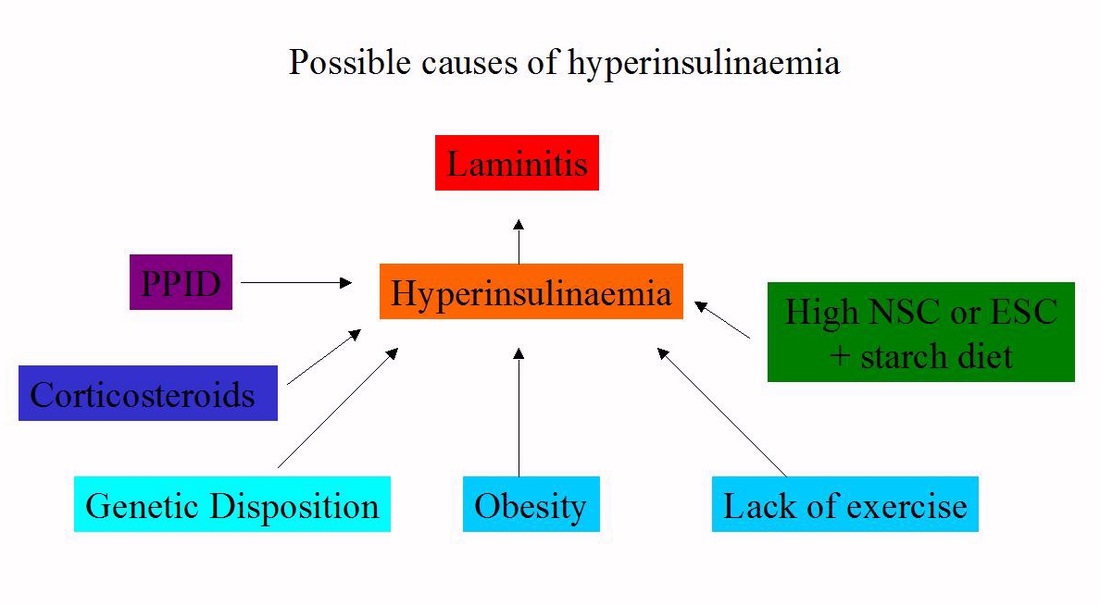

| Hyperinsulinaemia - above normal levels of insulin - causes endocrine laminitis. Diagnosis Testing insulin levels forms part of the diagnosis of Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS), and gives information about insulin dysregulation and laminitis risk. All horses suspected of having PPID should also have insulin tested to assess their laminitis risk. There are currently no perfect tests for diagnosing EMS or insulin dysregulation. The pros and cons of the tests currently available "in the field" are discussed below. |

Resting insulin tests

This is the easiest test to carry out and involves taking a single sample of blood to measure the amount of insulin in the horse's blood at that moment in time. It can be either:

1. Fasting resting insulin - the horse is fasted for at least 6 hours before the blood is collected.

This test has a high false negative rate (around 2/3 of horses with insulin dysregulation have a normal fasting insulin result), so a normal test result does not rule out EMS, and a dynamic or non-fasted resting test should follow a normal fasting insulin test if a horse is suspected of having insulin dysregulation. If a horse gets stressed from having food withheld - this may be a particular problem on a yard where other horses are being fed and the horse being tested isn't - this could falsely increase the result.

Interpretation:

Results above the laboratory cut-off are diagnostic of hyperinsulinaemia.

Whilst a cut off of 20 mIU/l is often used, reference ranges for insulin are laboratory specific - the reference range given by the testing laboratory should be used. Note that different assays, e.g. RIA v CIA, may produce different results meaning that results cannot be compared.

Liphook Equine Hospital (Immulite CIA) - 20 mIU/l and above is considered above normal and diagnostic of hyperinsulinaemia.

Reference ranges for insulin may be breed specific, therefore a cut-off of 20 µIU/ml may not be appropriate for all breeds.

TLS comment: due to the high number of false negatives, this test is probably only worth doing if a horse obviously has EMS/insulin dysregulation (e.g. history of laminitis, overweight, fat pads), but the test is diagnostic, accepted by vets, and good for monitoring progress when positive.

2. Non-fasting resting insulin - the horse eats hay or grass but no bucket feed in the 6 hours before the blood is collected.

Allowing the horse access to food before the resting insulin test measures the horse's insulin response to its normal diet. But if the amount of sugar in the diet isn't known, this adds uncertainty to the test and makes a borderline result more difficult to interpret.

This was the test recommended by vets/researchers until a few years ago, generally using a cut off of 30 uIU/ml (rather than the 20 uIU/ml cut off used for the fasting test). Presumably because hay can have differing sugar levels, vets/researchers have decided this test isn't as accurate as the fasting test. However, it's unlikely hay is going to push a "normal" horse over a cut-off of 30 uIU/ml, or even 20 uIU/ml.

The ECIR group recommends that low sugar/soaked hay is in front of the horse at all times before the test - DDT Diagnosis of PPID and IR.

TLS comment: there seem to be less false negatives with this test and it gives an accurate reflection of the horse's actual day to day insulin levels, but there may be a grey area around the cut-off due to unknown sugar levels in the hay/grass. With no fasting and no abnormally raised insulin levels involved, it is safe and is probably the test a horse would choose!

This is the easiest test to carry out and involves taking a single sample of blood to measure the amount of insulin in the horse's blood at that moment in time. It can be either:

1. Fasting resting insulin - the horse is fasted for at least 6 hours before the blood is collected.

This test has a high false negative rate (around 2/3 of horses with insulin dysregulation have a normal fasting insulin result), so a normal test result does not rule out EMS, and a dynamic or non-fasted resting test should follow a normal fasting insulin test if a horse is suspected of having insulin dysregulation. If a horse gets stressed from having food withheld - this may be a particular problem on a yard where other horses are being fed and the horse being tested isn't - this could falsely increase the result.

Interpretation:

Results above the laboratory cut-off are diagnostic of hyperinsulinaemia.

Whilst a cut off of 20 mIU/l is often used, reference ranges for insulin are laboratory specific - the reference range given by the testing laboratory should be used. Note that different assays, e.g. RIA v CIA, may produce different results meaning that results cannot be compared.

Liphook Equine Hospital (Immulite CIA) - 20 mIU/l and above is considered above normal and diagnostic of hyperinsulinaemia.

Reference ranges for insulin may be breed specific, therefore a cut-off of 20 µIU/ml may not be appropriate for all breeds.

TLS comment: due to the high number of false negatives, this test is probably only worth doing if a horse obviously has EMS/insulin dysregulation (e.g. history of laminitis, overweight, fat pads), but the test is diagnostic, accepted by vets, and good for monitoring progress when positive.

2. Non-fasting resting insulin - the horse eats hay or grass but no bucket feed in the 6 hours before the blood is collected.

Allowing the horse access to food before the resting insulin test measures the horse's insulin response to its normal diet. But if the amount of sugar in the diet isn't known, this adds uncertainty to the test and makes a borderline result more difficult to interpret.

This was the test recommended by vets/researchers until a few years ago, generally using a cut off of 30 uIU/ml (rather than the 20 uIU/ml cut off used for the fasting test). Presumably because hay can have differing sugar levels, vets/researchers have decided this test isn't as accurate as the fasting test. However, it's unlikely hay is going to push a "normal" horse over a cut-off of 30 uIU/ml, or even 20 uIU/ml.

The ECIR group recommends that low sugar/soaked hay is in front of the horse at all times before the test - DDT Diagnosis of PPID and IR.

TLS comment: there seem to be less false negatives with this test and it gives an accurate reflection of the horse's actual day to day insulin levels, but there may be a grey area around the cut-off due to unknown sugar levels in the hay/grass. With no fasting and no abnormally raised insulin levels involved, it is safe and is probably the test a horse would choose!

