|

Danica Pollard from the Animal Health Trust and CARE About Laminitis talks about Laminitis in the Autumn with NKC Equestrian Training on 04 October 2019.

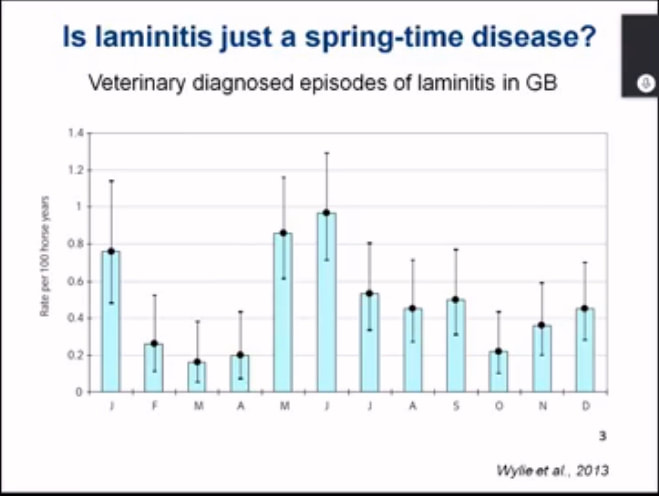

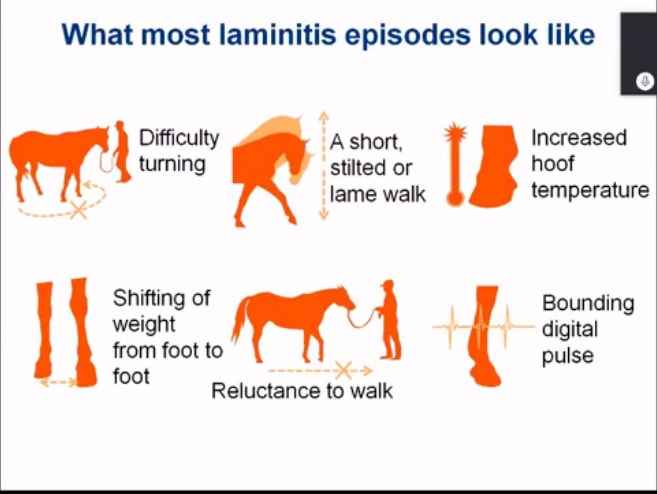

Notes: Laminitis can happen at any time of year, not just in the spring. Ideally we want to prevent laminitis, but if it does happen we need to identify and treat laminitis as early as possible. Signs of laminitis include: Difficulty turning. A short, stilted or pottery stride, being "footy", often worse on hard ground than soft. Reluctance to walk. Warmer than normal hoof wall or coronary band. Digital pulse more "bounding" than normal at rest. Shifting weight between affected feet, often called "paddling". Rocked back stance, taking weight on heels. Although 1 foot can be affected, laminitis is far more commonly seen in both front feet or all 4 feet. Always call your vet if you suspect laminitis.

Reasons laminitis might occur in the autumn include:

Seasonal changes in hormones - horses have a seasonal rise in hormones [that increase insulin resistance, thought to help horses prepare for winter food shortages]. Autumn flush of grass as wet and warm weather encourage growth. Owners often increase feed but may reduce exercise as days become shorter/weather less pleasant. Rugging may reduce calories used keeping warm. |

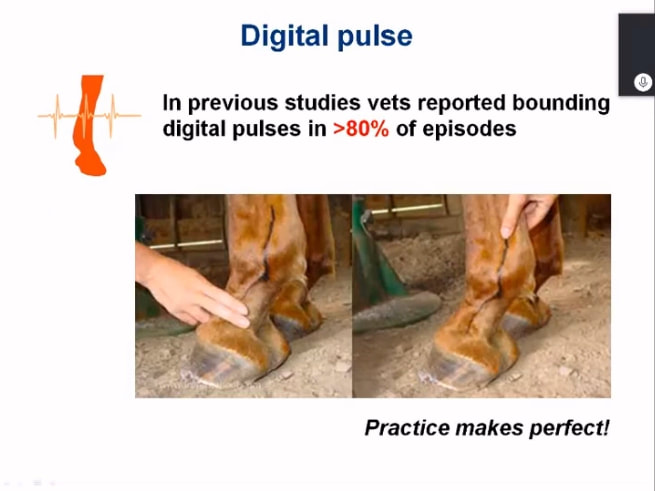

The digital pulse (of the digital artery) can be taken at the fetlock or pastern, on both the inside and outside of the leg. You should know how to do this and what is normal for your horse. Ask your vet to show you. [Mark the best spot to check the pulse on your horse's leg with a marker pen, and] practise until you can confidently check the pulse. |

Monitor your horse's body condition score (BCS) by getting hands on to feel for fat deposits. More information here: Body condition scoring.

Monitor weight - with a weighbridge, weight tape, a length of string or girth holes - if the girth isn't going as tight or weight increases on a horse in good condition, take action to get the horse to lose weight straight away.

Ask your vet, farrier, physio to help you assess your horse's body condition.

Assess how much grass or forage your horse is eating. Dung production can help monitor intake - more dung usually means more food eaten. Watch how much time your horse has his head down eating grass - a field may look bare, but if a horse is busy eating, he is finding grass! Fence off a small area of field so that your horse can't graze it and watch how much grass grows - you may think your horse's field is bare until you see how much grass grows when he isn't eating it.

For weight loss, control intake by using slow feeder techniques, prolonging chewing time, and aiming to feed less calories without reducing the amount fed, and increase exercise.

Horses with PPID may be particularly at risk from autumn laminitis.

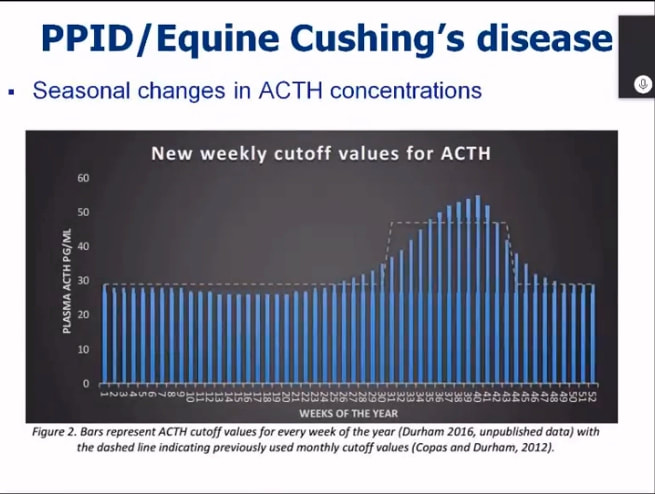

PPID (formerly called Equine Cushing's disease) is a progressive degenerative disease that becomes more common with age (one study found PPID in 21% of horses older than 15). PPID has been diagnosed in horses younger than 15 [but the Equine Endocrine Pioneers Circle suggested in 2019 that PPID in a horse younger than 10 is "very unlikely"]. In horses with PPID, degeneration of neurons [in the hypothalamus in the brain] causes incorrect messages to be sent to the pituitary gland, resulting in increased levels of certain hormones, including ACTH, which is the hormone most commonly tested to diagnose and monitor PPID.

Clinical signs of PPID include changes to the coat and delayed shedding of the winter coat, lethargy, muscle loss along the topline, pot belly, abnormal fat deposits e.g. cresty neck and filled supraorbital hollows above the eyes, increased drinking and urination, lowered immunity so increased infections, and laminitis.

Not all horses with PPID are at greater risk of laminitis - it is horses with PPID and insulin dysregulation that are at risk of laminitis, so insulin should be tested as well as ACTH if PPID is suspected to assess laminitis risk.

The treatment for PPID is Prascend (pergolide).

[Does treatment with pergolide stop/slow progression of PPID? There has been suggestion that pergolide may reduce the hyperplasia and hypertrophy (increase in number of and size of cells) caused by the excess production of hormones from the pituitary gland, pergolide has been shown to have neuro-protective properties in other species, and Andy Durham from Liphook Equine Hospital has suggested that if PPID is well controlled and hyperplastic activity suppressed, the dose of pergolide may be able to be reduced – there may be one dose for getting PPID under control and then a lower maintenance dose (Source: "A discussion of Equine Cushing’s disease by Andy Durham and Victoria South November 2017). The Laminitis Site sees many horses with PPID that are able to remain on a low dose for many years, suggesting that progression of the disease is controlled by treatment.]

[Does treatment with pergolide reduce laminitis risk in horses with PPID? Pergolide reduces or controls the excess hormone production. If a horse's insulin dysregulation (ID) is driven by the excess PPID hormones, and treatment reduces/controls these hormones, then it should follow that laminitis risk is reduced. However, if ID is driven at least partly by EMS factors (being overweight, a diet too high in sugar/starch, insufficient exercise), then those factors must be controlled by management.]

|

The best time to diagnose PPID is in the autumn, during the seasonal rise, which peaks August to October (in the northern hemisphere). Although all horses have an increase in ACTH during the seasonal rise, horses with PPID have been shown to have a greater increase, making the difference between horses with PPID and normal horses greater during the seasonal rise. Seasonally adjusted cut-offs are used, although there will always be a grey zone around cut#off figures [and other factors that influence ACTH e.g. stress], and clinical signs must be considered alongside blood test results. ACTH can be tested and PPID diagnosed throughout the year. If you are concerned your horse might have PPID, talk to your vet.

|

Summary:

Laminitis can occur at any time of year - be vigilant all year round.

Autumn laminitis may occur due to seasonal rise hormones, increased grass growth and changes in management such as increasing feed, reducing exercise and rugging unnecessarily. Monitor weight/body condition throughout the year and take action to prevent unwanted weight gain.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed