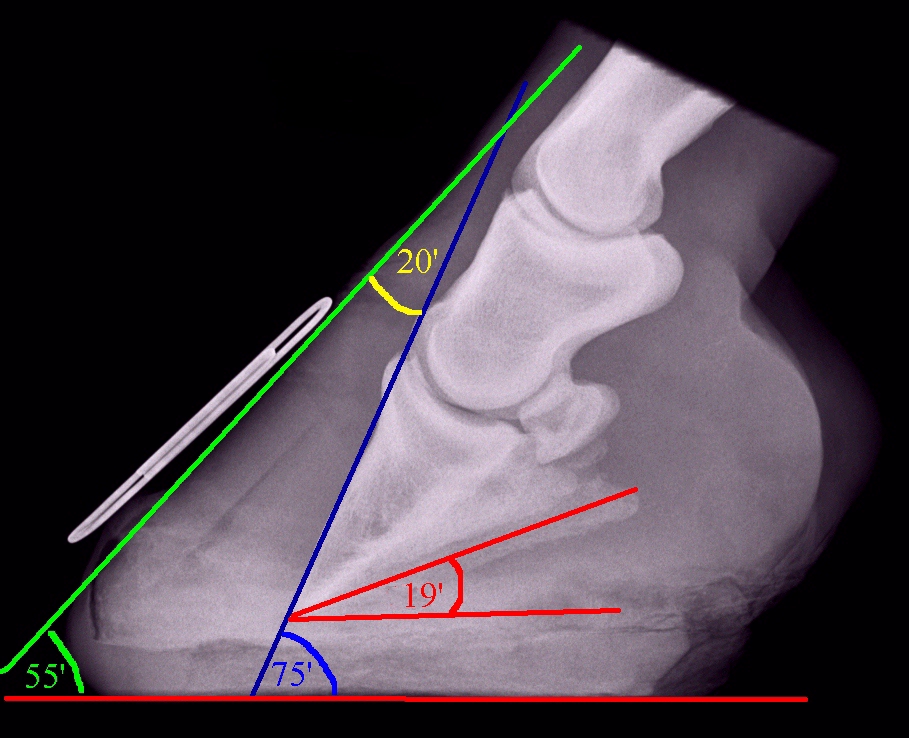

| Q. What is meant by rotation? A. We generally talk about 2 angles following laminitis: The palmar (or plantar) angle - in red - is the angle between the solar margin (bottom) of the pedal bone (P3) and the ground. The dorsal angle or angle/degree of rotation - in yellow - is the angle between the hoof wall at the toe (green) and the dorsal (front) aspect of the pedal bone (blue). In Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot (p 341) Pete Ramey suggests that what is often called rotation is simply flare, i.e. separation of the hoof wall and the pedal bone. The pedal bone hasn't gone anywhere, it hasn't rotated, but the hoof wall has been displaced (by the stretching of the laminae/laminar wedge). This can be corrected by setting up the pedal bone as it would be if the hoof wall was in the correct place, then growing a new properly connected wall down from the coronary band. | Don't let the numbers alarm you - rotation of over 30 degrees can be corrected - see Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol. |

| What other measurements might help assess changes after laminitis? A. In Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol, Debra Taylor et al. measured the degree of rotation and palmar angle (above), and also:

|

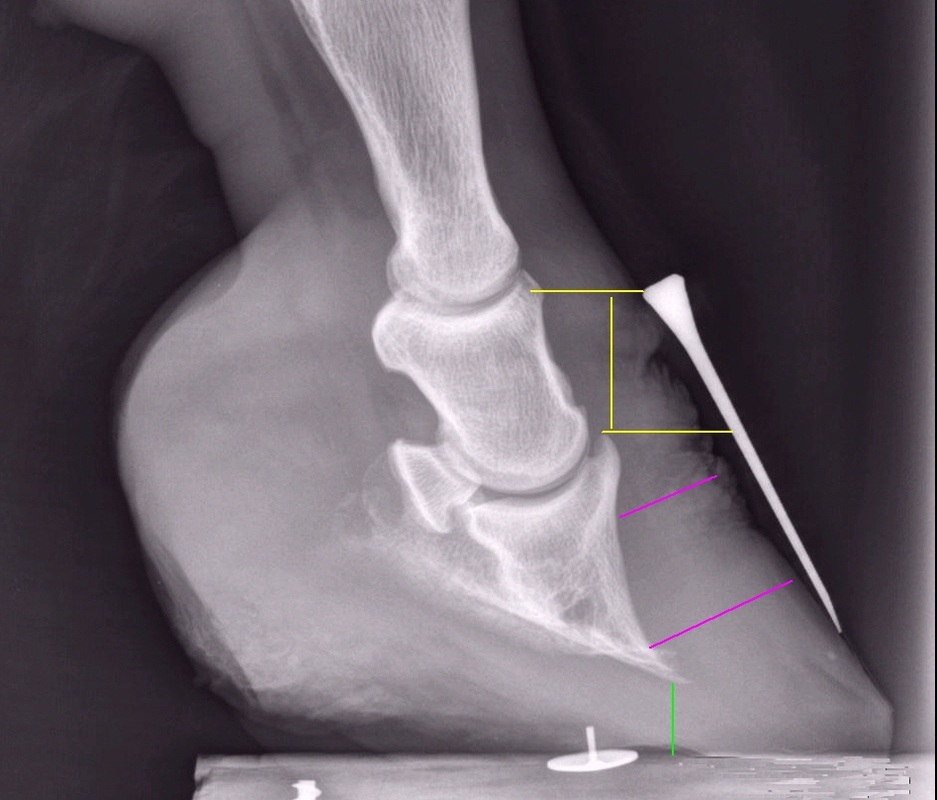

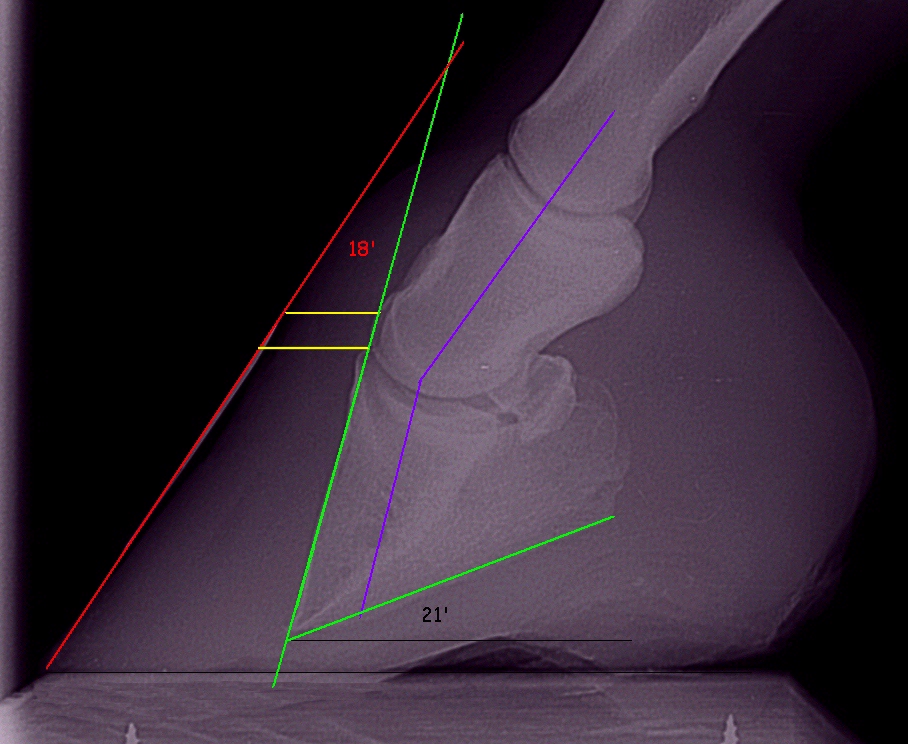

| Q. Can rotation always be corrected? A. In most cases rotation can and should be corrected at the earliest opportunity, it's a case of trimming the hoof capsule back in alignment with the pedal bone. Sorrel's left fore had a palmar angle of around 21 degrees and a dorsal angle of around 18 degrees, with phalangeal/bony rotation (the bones were out of alignment - purple line) - this rotation was probably long-standing. Within 3 trims her feet had been realigned, and within 8 months she was back in work - see her story here. On p 350 of Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot, Pete Ramey says that as long as the pedal bone hasn't been significantly remodelled, he is pretty confident that he can rehabilitate 20 degree hoof capsule rotations, most sinkers and even most "sole penetrations". |

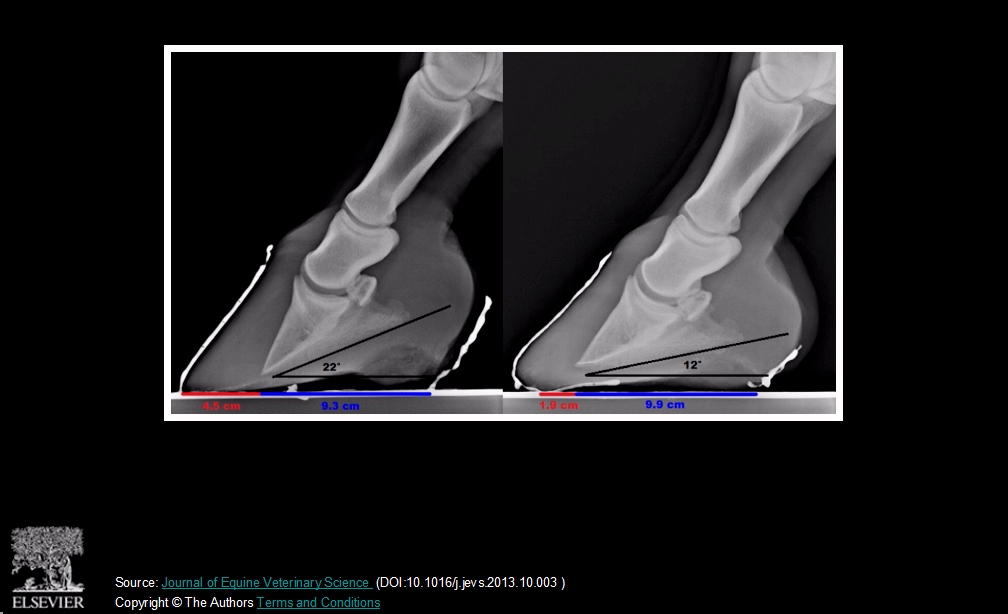

(Above) In the 2014 paper, Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol (without doubt one of the most important papers published regarding laminitis rehabilitation), Debra Taylor et al. returned 14 of 14 laminitic horses with rotation ≥5° (6 had >11.5° of rotation) to their pre-laminitis level of soundness by the time of the endpoint radiographic evaluation.

Q. Even rotation of 30 degrees or more?

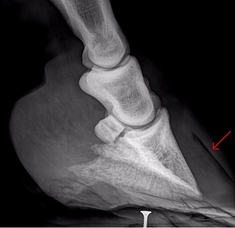

A. Yes, depending on the individual circumstances. Besides, at some point, talking about the size of an angle of rotation may become rather pointless - what would the angle of rotation be on Cedar's left fore before his realigning trim below (possible position of the pedal bone marked in green)? After 3 months his realigning trim was pretty much complete, and x-rays a month later confirmed this, although there was still distal descent which would hopefully correct with time. See photos of Cedar's rehab here.

A. Yes, depending on the individual circumstances. Besides, at some point, talking about the size of an angle of rotation may become rather pointless - what would the angle of rotation be on Cedar's left fore before his realigning trim below (possible position of the pedal bone marked in green)? After 3 months his realigning trim was pretty much complete, and x-rays a month later confirmed this, although there was still distal descent which would hopefully correct with time. See photos of Cedar's rehab here.

In Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol, the maximum pre-treatment palmar angle was 31 degrees, and the maximum dorsal angle (degrees of rotation) was 29 degrees. All horses returned to their pre-laminitis level of soundness.

Q. What happens if rotation isn't corrected?

A. Whilst the foot is not correctly aligned there is likely to be an increased risk of rotation, sinking, cellular damage and bone loss.

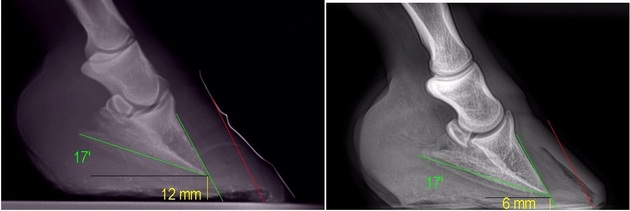

The x-rays above are of the same foot taken two months apart. The toes have been brought back slightly but the heels have remained excessively high with a palmar angle of around 17 degrees. After two months there is less sole depth beneath the tip of the pedal bone, and a gas pocket suggesting total separation of the laminae is now evident. Luckily this horse was kept confined and his feet well supported and made a good recovery, but leaving the heels high could have caused further sinking and rotation, and his recovery could almost certainly have been much quicker if his feet had been realigned as soon as laminitis was diagnosed.

The x-rays above are of the same foot taken two months apart. The toes have been brought back slightly but the heels have remained excessively high with a palmar angle of around 17 degrees. After two months there is less sole depth beneath the tip of the pedal bone, and a gas pocket suggesting total separation of the laminae is now evident. Luckily this horse was kept confined and his feet well supported and made a good recovery, but leaving the heels high could have caused further sinking and rotation, and his recovery could almost certainly have been much quicker if his feet had been realigned as soon as laminitis was diagnosed.

| Following rotation, if the heels are left high and the palmar angle remains large, the live cells of the sole can be compressed underneath the pedal bone, leading to bone loss (osteolysis) and cell death. This in turn can lead to abscessing, penetration of the pedal bone through the sole, or incurable sepsis. See The circumflex artery and solar corium necrosis. Left: long-term uncorrected rotation with heels being left too high led to considerable bone loss for this pony. |

Insulin resistant pony Mary had been regularly trimmed by a farrier who left her heels too high. When Jenny Edwards of All Natural Horse Care rescued Mary she had dorsal rotation of around 24 degrees, palmar angles of around 19 degrees, considerable sinking, and bone loss and remodelling (ski tip) of the pedal bone. A realigning trim and boots and pads made Mary much more comfortable and she was soon trotting happily. Her story here includes an excellent video showing her increase in comfort from wearing boots and pads despite being on soft sand.

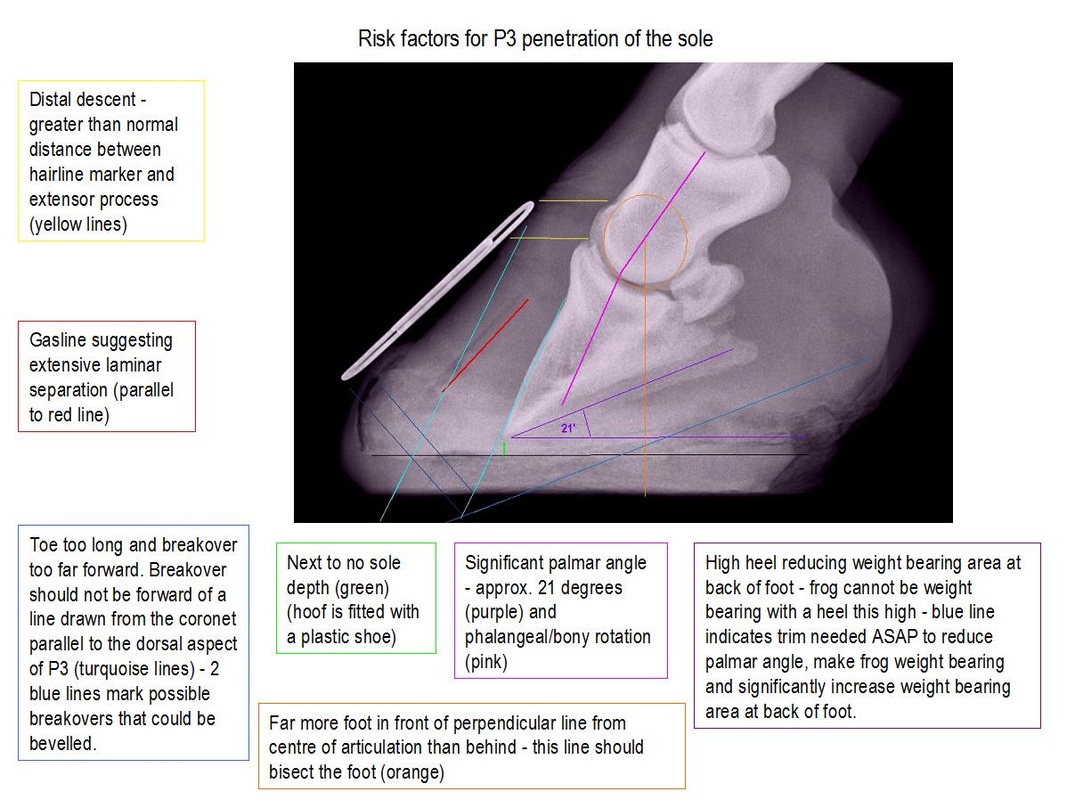

Q. How can the risk of penetration of the sole be reduced?

A. By carrying out a correct realigning trim at the earliest opportunity and supporting the feet.

See Solar penetration. http://www.thelaminitissite.org/feet-faq--articles/solar-penetration

A. By carrying out a correct realigning trim at the earliest opportunity and supporting the feet.

See Solar penetration. http://www.thelaminitissite.org/feet-faq--articles/solar-penetration

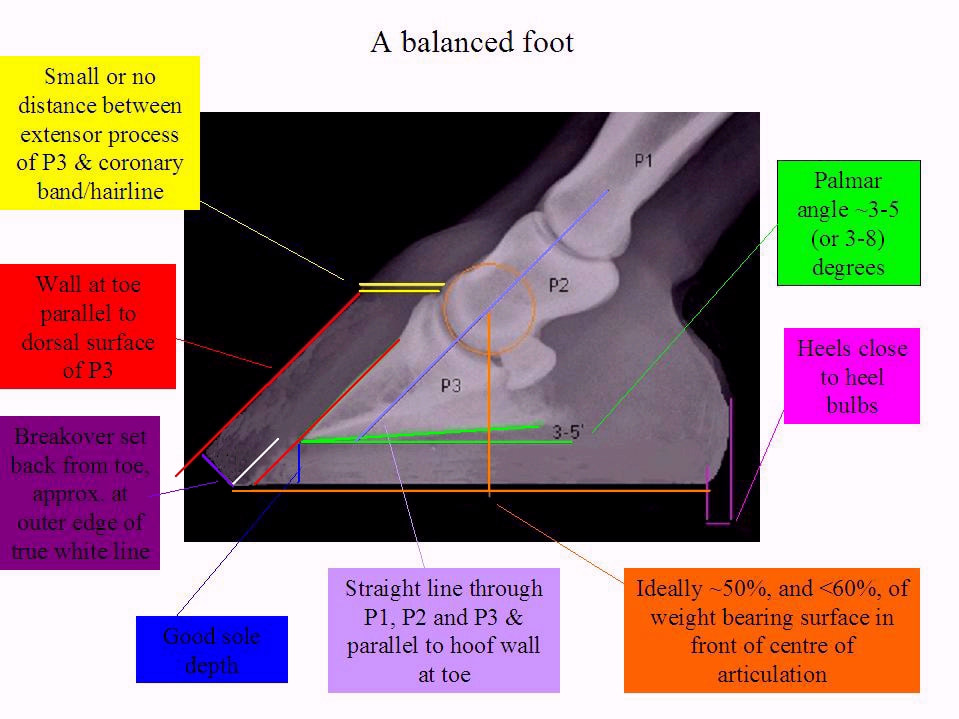

Q. How should a correctly aligned foot look in an x-ray?

Q. Can a horse recover if the pedal bone penetrates the sole?

A. Yes. But it takes dedication. See Solar penetration. http://www.thelaminitissite.org/feet-faq--articles/solar-penetration

Read Paige Poss' inspiring story about Druid.

Druid had rotation (around 18 degrees dorsal rotation in one x-ray) which led to penetration of the pedal (coffin) bones in all four feet. He could hardly stand at first, had bed sores, gastric ulcers and weeks of abscessing. However, within 5 months he was able to wander around outside, x-rays at 6 months showed realignment of the feet, and within 10 months he was comfortable on gravel, trotting, and starting to be ridden again.

Blossom, a Clydesdale, recovered from rotation and penetration following laminitis seemingly caused by a liver infection, with a barefoot trim, daily soaks and boots and pads, thanks to Andrew Bowe at www.barehoofcare.com. Andrew also helped Whisky recover from penetration in all four feet. And Jenny Wren.

A. Yes. But it takes dedication. See Solar penetration. http://www.thelaminitissite.org/feet-faq--articles/solar-penetration

Read Paige Poss' inspiring story about Druid.

Druid had rotation (around 18 degrees dorsal rotation in one x-ray) which led to penetration of the pedal (coffin) bones in all four feet. He could hardly stand at first, had bed sores, gastric ulcers and weeks of abscessing. However, within 5 months he was able to wander around outside, x-rays at 6 months showed realignment of the feet, and within 10 months he was comfortable on gravel, trotting, and starting to be ridden again.

Blossom, a Clydesdale, recovered from rotation and penetration following laminitis seemingly caused by a liver infection, with a barefoot trim, daily soaks and boots and pads, thanks to Andrew Bowe at www.barehoofcare.com. Andrew also helped Whisky recover from penetration in all four feet. And Jenny Wren.

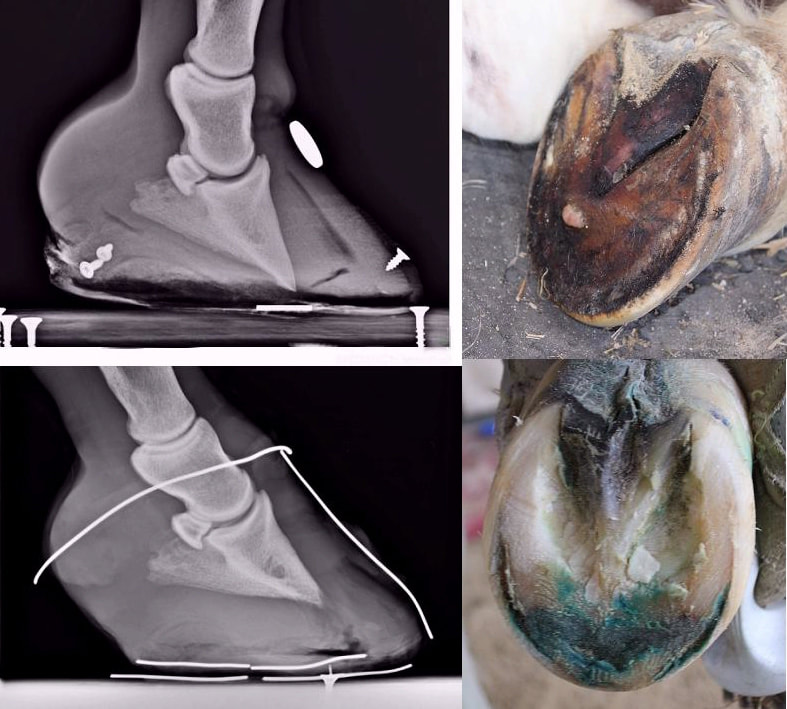

Above: This mare's right fore pedal bone penetrated her sole around 3 months after she developed sepsis-related laminitis due to retaining placenta after foaling, and the left fore almost penetrated.

Top - a SoleMate pad had been fitted with a hole beneath the tip of the pedal bone which the pedal bone sank into. Realigning trimming had not been carried out, the toes were too long with force being exerted on the toe to the outside of the large area of separation (black gas pocket) that ran the full length of the laminae, and the heels were too high.

Bottom - 3 months later (the x-ray was taken pre-trim and 4 weeks beyond the recommended next trim date) the foot is almost fully realigned (and was fully realigned at the next trim), and the sole depth has increased significantly (and was reduced in the next trim - there is too much sole depth here). The area of separation (black gas pocket) has almost grown down past P3, and was mostly removed at the next trim. An old abscess hole is seen beneath the tip of P3, but no exudate was found. The tip of P3 shows remodeling and damage. Options for supporting the foot and preventing infection had been limited during the rehabilitation.

Top - a SoleMate pad had been fitted with a hole beneath the tip of the pedal bone which the pedal bone sank into. Realigning trimming had not been carried out, the toes were too long with force being exerted on the toe to the outside of the large area of separation (black gas pocket) that ran the full length of the laminae, and the heels were too high.

Bottom - 3 months later (the x-ray was taken pre-trim and 4 weeks beyond the recommended next trim date) the foot is almost fully realigned (and was fully realigned at the next trim), and the sole depth has increased significantly (and was reduced in the next trim - there is too much sole depth here). The area of separation (black gas pocket) has almost grown down past P3, and was mostly removed at the next trim. An old abscess hole is seen beneath the tip of P3, but no exudate was found. The tip of P3 shows remodeling and damage. Options for supporting the foot and preventing infection had been limited during the rehabilitation.

Q. Can the hoof wall completely detach from the pedal bone?

A. Most cases of laminitis are endocrine, that is they are caused by EMS/PPID. Recent research has shown that with insulin-induced laminitis, the secondary epidermal laminae become longer and narrower - they stretch. Katie Asplin found that there was minimal basement separation in ponies, and Melody de Laat also found less damage to the basement membrane in horses with insulin-induced laminitis than those with SIRS laminitis. So it would appear that there is stretching and weakening of the laminae, but not necessarily complete separation.

A. Most cases of laminitis are endocrine, that is they are caused by EMS/PPID. Recent research has shown that with insulin-induced laminitis, the secondary epidermal laminae become longer and narrower - they stretch. Katie Asplin found that there was minimal basement separation in ponies, and Melody de Laat also found less damage to the basement membrane in horses with insulin-induced laminitis than those with SIRS laminitis. So it would appear that there is stretching and weakening of the laminae, but not necessarily complete separation.

| The hoof wall growth immediately beneath the coronet is usually connected to and parallel to the pedal bone. A change of angle where the hoof wall flares out is likely to indicate stretching of the laminae and formation of a laminar wedge. This pony (right) had laminitis in October due to (at that time) undiagnosed PPID. He made a full recovery and was soon back in work. He never had x-rays taken, and had regular "normal" barefoot trims. |

When extensive laminar separation has occurred, a black gas pocket can often be seen on a lateromedial x-ray between the hoof wall and laminar wedge. When this is seen, the foot should be fully supported to prevent further mechanical failure of the laminae and further movement of P3 - see Care & Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot p 261.

Once a correct realigning trim has been carried out and a new hoof grown down from the coronet, even a horse with significant gas pockets should be able to return to work, as was the case with Homer, above.

Once a correct realigning trim has been carried out and a new hoof grown down from the coronet, even a horse with significant gas pockets should be able to return to work, as was the case with Homer, above.

Q. Is it possible to tell whether damage due to laminitis is recent or old?

In Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol, horses were considered to have chronic laminitis (presumably suggesting long-standing damage) if they had hoof rings that were wider at the heel than at the toe, and/or if their pedal bones showed remodelling, e.g. a ski tip, when x-rayed. Horses that had neither of these were considered to have acute laminitis (presumably suggesting recent damage)

On p 341 of Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot, Pete Ramey suggests that it usually takes months to form a laminar wedge that is 2 cm thick at ground level, so when a thick laminar wedge is seen, the rotation is not new, and the original laminitic episode could have happened years ago.

In Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol, horses were considered to have chronic laminitis (presumably suggesting long-standing damage) if they had hoof rings that were wider at the heel than at the toe, and/or if their pedal bones showed remodelling, e.g. a ski tip, when x-rayed. Horses that had neither of these were considered to have acute laminitis (presumably suggesting recent damage)

On p 341 of Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot, Pete Ramey suggests that it usually takes months to form a laminar wedge that is 2 cm thick at ground level, so when a thick laminar wedge is seen, the rotation is not new, and the original laminitic episode could have happened years ago.

This pony (above) appears to have a change of angle in the hoof wall just below the coronet, a large laminar wedge and divergent hoof rings almost to ground level, suggesting long-term chronic laminitis. X-rays showed remodelling of the pedal bone in both fores, confirming this.

Q. Does a horse being overweight affect the severity of laminitic damage?

A. This seems quite likely. Melody de Laat recorded that all 4 feet of the heavier horses had laminar damage, but only 3/4 feet in the lightest horse in her 2011 RIRDC report Insulin-Induced Laminitis.

A. This seems quite likely. Melody de Laat recorded that all 4 feet of the heavier horses had laminar damage, but only 3/4 feet in the lightest horse in her 2011 RIRDC report Insulin-Induced Laminitis.

Q. Any more successful rehabilitation case studies?

A. Here are a few:

Sophie - All Natural Horse Care

Missy - All Natural Horse Care

Pip - All Natural Horse Care

Oscar - www.barehoofcare.com

Charlie - www.barehoofcare.com

Glynn - www.naturalhorseworld.com

And already mentioned above:

Blossom - www.barehoofcare.com

Whisky - www.barehoofcare.com

A. Here are a few:

Sophie - All Natural Horse Care

Missy - All Natural Horse Care

Pip - All Natural Horse Care

Oscar - www.barehoofcare.com

Charlie - www.barehoofcare.com

Glynn - www.naturalhorseworld.com

And already mentioned above:

Blossom - www.barehoofcare.com

Whisky - www.barehoofcare.com

References:

Asplin KE, Patterson-Kane JC, Sillence MN, Pollitt CC, Mc Gowan CM

Histopathology of insulin-induced laminitis in ponies

Equine Vet J. 2010 Nov;42(8):700-6 (PubMed)

de Laat M, Sillence M, McGowan C, Pollitt C

Insulin-Induced Laminitis - An investigation of the disease mechanism in horses

RIRDC Dec 2011

Taylor D, Sperandeo A, Schumacher J, Passler T, Wooldridge A, Bell R, Cooner A, Guidry L, Matz-Creel H, Ramey I, Ramey P

Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol

JEVS published online 05 Feb 2014

Pete Ramey - Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot

More Information:

Hoof Rehabilitation Protocol - Debra Taylor, Ivy Ramey, Pete Ramey

Taylor D, Sperandeo A, Bell R, Passler T, Ramey I, Ramey P

Hoof Rehabilitation and Restoration of Soundness in Obese Laminitic Horses

AAEP

Asplin KE, Patterson-Kane JC, Sillence MN, Pollitt CC, Mc Gowan CM

Histopathology of insulin-induced laminitis in ponies

Equine Vet J. 2010 Nov;42(8):700-6 (PubMed)

de Laat M, Sillence M, McGowan C, Pollitt C

Insulin-Induced Laminitis - An investigation of the disease mechanism in horses

RIRDC Dec 2011

Taylor D, Sperandeo A, Schumacher J, Passler T, Wooldridge A, Bell R, Cooner A, Guidry L, Matz-Creel H, Ramey I, Ramey P

Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol

JEVS published online 05 Feb 2014

Pete Ramey - Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot

More Information:

Hoof Rehabilitation Protocol - Debra Taylor, Ivy Ramey, Pete Ramey

Taylor D, Sperandeo A, Bell R, Passler T, Ramey I, Ramey P

Hoof Rehabilitation and Restoration of Soundness in Obese Laminitic Horses

AAEP

RSS Feed

RSS Feed