Dynamic insulin tests

This measures the horse's insulin response after eating glucose/sugar - a high result suggests insulin dysregulation, therefore it should be a good test for determining which horses are at higher risk of getting laminitis. However dynamic tests can also give false negative results - Dianne McFarlane suggested that half the horses she tested that she pretty much knew had EMS tested negative - Is it PPID or is it EMS?

If a baseline (resting) sample is taken before the glucose is fed, the increase in insulin as a result of eating the glucose can be measured.

If insulin is only measured after the horse has eaten the glucose, it isn't possible to know how much the insulin increased as a result of eating the glucose - the horse could have had an above normal insulin concentration even after fasting for several hours.

A dynamic insulin test can be either:

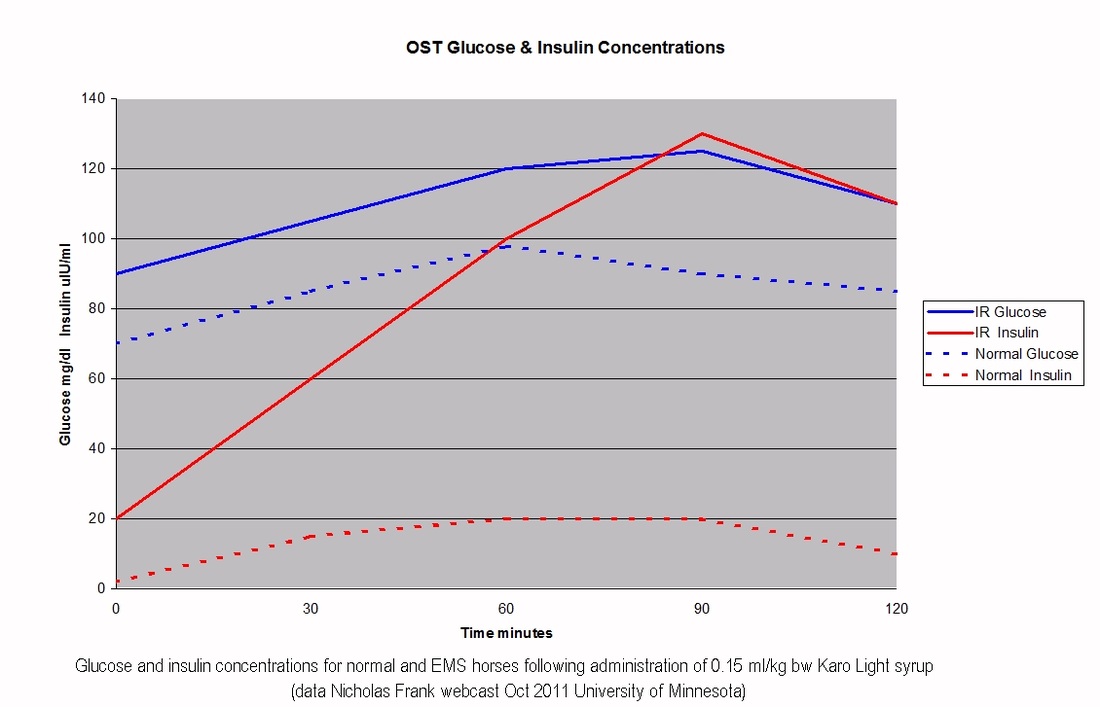

3. Oral Sugar Test (OST) - this uses 0.15 ml/kg bodyweight Karo Light corn syrup, which gives around 75 g sugar to a 500 kg horse, which isn't totally unlike a horse eating grass - say a 500 kg horse eats 2.5% of his bodyweight in 12% ESC/starch grass (fructans don't appear to increase insulin, grass doesn't tend to have more than around 12% simple sugars, after that simple sugars are turned into fructans), that would be 1500 g sugar, over 16 hours grazing, so 94 g sugar/hr of grazing. So 75 g in a few minutes is still likely to be far more than a horse can eat naturally, but it's a lot better than the in-feed glucose test. All research done to validate this test (and the in-feed glucose test) has been done with the horse fasting for at least 6 hours beforehand, so for these dynamic tests the horse should be fasted for accurate interpretation.

Recently (2017) it has been suggested that a higher dose Oral Sugar Test can be carried out without the horse having to be fasted beforehand, using 4.5 ml/kg bodyweight Karo Light corn syrup. See Karo Light Corn Syrup test for assessment of insulin dysregulation - Liphook Equine Hospital.

This measures the horse's insulin response after eating glucose/sugar - a high result suggests insulin dysregulation, therefore it should be a good test for determining which horses are at higher risk of getting laminitis. However dynamic tests can also give false negative results - Dianne McFarlane suggested that half the horses she tested that she pretty much knew had EMS tested negative - Is it PPID or is it EMS?

If a baseline (resting) sample is taken before the glucose is fed, the increase in insulin as a result of eating the glucose can be measured.

If insulin is only measured after the horse has eaten the glucose, it isn't possible to know how much the insulin increased as a result of eating the glucose - the horse could have had an above normal insulin concentration even after fasting for several hours.

A dynamic insulin test can be either:

3. Oral Sugar Test (OST) - this uses 0.15 ml/kg bodyweight Karo Light corn syrup, which gives around 75 g sugar to a 500 kg horse, which isn't totally unlike a horse eating grass - say a 500 kg horse eats 2.5% of his bodyweight in 12% ESC/starch grass (fructans don't appear to increase insulin, grass doesn't tend to have more than around 12% simple sugars, after that simple sugars are turned into fructans), that would be 1500 g sugar, over 16 hours grazing, so 94 g sugar/hr of grazing. So 75 g in a few minutes is still likely to be far more than a horse can eat naturally, but it's a lot better than the in-feed glucose test. All research done to validate this test (and the in-feed glucose test) has been done with the horse fasting for at least 6 hours beforehand, so for these dynamic tests the horse should be fasted for accurate interpretation.

Recently (2017) it has been suggested that a higher dose Oral Sugar Test can be carried out without the horse having to be fasted beforehand, using 4.5 ml/kg bodyweight Karo Light corn syrup. See Karo Light Corn Syrup test for assessment of insulin dysregulation - Liphook Equine Hospital.

4. In-feed Glucose Challenge

The in-feed glucose challenge uses a large amount of glucose (either 1 g or 0.5 g per kg bodyweight, so 500 or 250 g for a 500 kg horse), an amount that a horse could not eat in its natural diet. One problem with this is that glucose enters the blood through glucose transporters, which can become saturated. When a horse is used to having a lot of sugar in its diet, it will increase the number of glucose transporters (this has been proven by feeding increasing amounts of starch). But when a horse is usually on a low sugar diet and is suddenly fed a huge amount of glucose, a large amount of this may be unable to be absorbed in the small intestine and will be carried through to the hind gut. So the number of glucose transporters will have an effect on the insulin result. And the test could potentially cause diarrhoea, gas and colic - we have had reports of diarrhoea following the test using 1g/kg bw glucose.

As can be seen from the paragraph above, this amount of glucose is FAR more than a horse can possibly eat naturally. So although this test has been used in research to distinguish horses with EMS from horses without EMS, all it really tells you is how much insulin your horse will produce if given a massive amount of sugar that it couldn't possibly get hold of. Sadly we now have loads of horses being treated with Metformin following this test, when they would almost certainly test normal on a hay-fed resting insulin test - i.e. their day to day life is controlling their insulin.

The in-feed glucose challenge measures how much insulin a horse secretes (and then cannot clear) when it eats a large amount of glucose quickly. It doesn't measure how that horse might respond to its normal diet.

Horses with EMS can have very high insulin results with the in-feed glucose test, over 800 uIU/ml. We know that this insulin level causes laminitic changes in the feet when kept at that level for 6 hours. Whilst the insulin level caused by the test will peak and then fall, the damage caused by exposure to these high levels of insulin for less than 6 hours hasn't been looked at.

The in-feed glucose challenge uses a large amount of glucose (either 1 g or 0.5 g per kg bodyweight, so 500 or 250 g for a 500 kg horse), an amount that a horse could not eat in its natural diet. One problem with this is that glucose enters the blood through glucose transporters, which can become saturated. When a horse is used to having a lot of sugar in its diet, it will increase the number of glucose transporters (this has been proven by feeding increasing amounts of starch). But when a horse is usually on a low sugar diet and is suddenly fed a huge amount of glucose, a large amount of this may be unable to be absorbed in the small intestine and will be carried through to the hind gut. So the number of glucose transporters will have an effect on the insulin result. And the test could potentially cause diarrhoea, gas and colic - we have had reports of diarrhoea following the test using 1g/kg bw glucose.

As can be seen from the paragraph above, this amount of glucose is FAR more than a horse can possibly eat naturally. So although this test has been used in research to distinguish horses with EMS from horses without EMS, all it really tells you is how much insulin your horse will produce if given a massive amount of sugar that it couldn't possibly get hold of. Sadly we now have loads of horses being treated with Metformin following this test, when they would almost certainly test normal on a hay-fed resting insulin test - i.e. their day to day life is controlling their insulin.

The in-feed glucose challenge measures how much insulin a horse secretes (and then cannot clear) when it eats a large amount of glucose quickly. It doesn't measure how that horse might respond to its normal diet.

Horses with EMS can have very high insulin results with the in-feed glucose test, over 800 uIU/ml. We know that this insulin level causes laminitic changes in the feet when kept at that level for 6 hours. Whilst the insulin level caused by the test will peak and then fall, the damage caused by exposure to these high levels of insulin for less than 6 hours hasn't been looked at.

TLS suggestions for diagnostic testing:

If a horse has had laminitis or has any clinical signs of EMS, such as being overweight, having a cresty neck or fat pads, start with a resting insulin test - fasting or low sugar hay is a decision for the owner. If this test is negative, then an oral sugar test will give an idea of that horse's insulin response to sugar. However, a positive OST is not a reason to start treatment with Metformin, it indicates that diet, weight control and exercise should be improved.

If a horse has never had laminitis and has no obvious signs of EMS, but seems the type of horse that might be susceptible, then going straight to the OST seems justified, as a resting insulin would be quite likely to come back negative, and the OST shouldn't raise insulin significantly if the normal diet isn't doing so.

For PPID horses with no signs of EMS and that have never had laminitis, either start with a resting insulin or go straight for the OST. All horses with PPID should have insulin tested. If there really is no suspicion of EMS then going straight to the OST is probably justified. But if there's the slightest suspicion of EMS, it's probably best to start with a resting insulin.

Conclusion:

Resting insulin - best place to start for horses that have had laminitis or are pretty likely to have EMS;

Oral sugar test - best place to start for horses that have never had laminitis and have no obvious signs of EMS.

TLS does not recommend the in-feed glucose challenge.

If a horse has had laminitis or has any clinical signs of EMS, such as being overweight, having a cresty neck or fat pads, start with a resting insulin test - fasting or low sugar hay is a decision for the owner. If this test is negative, then an oral sugar test will give an idea of that horse's insulin response to sugar. However, a positive OST is not a reason to start treatment with Metformin, it indicates that diet, weight control and exercise should be improved.

If a horse has never had laminitis and has no obvious signs of EMS, but seems the type of horse that might be susceptible, then going straight to the OST seems justified, as a resting insulin would be quite likely to come back negative, and the OST shouldn't raise insulin significantly if the normal diet isn't doing so.

For PPID horses with no signs of EMS and that have never had laminitis, either start with a resting insulin or go straight for the OST. All horses with PPID should have insulin tested. If there really is no suspicion of EMS then going straight to the OST is probably justified. But if there's the slightest suspicion of EMS, it's probably best to start with a resting insulin.

Conclusion:

Resting insulin - best place to start for horses that have had laminitis or are pretty likely to have EMS;

Oral sugar test - best place to start for horses that have never had laminitis and have no obvious signs of EMS.

TLS does not recommend the in-feed glucose challenge.

Monitoring

Insulin is tested to diagnose EMS/insulin dysregulation, to assess laminitis risk and potentially to quantify how significant any laminitis risk is likely to be. Following initial diagnosis, insulin should continue to be tested to monitor improvements in insulin regulation, until the horse's insulin levels remain normal on his usual diet.

The factors that cause/contribute to insulin dysregulation/hyperinsulinaemia/insulin resistance can and must be managed or treated so that insulin levels return to normal, or as close to normal as possible. Remember that EMS is not a disease, it is a cluster of risk factors that increase the risk of laminitis, and these risk factors can be reduced, often to the point where the horse is at no greater risk of laminitis than any other horse, as long as it is managed carefully.

Insulin is tested to diagnose EMS/insulin dysregulation, to assess laminitis risk and potentially to quantify how significant any laminitis risk is likely to be. Following initial diagnosis, insulin should continue to be tested to monitor improvements in insulin regulation, until the horse's insulin levels remain normal on his usual diet.

The factors that cause/contribute to insulin dysregulation/hyperinsulinaemia/insulin resistance can and must be managed or treated so that insulin levels return to normal, or as close to normal as possible. Remember that EMS is not a disease, it is a cluster of risk factors that increase the risk of laminitis, and these risk factors can be reduced, often to the point where the horse is at no greater risk of laminitis than any other horse, as long as it is managed carefully.

This might mean:

Overweight horses lose weight until they reach their correct weight.

Levels of sugar and starch in the diet are kept low - generally total NSC or ESC plus starch in the diet should be below 10%; some horses may require diets with lower levels of sugar and starch.

Exercise is introduced/increased if the horse's feet are stable and correctly aligned and supported.

PPID is assessed as a cause of hyperinsulinaemia and treated if present.

Corticosteroid use is avoided or discontinued (under veterinary supervision).

Some horses appear to have a stronger genetic disposition to insulin dysregulation than others - they are likely to need stricter management of the above factors.

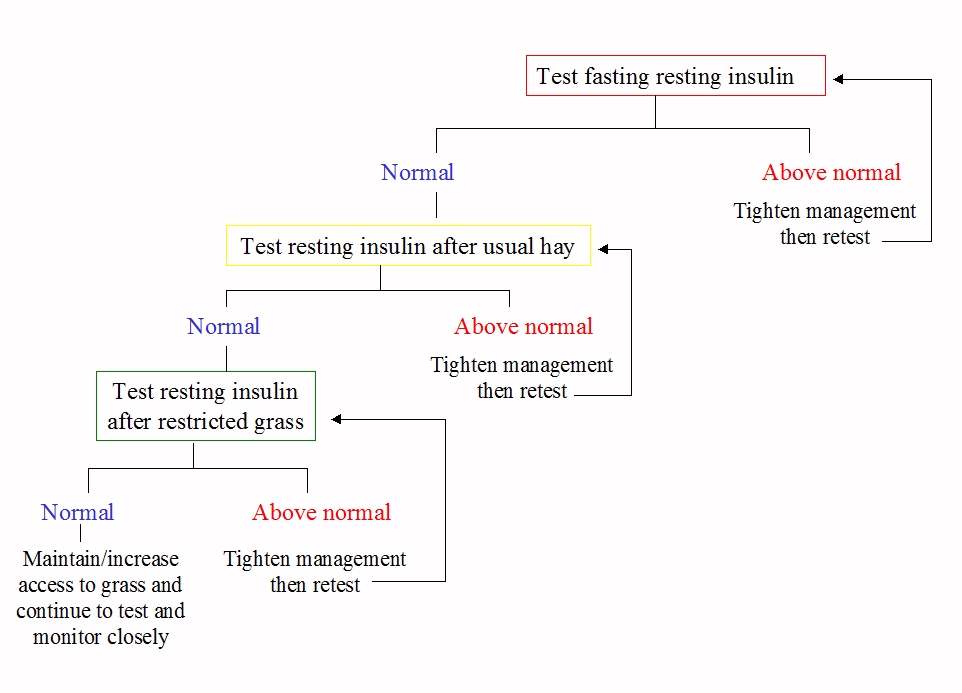

To monitor improvement, it is often suggested that the test that was used for diagnosis be repeated under the same conditions. However, what we probably most need to know is whether the horse has above normal levels of insulin every day when eating its usual diet. If an initial fasting resting insulin was positive, continue to test this under the same test conditions until a normal result is seen. Once fasting resting insulin is normal (or if a non-fasting resting test was the initial test used), next time test resting insulin with the horse eating his normal hay. When that is normal, if you want to return the horse to grazing, test resting insulin with the horse eating a restricted amount of his normal grass. If the grass causes an above normal insulin result, then you know you probably need to restrict grass further or eliminate grazing completely. If you get a normal insulin result after restricted grazing, you can probably continue to allow access to grass, monitoring closely for signs of laminitis/EMS and testing insulin as often as you can. There's no science behind this, but it seems logical.

Overweight horses lose weight until they reach their correct weight.

Levels of sugar and starch in the diet are kept low - generally total NSC or ESC plus starch in the diet should be below 10%; some horses may require diets with lower levels of sugar and starch.

Exercise is introduced/increased if the horse's feet are stable and correctly aligned and supported.

PPID is assessed as a cause of hyperinsulinaemia and treated if present.

Corticosteroid use is avoided or discontinued (under veterinary supervision).

Some horses appear to have a stronger genetic disposition to insulin dysregulation than others - they are likely to need stricter management of the above factors.

To monitor improvement, it is often suggested that the test that was used for diagnosis be repeated under the same conditions. However, what we probably most need to know is whether the horse has above normal levels of insulin every day when eating its usual diet. If an initial fasting resting insulin was positive, continue to test this under the same test conditions until a normal result is seen. Once fasting resting insulin is normal (or if a non-fasting resting test was the initial test used), next time test resting insulin with the horse eating his normal hay. When that is normal, if you want to return the horse to grazing, test resting insulin with the horse eating a restricted amount of his normal grass. If the grass causes an above normal insulin result, then you know you probably need to restrict grass further or eliminate grazing completely. If you get a normal insulin result after restricted grazing, you can probably continue to allow access to grass, monitoring closely for signs of laminitis/EMS and testing insulin as often as you can. There's no science behind this, but it seems logical.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. What is insulin resistance?

A. When a normal horse eats, glucose is absorbed into the blood stream and insulin is released to enable that glucose to enter insulin sensitive tissue – blood levels of both glucose and insulin rise after a meal and then drop back down.

When a horse with insulin resistance eats, glucose is absorbed into the blood stream and insulin is released,

but the insulin sensitive tissue (primarily muscle) does not respond normally to that insulin, which prevents glucose in the blood from entering the tissue normally. The pancreas "compensates" by producing more insulin to ensure that glucose does enter the tissue - blood levels of insulin increase and take longer to drop back down (compensatory hyperinsulinaemia).

Q. What mechanisms can cause high levels of insulin?

A. Insulin can be increased because of:

1. hyperinsulinaemia without insulin resistance - e.g. hormones produced in excess when a horse has PPID may cause excess insulin to be produced, regardless of diet - it is possible that CLIP could be responsible for this - it has been shown to raise insulin in pigs. Chronic hyperinsulinaemia (and hyperglycaemia) are likely to lead to tissue insulin resistance.

2. insulin resistance at the level of the tissue (muscle), leading to compensatory hyperinsulinaemia (see above).

3. reduced clearance of insulin by the liver.

If a horse has greater than normal absorption of glucose or greater than normal release of insulin from the pancreas, over time the horse can develop insulin resistance at the level of the tissue - a dynamic oral test will pick up dysfunction at every level. However, if you only use dynamic and not resting tests, you don't know whether the insulin result after feeding sugar/glucose is due purely to the sugar/glucose, or whether it would have been above normal without the sugar/glucose.

Q. My horse had a positive fasting resting insulin result, and my vet has now suggested carrying out a glucose challenge test - why?

A. A reliable positive fasting resting insulin result should be sufficient for a diagnosis of EMS/insulin dysregulation, together with clinical signs and history. There is no need to carry out a glucose challenge test as well, particularly as a horse with an above normal resting insulin may have a very high insulin response to glucose. Management changes should be made (reduced sugar/starch diet, weight loss, increased exercise if appropriate) and PPID eliminated as a possible cause of the above normal insulin, and resting insulin retested under the same conditions until a normal result is achieved. At this point you might consider carrying out the oral sugar test, to see whether the horse still has an abnormal insulin response to sugar, or testing resting insulin when the horse is eating his normal diet, as above.

Q. What is insulin resistance?

A. When a normal horse eats, glucose is absorbed into the blood stream and insulin is released to enable that glucose to enter insulin sensitive tissue – blood levels of both glucose and insulin rise after a meal and then drop back down.

When a horse with insulin resistance eats, glucose is absorbed into the blood stream and insulin is released,

but the insulin sensitive tissue (primarily muscle) does not respond normally to that insulin, which prevents glucose in the blood from entering the tissue normally. The pancreas "compensates" by producing more insulin to ensure that glucose does enter the tissue - blood levels of insulin increase and take longer to drop back down (compensatory hyperinsulinaemia).

Q. What mechanisms can cause high levels of insulin?

A. Insulin can be increased because of:

1. hyperinsulinaemia without insulin resistance - e.g. hormones produced in excess when a horse has PPID may cause excess insulin to be produced, regardless of diet - it is possible that CLIP could be responsible for this - it has been shown to raise insulin in pigs. Chronic hyperinsulinaemia (and hyperglycaemia) are likely to lead to tissue insulin resistance.

2. insulin resistance at the level of the tissue (muscle), leading to compensatory hyperinsulinaemia (see above).

3. reduced clearance of insulin by the liver.

If a horse has greater than normal absorption of glucose or greater than normal release of insulin from the pancreas, over time the horse can develop insulin resistance at the level of the tissue - a dynamic oral test will pick up dysfunction at every level. However, if you only use dynamic and not resting tests, you don't know whether the insulin result after feeding sugar/glucose is due purely to the sugar/glucose, or whether it would have been above normal without the sugar/glucose.

Q. My horse had a positive fasting resting insulin result, and my vet has now suggested carrying out a glucose challenge test - why?

A. A reliable positive fasting resting insulin result should be sufficient for a diagnosis of EMS/insulin dysregulation, together with clinical signs and history. There is no need to carry out a glucose challenge test as well, particularly as a horse with an above normal resting insulin may have a very high insulin response to glucose. Management changes should be made (reduced sugar/starch diet, weight loss, increased exercise if appropriate) and PPID eliminated as a possible cause of the above normal insulin, and resting insulin retested under the same conditions until a normal result is achieved. At this point you might consider carrying out the oral sugar test, to see whether the horse still has an abnormal insulin response to sugar, or testing resting insulin when the horse is eating his normal diet, as above.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed