| We're often asked which supplements we would recommend for a horse with laminitis, or whether the latest heavily marketed nutraceutical will be the miracle cure for the fat pony that "just won't lose weight". There's a simple answer. None! There are no magic potions, no silver bullets. If there was peer-reviewed scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of a supplement that prevented or cured laminitis, you can be pretty certain you'd have heard of it and we'd all be using it! |

Owners often search for a "natural" remedy to EMS or PPID, rather than use licensed (and therefore tried and tested) medication. However, rather worryingly, in-feed supplements can be legally sold without evidence of effectiveness or even safety. If companies are happy to make a profit from these products then surely they should also be happy to fund clinical trials to prove that they do what they claim, and that they are safe.

And just because something is "natural", that doesn't mean it is better, or safer. You're aware of ragwort poisoning! And you may know that organic sources of selenium, whilst better absorbed than inorganic sources, have a much smaller margin of safety.

It can be challenging to identify the ingredients in a supplement beyond "blend of plant extracts" or "range of compounds" - would you really feel happy feeding something to your horse without knowing what was in it - particularly now you know nutraceuticals can be sold without evidence of safety? Sometimes all we're given is a list of botanical names of herbs, which is great for clarity, but they generally all have common names - why can't we have those too to save us time looking them up? Some supplements targeted at laminitics list dextrose (that's glucose) as their greatest ingredient - not a good start for keeping blood glucose levels low and avoiding increased insulin!

Vague descriptions and claims are often used, such as "powerful ingredients", "work to support", "rebalances digestion", "highly effective". Hmm, says who - where are the results of clinical trials to prove this? Some companies might suggest that their product has a clinical effect, such as lowering insulin, and perhaps it does. However, insulin levels are likely to be higher in an actively laminitic horse than one well on the way to recovery. For example, take an overweight pony who has been eating unlimited grass (high sugar) and developed laminitis due to EMS, he's in pain, he's got some rotation, his feet haven't yet been realigned and supported. His blood tests are likely to show above normal concentrations of insulin, and possibly also cortisol, if tested, due to the pain (cortisol and insulin are increased by pain) and uncontrolled insulin resistance. Take the pony off the grass and feed him the correct amount of < 10% ESC + starch hay to provide adequate energy for gradual weight loss, supplement his diet to ensure correct levels of protein, minerals, vitamins and essential fatty acids, and ensure his feet are realigned, correctly balanced and well supported, so that he is no longer in pain. Blood tested a month or more later will very likely show significantly lower levels of insulin (and cortisol - there is no reason to test cortisol, it has no diagnostic value for EMS or PPID, but may indicate pain). With removal of pain and correct management for insulin resistance, it is normal for insulin concentrations to reduce - therefore any claim that a supplement does this should be supported by clinical trials using reasonable numbers of horses, with one group receiving the supplement, the other group receiving no supplement, and everything else identical between the groups.

Many laminitis supplements certainly sound pretty amazing, claiming to normalize glucose and insulin levels, reduce fat deposits, eliminate soreness in feet, normalize hoof growth, allow horses to eat high sugar grass - why are we worrying about laminitis, ensuring our horses eat low sugar diets, getting their feet trimmed every couple of weeks, when such miracle cures exist?! Unfortunately such claims are rarely accompanied by any explanation as to how the product might achieve these results. Now that we've identified three quite distinct types of laminitis - sepsis-associated, endocrine and supporting limb - which require different treatment and prevention, it seems odd that most laminitis supplements continue to target simply "laminitis". Indeed, some marketing information appears quite confused, with references to toxins produced by bacteria entering the blood in response to eating grass - by toxins/bacteria it presumably refers to acidosis which can cause a sepsis-associated laminitis, but pasture associated laminitis is now thought to cause an endocrine laminitis - not the same thing at all. Other marketing suggests the blood supply to the feet is restricted - but Melody de Laat's 2011 research suggested that vasodilation is likely with hyperinsulinaemia-induced laminitis. If the manufacturer of a supplement doesn't understand how laminitis works, how likely is it that their product works?

Other supplements contain nutrients that are considered important for laminitics, such as anti-oxidants, minerals, amino acids - and they may well be, but ALL horses should have a correctly balanced diet based on analysed forage with protein, minerals, vitamins and essential fatty acids supplemented in the correct ratios to ensure above minimum requirements are met, according to the horse's work load and stage of life (e.g. breeding, growing) - this is "feed", not "supplement". Supplementation of specific minerals such as magnesium and chromium is often suggested for horses with laminitis, and whilst there is anecdotal evidence that supplementing magnesium has helped reduce cresty necks and fat deposits, research hasn't found evidence of this, and it is likely that supplementation only or mostly helps when a deficiency exists in the first place.

The one thing that supplements for laminitis usually have in common is a large price!

So what can you do to help your laminitic horse?

Well, sorting out laminitis is generally pretty simple, and you'll see this repeated over and over again on The Laminitis Site:

1. Diagnose and remove/treat the cause.

Most laminitis (~90%) is endocrinopathic, but you need to know whether it is EMS or PPID - both have laminitis caused by insulin dysregulation, the difference is that EMS can usually be controlled simply by a low sugar/starch diet, weight loss if necessary and exercise when able, whereas PPID is an ongoing degenerative disease that requires pergolide, usually for life, with similar management to EMS if insulin dysregulation is involved. The diet should be perfect - analysed hay to provide enough energy for ideal bodyweight, with all essential nutrients (protein, minerals, vitamins, essential fatty acids) balanced to it, taking account of ratios between minerals.

And just because something is "natural", that doesn't mean it is better, or safer. You're aware of ragwort poisoning! And you may know that organic sources of selenium, whilst better absorbed than inorganic sources, have a much smaller margin of safety.

It can be challenging to identify the ingredients in a supplement beyond "blend of plant extracts" or "range of compounds" - would you really feel happy feeding something to your horse without knowing what was in it - particularly now you know nutraceuticals can be sold without evidence of safety? Sometimes all we're given is a list of botanical names of herbs, which is great for clarity, but they generally all have common names - why can't we have those too to save us time looking them up? Some supplements targeted at laminitics list dextrose (that's glucose) as their greatest ingredient - not a good start for keeping blood glucose levels low and avoiding increased insulin!

Vague descriptions and claims are often used, such as "powerful ingredients", "work to support", "rebalances digestion", "highly effective". Hmm, says who - where are the results of clinical trials to prove this? Some companies might suggest that their product has a clinical effect, such as lowering insulin, and perhaps it does. However, insulin levels are likely to be higher in an actively laminitic horse than one well on the way to recovery. For example, take an overweight pony who has been eating unlimited grass (high sugar) and developed laminitis due to EMS, he's in pain, he's got some rotation, his feet haven't yet been realigned and supported. His blood tests are likely to show above normal concentrations of insulin, and possibly also cortisol, if tested, due to the pain (cortisol and insulin are increased by pain) and uncontrolled insulin resistance. Take the pony off the grass and feed him the correct amount of < 10% ESC + starch hay to provide adequate energy for gradual weight loss, supplement his diet to ensure correct levels of protein, minerals, vitamins and essential fatty acids, and ensure his feet are realigned, correctly balanced and well supported, so that he is no longer in pain. Blood tested a month or more later will very likely show significantly lower levels of insulin (and cortisol - there is no reason to test cortisol, it has no diagnostic value for EMS or PPID, but may indicate pain). With removal of pain and correct management for insulin resistance, it is normal for insulin concentrations to reduce - therefore any claim that a supplement does this should be supported by clinical trials using reasonable numbers of horses, with one group receiving the supplement, the other group receiving no supplement, and everything else identical between the groups.

Many laminitis supplements certainly sound pretty amazing, claiming to normalize glucose and insulin levels, reduce fat deposits, eliminate soreness in feet, normalize hoof growth, allow horses to eat high sugar grass - why are we worrying about laminitis, ensuring our horses eat low sugar diets, getting their feet trimmed every couple of weeks, when such miracle cures exist?! Unfortunately such claims are rarely accompanied by any explanation as to how the product might achieve these results. Now that we've identified three quite distinct types of laminitis - sepsis-associated, endocrine and supporting limb - which require different treatment and prevention, it seems odd that most laminitis supplements continue to target simply "laminitis". Indeed, some marketing information appears quite confused, with references to toxins produced by bacteria entering the blood in response to eating grass - by toxins/bacteria it presumably refers to acidosis which can cause a sepsis-associated laminitis, but pasture associated laminitis is now thought to cause an endocrine laminitis - not the same thing at all. Other marketing suggests the blood supply to the feet is restricted - but Melody de Laat's 2011 research suggested that vasodilation is likely with hyperinsulinaemia-induced laminitis. If the manufacturer of a supplement doesn't understand how laminitis works, how likely is it that their product works?

Other supplements contain nutrients that are considered important for laminitics, such as anti-oxidants, minerals, amino acids - and they may well be, but ALL horses should have a correctly balanced diet based on analysed forage with protein, minerals, vitamins and essential fatty acids supplemented in the correct ratios to ensure above minimum requirements are met, according to the horse's work load and stage of life (e.g. breeding, growing) - this is "feed", not "supplement". Supplementation of specific minerals such as magnesium and chromium is often suggested for horses with laminitis, and whilst there is anecdotal evidence that supplementing magnesium has helped reduce cresty necks and fat deposits, research hasn't found evidence of this, and it is likely that supplementation only or mostly helps when a deficiency exists in the first place.

The one thing that supplements for laminitis usually have in common is a large price!

So what can you do to help your laminitic horse?

Well, sorting out laminitis is generally pretty simple, and you'll see this repeated over and over again on The Laminitis Site:

1. Diagnose and remove/treat the cause.

Most laminitis (~90%) is endocrinopathic, but you need to know whether it is EMS or PPID - both have laminitis caused by insulin dysregulation, the difference is that EMS can usually be controlled simply by a low sugar/starch diet, weight loss if necessary and exercise when able, whereas PPID is an ongoing degenerative disease that requires pergolide, usually for life, with similar management to EMS if insulin dysregulation is involved. The diet should be perfect - analysed hay to provide enough energy for ideal bodyweight, with all essential nutrients (protein, minerals, vitamins, essential fatty acids) balanced to it, taking account of ratios between minerals.

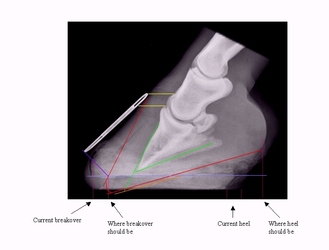

| 2. Support and realign the feet. The back of the foot - the frog, heels, bars - are not greatly affected by laminitis, so this is where the horse needs to be able to support its weight. The frog should always be weightbearing, the heels should be back in line with the widest part of the frog, and either padding or deep supportive bedding used. X-rays should be taken as soon as possible, and any rotation realigned immediately by bringing the palmar angle back to (generally) no more than 5 degrees and the feet kept perfectly aligned - see Feet. In our experience, most horses fail to recover from laminitis because their feet are not correctly realigned and supported, or to a lesser extent because the cause of their laminitis is not correctly diagnosed and removed/treated. |

It takes a lot more effort to put these management changes in place than to simply add a supplement to a horse's feed - but the difference is, these management changes consistently work!

See also: Are you using illegal supplements?

See also: Are you using illegal supplements?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed