Often seen in “easy keeper” breeds including native ponies, Arabians, Morgans and Iberians, a horse with EMS will usually have:

1. General obesity or regional adiposity (a cresty neck, filled supraorbital hollows, fat behind the shoulders and around the tailhead, swelling around the sheath/mammory glands);

3. A predisposition to or history of laminitis - signs of chronic laminitis such as hoof rings wider at the heels, a less-than-tight white line and a change of angle in the hoof wall may be seen in the feet, and x-rays may show rotation and remodelling of the pedal bone.

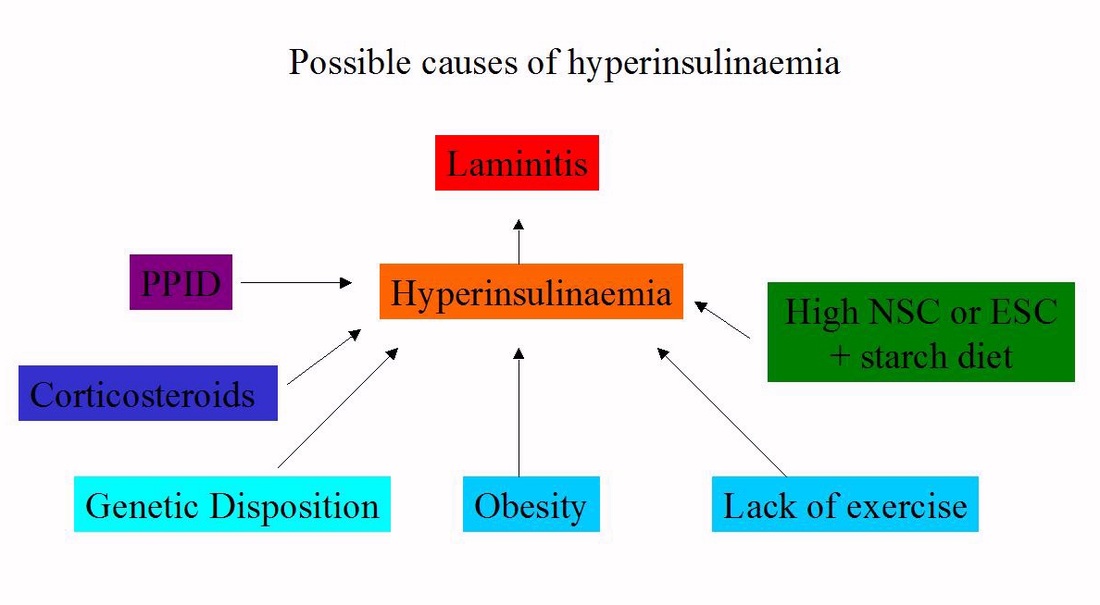

Obesity develops when horses have too much food and too little exercise. As the horse becomes obese and fat cells become full, the insulin signaling pathway is disrupted, causing insulin resistance. Fat cells release pro-inflammatory chemicals that cause systemic inflammation, and hormones including leptin, a “stop eating” hormone released when the horse has excess energy stored. High levels of leptin cause the target cells to become less receptive, or resistant, to the message to stop eating, so the horse continues to eat and put on weight. Obesity may also affect liver function resulting in reduced insulin clearance and consequent hyperinsulinaemia.

Research has suggested that weight gain has a greater impact on insulin sensitivity in certain breeds, with Arabians becoming insulin resistant when fed excess energy, but Thoroughbreds showing no decrease in insulin sensitivity with weight gain.

1. Cresty neck score from 0 to 5, with scores of 3 or greater often being seen in horses with EMS. A cresty neck score of 3 is described as “Crest enlarged and thickened, so fat is deposited more heavily in middle of the neck than towards poll and withers, giving a mounded appearance. Crest fills cupped hand and begins losing side-to-side flexibility.”

2. Neck circumference.

4. Body condition scoring – 8 or 9 on the 9 point Henneke scale is considered obese, 6 and 7 overweight. A 0 to 6 scale is also used, with scores of 4 and 5 being considered overweight and obese - see Body Condition Scoring Video.

Some breeds appear to be more predisposed to EMS than others and there is likely to be a genetic tendency, but developing EMS may depend on certain environmental factors being present, or multiple genes being involved. For example, scurry ponies in active competition tend to have low insulin concentrations, but insulin levels rise when they are not in work, suggesting that exercise helps to prevent them developing EMS.

Breeds adapted to survival when feed is scarce, e.g. cold winters, summer droughts, may be particularly likely to become obese and develop insulin resistance when they have plentiful food all year round.

Native ponies naturally gain weight during the summer when food is abundant and lose weight during the winter, and without these seasonal changes in body condition and insulin sensitivity, horses may become increasingly obese and insulin resistant.

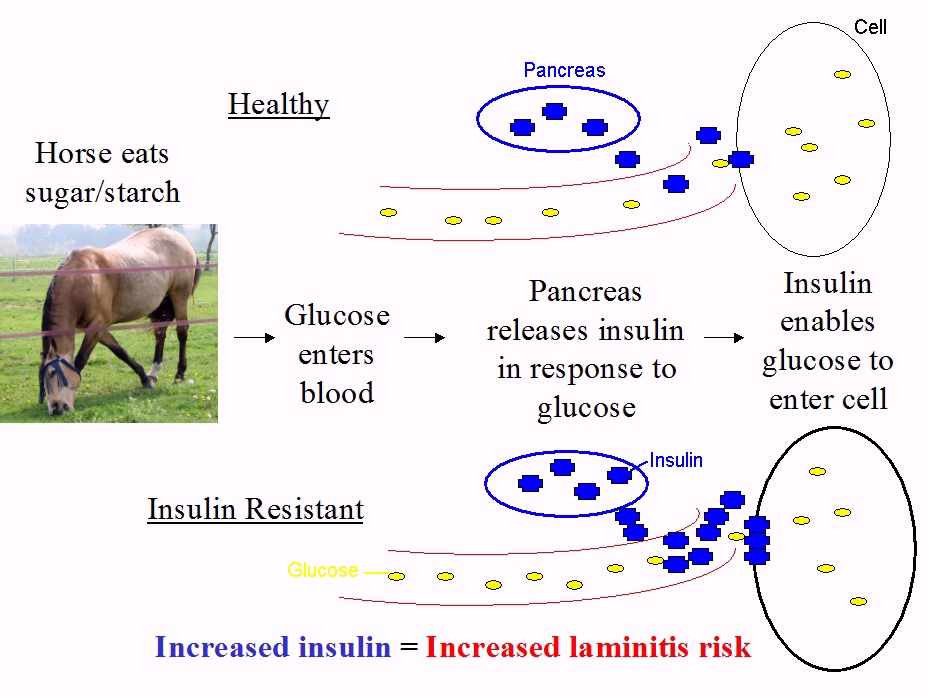

In 2007 it was first discovered that giving healthy horses high levels of insulin caused them to develop laminitis (Asplin et al.). It is hyperinsulinaemia, i.e. above normal levels of insulin, not insulin resistance, that causes endocrinopathic laminitis, but they are often linked, hence the term “insulin dysregulation” is now used to cover both hyperinsulinaemia and insulin resistance.

When a healthy horse eats sugar or starch, blood glucose levels rise and the pancreas releases insulin, which enables glucose to enter insulin sensitive cells, such as muscle.

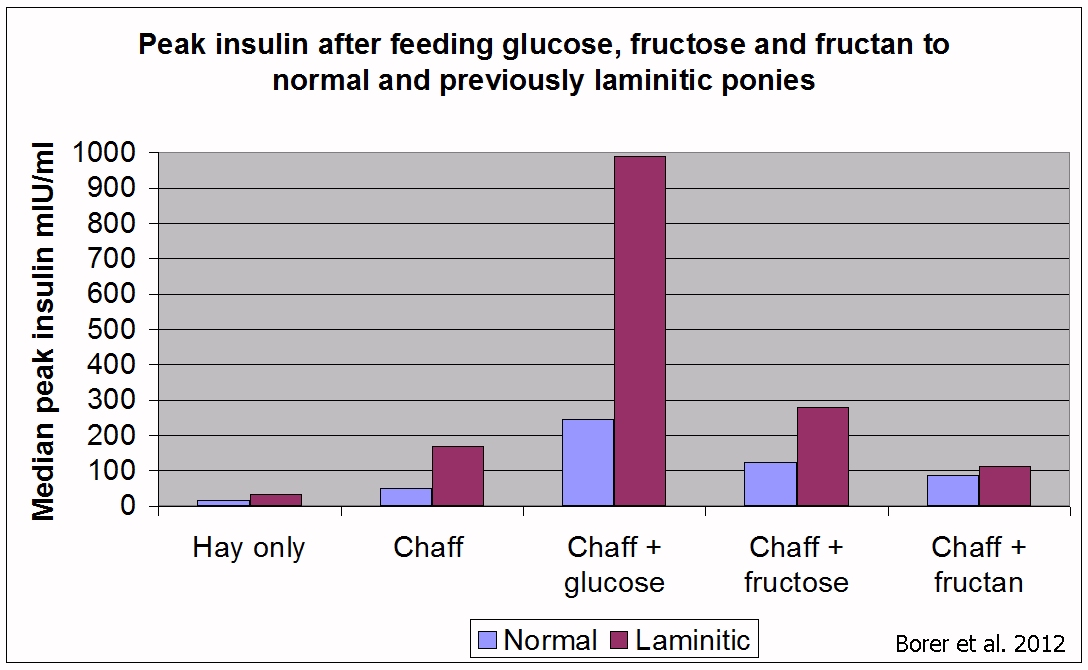

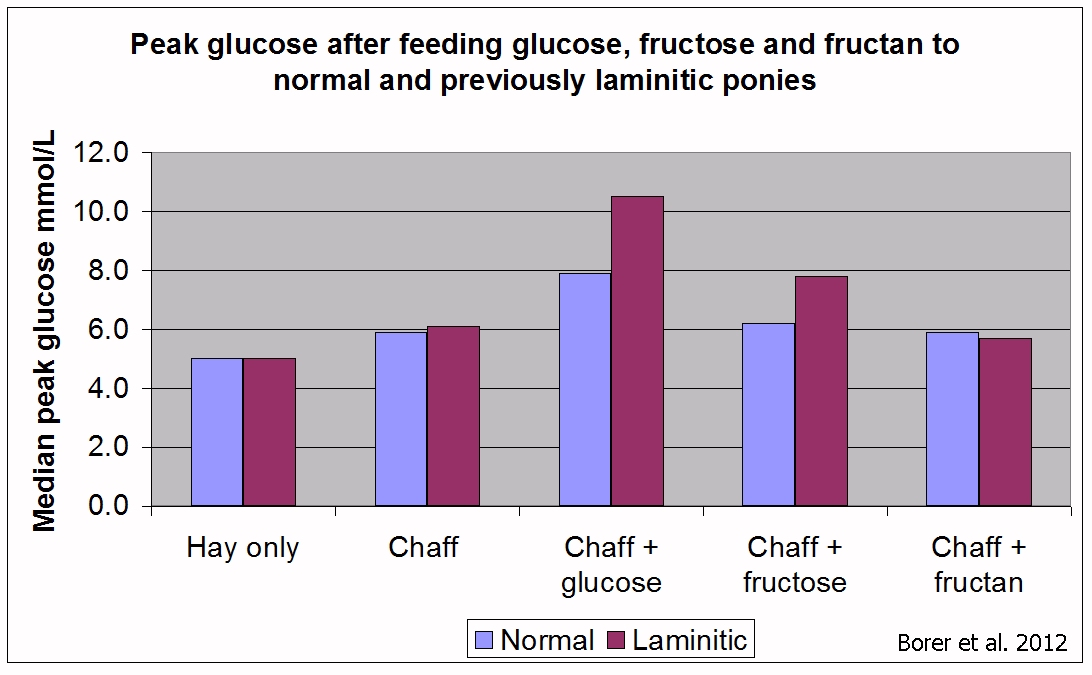

This is illustrated in research by Katie Borer et al. published in 2012. Ponies with no history of laminitis (normal) and ponies with a history of laminitis (laminitic) were fed ad lib soaked Timothy hay and a daily feed of 14% sugar/starch chaff, to which 1 g/kg bodyweight of glucose, fructose and inulin, a type of fructan, were added. The previously laminitic (therefore assumed to have EMS) ponies had a much greater insulin response to glucose than the normal ponies, but their blood glucose levels showed less difference. Note that chaff plus fructan had no greater effect on insulin or glucose than chaff alone.

1. Resting insulin - a single blood sample is tested after the horse has been eating his usual eating hay (note that fasting before a baseline insulin test is no longer recommended for diagnosing EMS; however it may be useful for assessing baseline hyperinsulinaemia in horses with PPID). “Testing horses in the fed state allows for better assessment of insulin dysregulation” (Frank and Tadros 2013), but results may be harder to interpret if sugar/starch levels of the hay are not known. Results above 20-30 mIU/ml are often considered diagnostic of hyperinsulinaemia, but the reference range is specific to the testing laboratory.

If a resting insulin test is normal but the horse has a history of laminitis or is suspected to have EMS, a dynamic test should be carried out.

2. Oral sugar test (OST) – the horse is fasted for at least 6 hours then fed 0.15 ml/kg bodyweight Karo Light corn syrup and blood sampled at 60 and 90 minutes and tested for insulin and glucose. Insulin <45 mIU/ml is considered normal and >60 mIU/ml is considered diagnostic of insulin dysregulation.

More recently it has been suggested that the Oral Sugar Test may be more reliable using the higher dose of 4.5 ml/kg bodyweight Karo Light corn syrup. Originally it was suggested that horses did not need to fast before the higher dose test, but fasting may be recommended by the laboratory/vet. See Karo Light Corn Syrup test for assessment of insulin dysregulation - Liphook Equine Hospital. This test measures the horse’s response to sugar in the diet at the level of the digestive system, pancreas and insulin sensitive tissue.

Current tests are not perfect and diagnosis of EMS should be based on history and clinical signs as well as blood test results.

Diet, weight loss if necessary and exercise are key to preventing and treating EMS.

Diet/weight loss

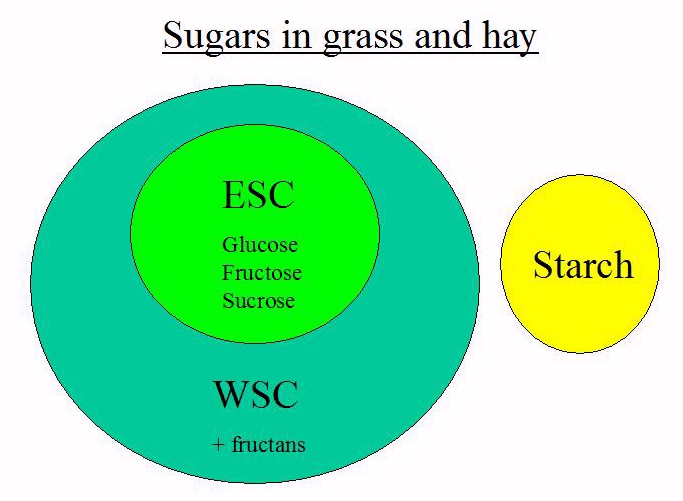

The total combined sugar (ESC) and starch in the diet should be no more than 10% to keep insulin levels low, and if weight loss is required, energy fed will need to be less than energy expended. The severity of the horse’s insulin dysregulation will dictate how strict the sugar/starch restriction needs to be.

|

Ethanol soluble carbohydrate (ESC), which is broadly a term for the simple sugars glucose, fructose and sucrose, and starch, increase blood sugar when digested and therefore increase insulin concentrations. Fructan is fermented in the hind gut to volatile fatty acids (VFAs), and does not increase blood sugar or insulin levels.

Other terms used for carbohydrates found in plants: water soluble carbohydrate (WSC) is the sum of ESC and fructan, non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) is the sum of WSC and starch. Low sugar/starch, high fibre forage e.g. grass hay should form the basis of the diet, ideally analysed for ESC and starch content (Equi-Analytical in the USA analyse ESC, WSC and starch), with protein, minerals, vitamins and essential fatty acids supplemented to meet minimum requirements. |

A typical diet might consist of grass hay plus the recommended amount of a low calorie balancer or mineral supplement, mixed with a low sugar/starch chaff or unmolassed sugar beet, plus salt and linseed (flaxseed).

Low energy feeds should be selected to maximise intake without oversupplying calories. Looking at the analysis of feeds rather than the description is important, e.g. some "high fibre" cubes contain almost 20% combined sugar and starch and would not be suitable for most EMS horses, and feeds claiming to be approved or suitable for laminitics can contain over 14% combined sugar and starch.

Horses with insulin dysregulation that need to gain weight can be fed increased amounts of hay and/or higher energy low sugar/starch feeds such as umolassed sugar beet (beet pulp).

Weight loss is induced by restricting calories eaten and by increasing exercise if the feet are stable. A common suggestion is to feed a horse 1.5% of its ideal, or current, bodyweight (with the diet based on hay with added minerals as described above). If weight loss isn’t seen, this amount may need to be reduced, or ideally a lower energy forage sourced. Feed intake should not go below 1.5% of the horse’s bodyweight without veterinary supervision. Severe calorie restriction can worsen insulin resistance, risk hyperlipaemia and cause stereotypical behaviour.

Access to unrestricted grass commonly triggers laminitis in EMS horses, as sugars increase insulin levels and increased energy intake promotes weight gain. Access to grass should be restricted until insulin sensitivity has returned to normal, with high risk horses perhaps turned out in a dry lot or dirt paddock if the feet are stable to encourage exercise. Many horses that have had EMS can return to pasture once weight has been lost and insulin sensitivity has returned to normal, but may need to have access to grass restricted during high risk times, such as during rapid spring growth or when grass is stressed and cannot grow due to cold weather or drought.

Factors that affect sugars in the grass include:

Sunlight - photosynthesis and sugar production increase with sunlight intensity, so sugar levels will be higher on sunny days and lower on cloudy, overcast and rainy days. Grass growing in direct sunlight will have more sugar than grass growing in the shade.

Time of day – sugar levels peak around late afternoon on a sunny day, then decrease with respiration once the sun sets, so sugars are likely to be lowest in the early morning.

Temperature – night temperatures below 5’C cause sugars to accumulate in the grass, and laminitic horses should avoid grazing during periods of sunny days and cold nights, until warmer nights or overcast weather returns.

|

Stress – grass needs water and nutrients to grow, and drought conditions or poor soil fertility can lead to increased sugar levels.

Grass species – improved species designed for cattle such as rye grass may have higher energy/sugar levels. See www.safergrass.org for more information about sugar levels and grass. Strategies for limiting grazing include short turnout periods (less than 1 hour) or grazing in hand, turnout in a small area, use of a grazing muzzle and putting horses on a track system. Note that when access to grass is restricted, studies have shown that ponies can learn to eat grass quickly, eating almost half of their daily feed requirement in 3 hours of grazing (Longland et al. 2011). |

Regular physical exercise is likely to improve insulin sensitivity and help promote weight loss, and is recommended for EMS horses as long as the feet are stable. The ACVIM consensus statement suggests at least 2-3 sessions of 20-30 minutes of riding or lunging per week, gradually increasing in intensity and duration. Other recommendations for obese horses free of laminitis include riding or lunging 4 to 7 days a week with at least 30 minutes of trot and canter, plus warm up and cool down.

See Exercise

Movement - good or bad?

The ACVIM consensus statement states “Most horses and ponies with EMS can be effectively managed by controlling the horse’s diet, instituting an exercise program, and limiting or eliminating access to pasture.”

Levothyroxine sodium is sometimes given, more commonly in the USA than UK, to induce weight loss.

Metformin is sometimes prescribed for horses that cannot exercise due to laminitis, at the dose of 30 mg/kg bodyweight twice a day. Giving this dose of Metformin before a glucose feed led to reduced glucose and insulin levels compared to controls, but the paper concluded that the potential benefits of giving Metformin to horses on a low NSC diet may be questionable (Rendle et al. 2013).

Whilst various supplements such as magnesium, chromium and cinnamon have been suggested for the management of horses with EMS, currently there is insufficient scientific evidence to support the use of any of these supplements, and where research has been carried out, no or little benefit has been found.

See There are no magic potions!

In theory, yes, EMS is both preventable and reversible. EMS is not a disease, but a collection of factors that increase the risk of endocrinopathic laminitis. Remove these factors (being overweight, having regional fat deposits, having abnormally high insulin levels), and technically the horse no longer has EMS – although some horses with a stronger genetic tendency may always need more careful management than others. The reversal of obesity is likely to have the greatest influence on insulin sensitivity, so make weight loss a priority in overweight horses.

Laminitis, EMS and PPID

Laminitis and the Feet

Testing Insulin

Diet for horses with laminitis/EMS/PPID

Management Strategies for EMS/Insulin Resistance

Case study: Rosie

Equine Endocrinology Group - Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) 2018

Durham AE, Frank N, McGowan CM, Menzies-Gow NJ, Roelfsema E, Vervuert I, Feige K, Fey K

ECEIM consensus statement on equine metabolic syndrome

J Vet Intern Med. Published online 6 Feb 2019. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15423

Morgan R, Keen J, McGowan C

Equine metabolic syndrome

Veterinary Record Aug 2015;177:173-179 doi:10.1136/vr.103226

References:

Asplin KE, Sillence MN, Pollitt CC, McGowan CM

Induction of laminitis by prolonged hyperinsulinaemia in clinically normal ponies

The Veterinary Journal Vol 174, Issue 3, November 2007, Pages 530-535

Borer KE, Bailey SR, Menzies-Gow NJ, Harris PA, Elliott J

Effect of feeding glucose, fructose, and inulin on blood glucose and insulin concentrations in normal ponies and those predisposed to laminitis.

J Anim Sci. 2012 Sep;90(9):3003-11

Carter RA, Geor RJ, Burton Staniar W, Cubitt TA, Harris PA

Apparent adiposity assessed by standardised scoring systems and morphometric measurements in horses and ponies

Vet J. 2009 Feb;179(2):204-10

Carter RA, McCutcheon LJ, George LA, Smith TL, Frank N, Geor RJ

Effects of diet-induced weight gain on insulin sensitivity and plasma hormone and lipid concentrations in horses

Am J Vet Res. 2009 Oct;70(10):1250-8

Frank N, Geor RJ, Bailey SR, Durham AE, Johnson PJ

Equine Metabolic Syndrome - ACVIM Consensus Statement

J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:467–475

Frank N, Tadros E M

Insulin dysregulation

Equine Veterinary Journal Volume 46, Issue 1, pages 103–112, January 2014

A Longland, J Ince, P Harris

Estimation of pasture intake by ponies from liveweight change during six weeks at pasture

J Equine Veterinary Science May–June 2011 Volume 31, Issues 5-6, Pages 275–276

Quinn RW, Burk AO, Hartsock TG, Petersen ED, Whitley NC, Treiber KH, Boston RC

Insulin Sensitivity in Thoroughbred Geldings: Effect of Weight Gain, Diet, and Exercise on Insulin Sensitivity in Thoroughbred Geldings

Journal of Equine Veterinary Science , Volume 28 , Issue 12 , 728 - 738

Rendle DI, Rutledge F, Hughes KJ, Heller J, Durham AE

Effects of metformin hydrochloride on blood glucose and insulin responses to oral dextrose in horses

Equine Vet J. 2013 Nov;45(6):751-754

Photos: thanks to Kat, Liz and Selina for use of photos.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed