms and history. Note that a normal resting insulin result may not rule out EMS. Glucose may be tested but is usually normal.

Treatment is weight loss if necessary, a low sugar/starch diet that provides all essential nutrients, and exercise when the horse is able. The human antidiabetes drug Metformin is sometimes prescribed when a horse has high insulin levels and cannot exercise due to laminitis, but it has low bioavailability, research suggests that its use may be questionable when a horse is on a low sugar/starch diet, and drug treatment should not be a substitute for correct diet. Note that the use of corticosteroid drugs increases insulin levels, and carries a high risk of causing laminitis in susceptible horses. |

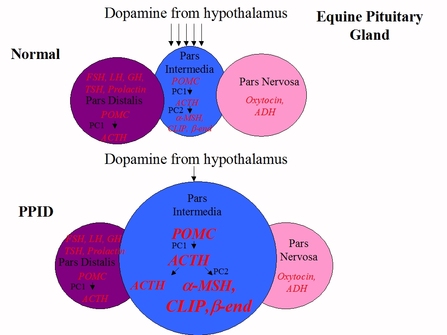

Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction

PPID is a progressive disease that starts when dopamine-producing neurons in the brain die, possibly due to oxidative damage, causing the pars intermedia in the pituitary gland to release excessive amounts of several hormones (alpha-MSH, beta-endorphin, ACTH and CLIP), and eventually leading to enlargement of the gland.

PPID is a progressive disease that starts when dopamine-producing neurons in the brain die, possibly due to oxidative damage, causing the pars intermedia in the pituitary gland to release excessive amounts of several hormones (alpha-MSH, beta-endorphin, ACTH and CLIP), and eventually leading to enlargement of the gland.

|

Clinical signs vary between horses and the stage of the disease, and include muscle loss, a pot belly, lethargy, recurrent infections, increased worm burdens, infertility, weight loss and abnormal sweating, and horses with PPID and EMS may have laminitis, insulin dysregulation, abnormal fat pads and excess drinking/urination. The long curly coat that doesn’t shed is a sign of advanced PPID, but early signs include long hair on the legs, face and neck, and late or patchy shedding. Symptoms are often worse in the autumn.

|

|

Early PPID can be hard to diagnose with the tests currently available – blood tests are often negative and signs of PPID overlap with normal ageing. Diagnosis is based on above normal ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) plus clinical signs and history. Testing ACTH between August and October may give the best results, using seasonal reference ranges, and the TRH (thyrotropin releasing hormone) stimulation of ACTH may be used outside of these months if resting ACTH results are equivocal. Not all horses with PPID appear to be at increased risk of laminitis, and insulin should always be tested as well as ACTH to identify those with insulin dysregulation and therefore an increased risk of laminitis.

|

PPID is treated with daily pergolide (now licensed for horses in many countries as Prascend, and also available as a paste from BOVA UK) to replace the missing dopamine, plus optimized management, with attention to providing a diet that provides all essential nutrients, clipping and rugging if necessary, good dental and foot care and targeted parasite control.

Horses with EMS may be at greater risk of developing PPID as they get older, and it has been suggested that they may have a greater risk of laminitis as they transition from EMS to PPID.

Horses with EMS may be at greater risk of developing PPID as they get older, and it has been suggested that they may have a greater risk of laminitis as they transition from EMS to PPID.

Nutmeg displaying signs of PPID, EMS and chronic laminitis - see Nutmeg's TLS rehab

How can laminitis be prevented?

The good news is that many cases of endocrine laminitis can be prevented with careful management and simple daily checks for at-risk horses:

The good news is that many cases of endocrine laminitis can be prevented with careful management and simple daily checks for at-risk horses:

|

- Feed a low sugar, low starch high fibre diet supplemented to provide above minimum levels of minerals, vitamins, protein and essential fatty acids.

- Restrict or prevent grazing when grass is growing fast (increased quantity), or during sunny weather and/or if stressed by drought or cold nights (increased sugar). Consider using a track (fencing off a strip around the outside of a field), grazing muzzle, and/or strip grazing to limit grass consumption and encourage movement. See When the grass is greener (University of Liverpool 2018) for good ideas for reducing grass intake and encouraging weight loss.

A grazing muzzle combined with track system allows horses with insulin dysregulation to socialise and exercise (thanks to Fiona for photo use) - see Sorrel's case study

- Ensure horses are regularly exercised as long as their feet are correctly aligned and stable. If exercise is reduced, consider reducing the energy content of feed – many cases of laminitis follow a reduction in exercise due to lameness, rider illness/holiday or bad weather.

- Keep feet perfectly balanced and supported, and check regularly for any signs of chronic laminitis – if signs are seen, have x-rays taken and ensure feet are fully realigned as soon as possible.

- Be vigilant for clinical signs of EMS and PPID, and arrange blood tests if suspicious – the aim is to diagnose and treat these conditions before laminitis occurs.

|

Daily checks that can help early identification of laminitis include:

|

If there is any suspicion of laminitis, follow the treatment protocol above.

What we know about laminitis has changed significantly in the last few years. For the latest information visit www.thelaminitissite.org and www.facebook.com/TheLaminitisSite.

What we know about laminitis has changed significantly in the last few years. For the latest information visit www.thelaminitissite.org and www.facebook.com/TheLaminitisSite.

A version of this article was first published in The Arabian Magazine March 2015 - download pdf file of The Arabian Magazine article.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed